A myth is haunting the English-speaking world: Germany allegedly shows that emissions rise because renewables can’t replace nuclear – and that France is right to stick with nuclear. What do the data show? Craig Morris reports

Germany reduced emissions while phasing out nuclear power (Public Domain)

It’s not just trolls: Cambridge professors are saying it, and top US journalists are saying it, and a US presidential candidate told it to the New York Times:

“Germany initially set out to close all of its nuclear reactors by 2022, but as a result, they are now likely to miss their emissions reduction targets. And France is now considering options to extend the life of many of its older nuclear power plants.”

— US presidential candidate Marianne Williamson in the New York Times

What’s worse, US policymakers are saying it. Five US states now subsidize nuclear to keep reactors from closing, and it’s possible that all of them have done so based on this incorrect assumption. It happened years ago in New York State with explicit reference to German emissions allegedly rising because of the phase-out, it then happened in Illinois, and as one press report from Ohio put it this year when the new nuclear subsidy was announced:

The experience of Germany was repeatedly used as an example of what might happen in Ohio. Germany decommissioned its nuclear plants in favor of an all-renewable strategy. Electricity prices spiked and carbon pollution spiked, in part because of the ramping up of fossil-fuel plants to compensate for when wind and solar faltered.

“If the studies are correct, the Germans must not know how to do this,” Mr. Randazzo [chairman of the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio] said.

“If the studies are correct” indeed: So do Germany and France show that climate change requires nuclear, as Williamson says? Let’s start with France.

France’s “nuclear options”

The French government has an official policy to reduce the share of nuclear in the power sector from around 75% to 50%. The original deadline was postponed in 2017 from 2025 to 2035 after years of inaction during the Hollande government, which adopted the policy in 2012. To complicate matters, some in the French government want new reactors; on Oct 15, the government asked reactor builder EDF to construct another six of the units it has never completed in the next 15 years.

But last spring, Williamson could not have been referring to yesterday’s announcement. In speaking of a French plan to extend reactor lives, Williamson may have been talking about the Grand Carénage – or “grand overhaul” – of French reactors. The carénage is not “France’s” plan, however, but EDF’s; the power company that operates the reactors wishes to extend their service lives to sixty years rather than close them. It cannot do so, however, without permission from the ASN, the French nuclear security agency commonly called a “watchdog.”

Here, we see how hard it is to say what “France” – a pluralistic country – wants. The French government owns 84% of EDF, which wants longer reactor lives. The ASN, a government regulator, might not allow those extensions: when it discovered flawed workmanship in steel containment vessels in a slew of old reactors, it temporarily closed a third of France’s reactors for unplanned safety inspections in 2016. (Flawed workmanship also affects the new EPRs, by the way.)

There are no details to the overhaul or the nuclear reduction: no list of reactors for EDF’s (not France’s!) carénage, no dedicated website, nor any roadmap of which reactors would go offline when towards the reduction to 50% nuclear power.

But reality marches on while policies remain vague. Until recently, it was generally understood that France’s oldest two reactors in Fessenheim would not be closed until the new one in Flamanville went online, though even that tradeoff was uncertain. Now, the ASN has postponed the opening of Flamanville for another three years – but EDF has given up on Fessenheim. In September, the firm announced it would close the two reactors by mid-2020. France is thus slipping into an unplanned nuclear phaseout.

This lack of detailed planning is French policymaking-as-usual, at least for energy: President Hollande invented the 50% target during the 2012 election campaign in the wake of the Fukushima accident based on no research. When the policy was adopted, it finally brought about the research it should have been based on. Researchers found that the policy might raise emissions in the interim. By postponing the date to 2035, however, they have merely kicked the can down the road; there are no better ideas today than there were in 2017, when the postponement was announced.

Doesn’t that prove Williamson’s point: closing nuclear raises emissions? No, France’s concern is theoretical: they didn’t actually close any reactors and try to replace the power with renewables. Rather, the French left nuclear on, and renewables hardly grew; solar (1.9%) and wind (5.1%) made up a mere 7.5% of French power supply in 2018. (In Germany, solar alone covered 7.7% of demand in 2018, with wind adding another 18.7% for a total of 26.4%). But in Germany, replacing nuclear with renewables isn’t just a postponed political ambition; it’s happening. So what do we know?

