All too often, discussions on sustainability focus on the end products, overlooking the supply chain. A recent IEA report underlined the need for sustainability criteria for minerals used in renewable energies. Bernadinus Steni has the details. This blog post sheds light on manganese mining as second part of our South East Asia Series.

Manganese mining, potentially used for future renewable energy, has a huge environmental impact and violates human rights. (Photo by James St. John, CC BY 2.0)

In Indonesia, ensuring sustainability from the beginning of the supply chain is crucial considering the historical social conflict triggered by mining. Nickel mining in Southeast Sulawesi Province that is currently proposed to be the main sources for RE’s critical materials has seen more than 50 years of social conflict. Hence, social and environmental safeguards essential, not only for the sake of clean energy targets but most importantly, as Amartya Sen said, to secure human dignity. This is especially urgent in the light of Indonesia’s investment policies which tend towards a relaxation for environmental standards to boost economic growth.

A recent report by Herr et al., (2021) claimed that manganese (Mn) is the potential substitutive substance for iridium and ruthenium, which are key elements for luminescent materials and catalysts for converting sunlight into other forms of energy. It has an abundant stock in the earth’s crust, about 900,000 times more than iridium. This finding has triggered more researches about the potential use of Mn for future renewable energy.

However, another recent report on manganese mining operations in South Africa raised concern about the reality of manganese mining. Triggered by the market demand of ending products of manganese including renewable energy, miners in the country operated in poor standards, leading to human rights abuses and environmental damage. Furthermore, Dlamini et al., (2020) assessed 187 black South African manganese mine workers and found that parkinsonian indications were common and associated with estimated manganese exposure and poor quality of life.

My report published online by the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung office in Thailand outlines how mining manganese has posed a dilemma for renewable energy technology. It is also linked to its historical reputation for social conflict. This research case centers on the indigenous peoples in Manggarai of East Nusa Tenggara Province Indonesia where manganese has been mined rampantly operated. Opposition from indigenous groups and local activists has been substantial since the initial operation of the mines since 2004, who argue it contravenes land rights and access to water.

Manganese Mining in Manggarai

Fig. 1. Source: BIG (Indonesian Geospatial Agency)

Manggarai Regency is located on Flores Island, East Nusa Tenggara Province (Fig. 1). Some of the area are semi-arid areas that have rainfall below 1,000 mm/year. Therefore, water access is very a critical topic for the area. Currently, the provincial performance index of the area for the SDG of access to water is one of the lowest (second last) compared to other provinces.

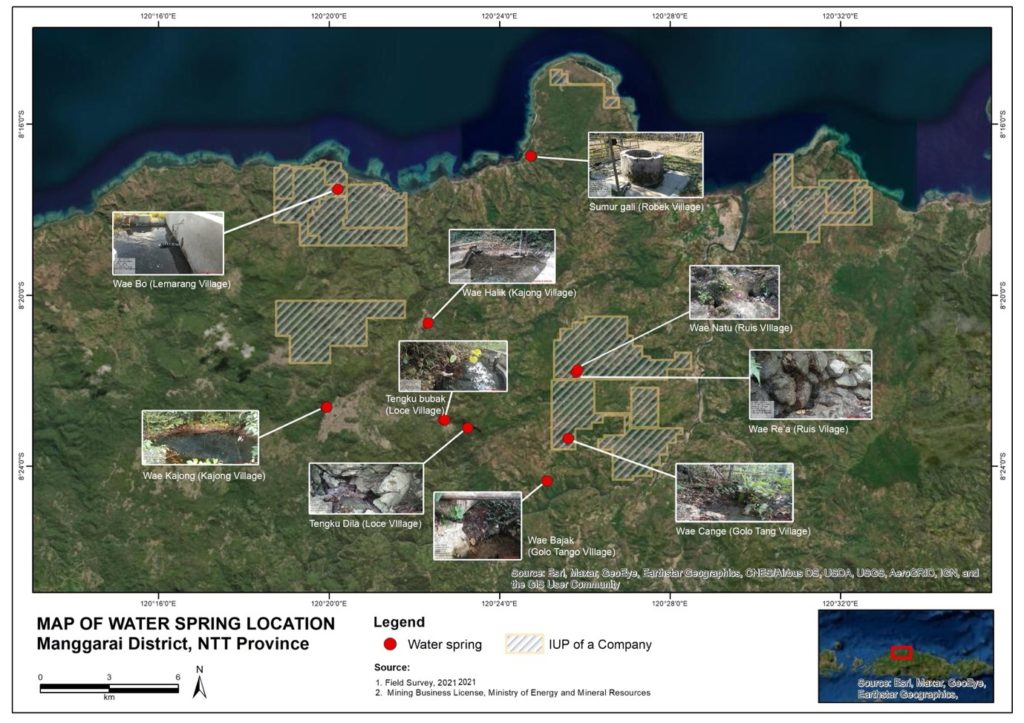

The spatial analysis found that three of 10 identified water springs are located precisely within permitted areas (Figure 2). The residents outlined that one of these springs has significant meaning for their cultural identity as it is the main location for villagers to organize water-related rituals. The local indigenous said that after mining began, well water turned black, smelly and tasted of “strangling inside the neck” when people drank it. The villagers suspected a serious intrusion of pollutants from dynamite explosions from the mining operation nearby. The water became normal when the mining operation was slowing down. In spite of that, the women in particular worried that people would potentially become sick due to water consumption.

Fig. 2.

The villagers also complained that a spring that used to produce large volumes of water became smaller once mining started. People keep accessing it regularly as it is the only water source within reach for villagers. They bring large containers to collect water and use it for a couple of days.

Although groundwater in some villages are out of the mining concessions, the area is hilly and mountainous which is risky for open pit operation of manganese mining to carry polluted materials into the downstream, rivers, and land. The stake of pollution is higher since the area is karst porous which is risked of polluted waste to infiltrate into the underground water system and contaminate the entire area. The area is semi-arid and highly relied on the underground water as the main source for basic uses.

Sustainability from the Source

The case of manganese mining in Manggarai is clearly underscores the need for sustainability from the first link of the supply chain. Currently, national laws such as Land and Water Conservation Law 37/2014, Water Resources Law 17/2019 and District Regulation of Manggarai on Water Protection Regulation No 5/2015 are heavily protecting groundwater. They prevent the spring locations from overlapping with exploitative activities. Heavy penalties including imprisonment are set to be applied to those who break the protection of these areas.

Customary laws also aim at conserving water by preserving forest cover in water spring areas and places that are sacred for traditions. The tradition also maintains the trees that are believed to protect the sustainability of the water supply from catchment areas. It is prohibited to chop down these trees and a heavy punishment can be incurred when a member of the community breaks that prohibition. In fact, the overall tradition of the indigenous peoples of Manggarai is placing a respect to water spring as the center of cultural procession. Without water spring, the identity would be lost forever.

Building on these laws as well as traditions, global demand for raw materials for renewable energy should be discussed seriously to include the sustainability from the original source of raw materials. Buyer companies should develop such approaches as a way to safe guard social, environmental, and economic sustainability.

Bernadinus Steni has been an environmental lawyer for more than 10 years and is interested in the issues of sustainability, particularly indigenous peoples and local communities’ rights.