Germany emissions during the nuclear phaseout

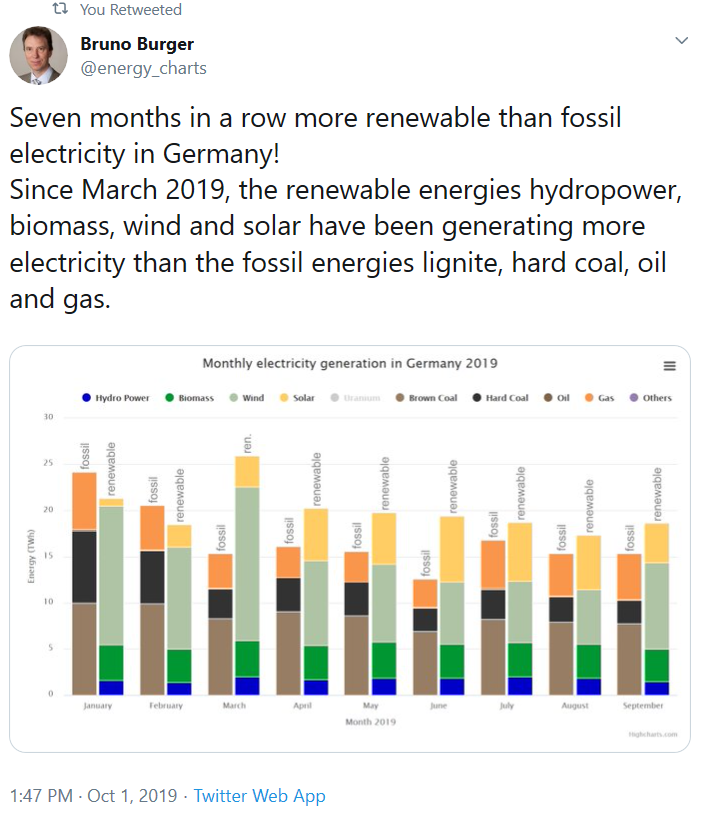

In 2011, eight of Germany’s 17 reactors were closed. From 2010-2017, emissions in the power sector fell by more than 15%. For 2018, the power sector numbers are not yet in, but emissions from the energy sector fell by nearly two percentage points. And to date in 2019, renewables have nearly reached 50% of power supply. Germany now has some 210 TWh of non-hydro renewable power, far more than the record level of 171 TWh in 2001 for nuclear. Since 2010, renewable power has grown nearly twice as fast as nuclear shrank. Some nine tenths of it is wind and solar alone. Clearly, Germany shows that renewables can reduce emissions during a nuclear phaseout.

(Bruno Burger, Twitter @energy_charts)

At this point, I hear objections. The first: “but Germany is going to miss its 2020 climate target!” Yes, it is expected to reach a 32% emissions reduction, not 40% relative to 1990 (French emissions fell by 15% from 1990-2017 in comparison, albeit from a much lower level thanks to nuclear). But the Germans don’t see the power sector as the main problem. As Deutsche Bank recently put it, “So far, Germany’s efforts… have focused on the electricity sector. However, attention is increasingly shifting towards the transport sector and its steadily rising carbon emissions.” Former Environmental Minister and Christian Democrat Klaus Töpfer recently worded the German consensus well: “We have the highest taxes on electricity although we have reduced emissions there the most.” That’s right: Germany has performed best in the sector where it has removed nuclear and worse in sectors where nuclear plays little or no role: mobility, agriculture, and heat.

The second objection is generally: “Germany would have lowered emissions even more if it had phased out coal, not nuclear.” That’s a fine thing to discuss, but it only moves us from a falsehood (“German phaseout raised emissions”) to revisionist history – not to facts. The revisionist historians act as though renewables would have been built anyway if nuclear remained online. As I wrote in my 50-page paper entitled Can reactors react (2018), the Germans argued a decade ago that renewables were unlikely to be built if nuclear stayed online.

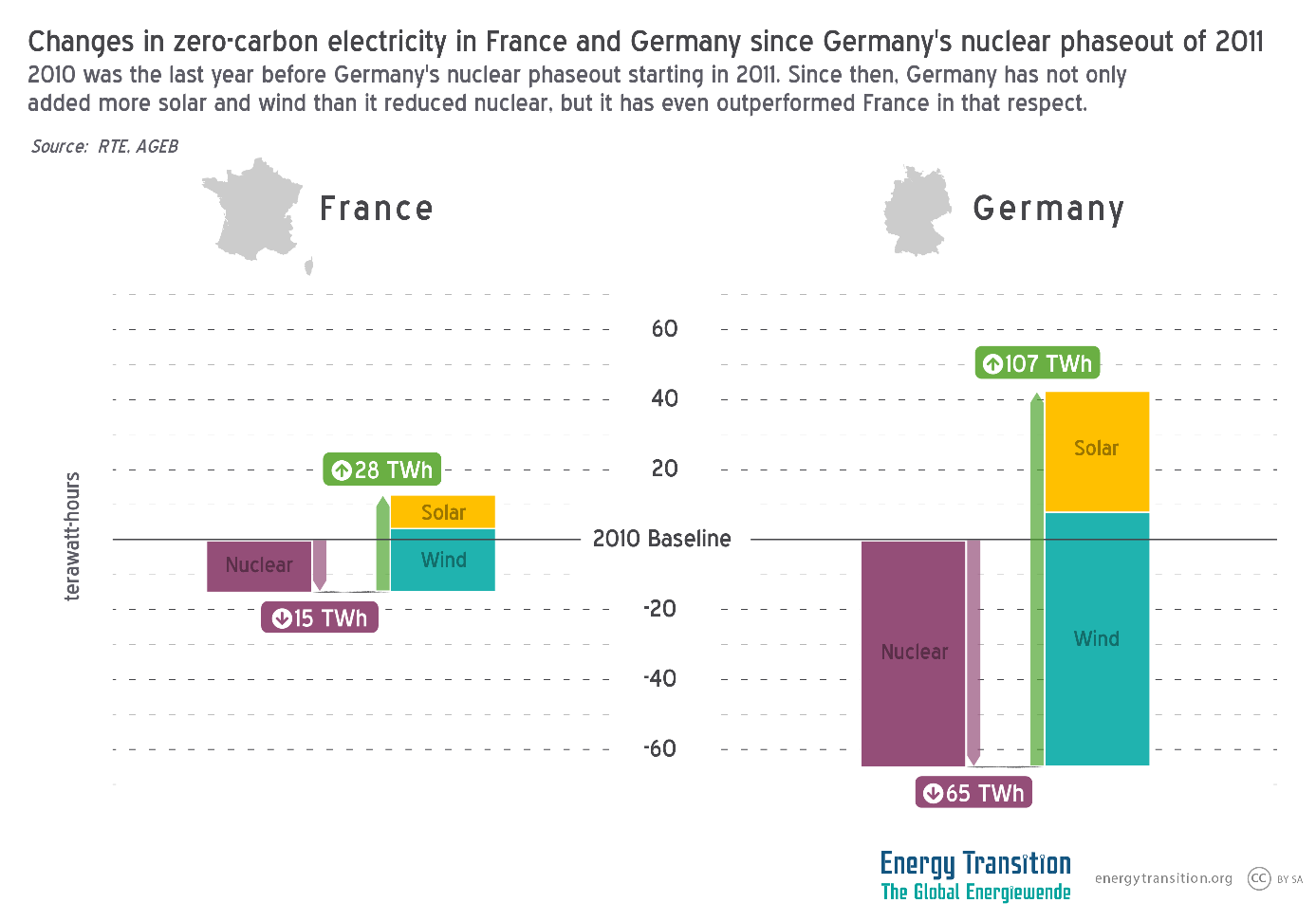

What do the French and German cases show about how much renewable energy gets added when nuclear stays online? The French are also failing to add new nuclear as quickly as its own power company closes old reactors it wishes to keep on. From 2010-2018, wind and solar grew by 27.4 TWh in France, while nuclear shrank by 14.7 TWh (and demand stayed flat). During the same timeframe in Germany, nuclear shrank by 64.6 TWh – but solar and wind alone grew by 91.8 TWh.

The current French situation suggests that, if you remain committed to nuclear, nuclear power nonetheless shrinks; to make matters worse, the growth of renewables struggles to close the gap. Germany suggests that, if you stick with renewables and phase out nuclear, renewables growth outstrips the drop in nuclear nearly twofold, and you reduce emissions by 2 percentage points annually in the power sector.

No limit to the mental contortions by anti-nuclear hacks to try and argue obviously false points. It’s simple. Imagine if Germany had used renewables to replace coal instead of nuclear. Emissions would be much lower. Given the seriousness of global warming (not to mention the health impacts of air pollution), closing nuclear plants instead of (or before) coal plants is morally indefensible. That renewables should be used to replace fossil fuels, instead of nuclear, should not be at all controversial or hard to understand.

I can’t even understand the bizarre statement that if you remain committed to nuclear, nuclear shrinks anyway. I suppose I have a different definition of “committed”. France may reduce nuclear because of a (indefensible) *political* decision to mandate its reduction (to 50%), Hardly meets the definition of “committed”. Instead, it’s just more anti-nuclear political BS.

Once again, for the remedial class. Shutting down massive generators of carbon free power does not cause emissions to go down! It causes them to go up. New renewable generation (and the massive amount of money required to build it) should actually be used to decarbonize, i.e., replace fossil fuels!

Articles like this are a sign of just how delusional people in Germany and elsewhere have gotten, in their religious anti-nuclear zeal.

Some are concerned about greenhouse gas emissions, according to the first chart in this article, Germany emits about 400+grams CO2 per kilowatt-hour, averaged on an annual basis. When can we expect Germany to be averaging less than 100 grams of CO2 emitted per kilowatt-hour, on an annual basis? https://www.carbonbrief.org/guest-post-ten-charts-show-how-the-world-is-progressing-on-clean-energy

Good for Craig. The whole criticism is pure alternative unicorn history. It would have been nice if Germany had built the same renewables while slowing the nuclear phaseout and cutting coal instead. But this was never politically feasible. The base of the German Green movement and precondition for its relative political success, including the EEG, was widespread post-Chernobyl opposition to nuclear power. Since the rest of the world got the learning-curve benefit of the large German early-stage subsidies for wind and solar – cumulatively over €100 bn IIRC – the least we can do is stop complaining.

Thanks for this one!

The French atom circus faces another record year:

https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/electric-power/112219-infographic-french-nuclear-shutters-through-q4

The big overhaul might not happen at all:

https://www.montelnews.com/fr/story/lirsn-met-en-doute-la-prolongation-de-vie-de-30-racteurs/1059597

(use the translation engine)

The knackers are simply to old:

https://www.montelnews.com/fr/story/l%C3%A2ge-des-cuves-est-une-menace-pour-les-racteurs–experts-/1062280

European power emissions are going down despite plenty of atom power plants closing for good:

https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-global-coal-power-set-for-record-fall-in-2019

(note the missing data for Europe for atom power generation in the chart ” Renewables, gas and falling demand all contributed to the decline in OECD coal use “)

re. carbon emission target of Germany see the latest Ageb report

https://www.ag-energiebilanzen.de/

Nr. 7, 2019 (29. Oktober)

Prognose: Energieverbrauch sinkt weiter

” Da der Verbrauch an Kohlen besonders stark rückläufig war und die erneuerbaren Energien weiter zulegen konnten, geht die AG Energiebilanzen von einem merklichen Rückgang bei den CO2-Emissionen aus. ”

There have been several voices in the last few month pointing out that the emission target 2020 can still be reached. Despite the boycott of the German mafia.

On Friday – with the F4F marches – the Ende-Gelaende week starts, this time in the East:

https://www.ende-gelaende.org/en/lusatia-action-2019/

All out,solidarity!

Very good and useful article, thanks! I’ll probably refer to it the next time I see the fictional narrative of growing CO2 emissions from power production in Germany presented somewhere again.

Germany’s missing the 2020 target, as you pointed out was not only about generation of electricity. They missed the target for reduction in emissions by transportation AND they missed the target for the improvement in energy efficiency, reduction in energy use in buildings. Part of missing the building efficiency improvement was related to split incentives and old buildings (50’s) that would require considerable rethinking to reduce the energy consumption while maintaining or improving the indoor environmental air quality.

Yes, Passivhaus works for new buildings, and Passivhaus retrofits can indeed work for existing buildings, but only if doing so is a high enough priority to fund and roll out nationwide. That still seems to be lagging.

Over the years, one of the simple energy use items I’ve tracked world wide was “lighting” In the US you look at the lightbulbs on the shelves of the home improvement stores or places like Best Buy or Ikea. In Germany it’s easy to compare the equivalent with Saturn and Ikea – against the US counter parts. In 2012 it was uncommon to find LED lightbulbs in the German stores, CFL’s were there but not common, instead the market was for halogen lights. In the US by 2012 the transition to LED’s was well underway, and by 2016 the US IKEA had switched entirely to LED’s, most of the other home improvement stores were switching (or had switched), and the price for a 60W equivalent bulb was roughly $1.40US. When I checked German IKEA and Saturn stores in 2016, the transition to LED’s was in place and underway.

Lighting needs consume a large portion of a building energy use. Halogens save about 20% of the energy over an incandescent, where as an LED can save as much as 90%. Life expectancy for halogen and LED bulbs are about the same… unfortunately that may have locked in that higher energy consumption for lighting in Germany for about seven or eight years. That has effectively slowed the efficiency improvements and resulted in a higher electrical consumption over the years. The higher electrical consumption means the old thermal plants were still being used to offset loads.

The 20 20 20 by 2020 goals need the efficiency goals to be met and exceeded if they were to meet the CO2 reduction goals.

Hello! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you if that

would be okay. I’m undoubtedly enjoying your blog and look forward to new posts.

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but your

sites really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your

website to come back later on. Many thanks