More than Germany, the UK has reduced coal power and carbon emissions in recent years. Should we be talking more about the British model and less about the German one? More specifically, does Germany missing its 2020 carbon target put the country’s 2030 target completely out of reach? By Craig Morris.

The sun is setting on coal in the UK – what about Germany? (The joy of all things, edited, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Back in 2008, both Germany and the UK pledged an 80% reduction in carbon emissions by 2050 in the run-up to COP15 in Copenhagen. The British have performed better since then. An excellent overview of the UK’s power sector in 2017 by Carbon Brief shows that coal power dropped from 143 TWh in 2012 to a meager 23 TWh last year – a reduction of 84% – primarily due to the country’s floor price for carbon, which reached 23 pounds per ton last year. Germany only reduced coal power by 13% from 277 TWh to 242 TWh during the same timeframe.

And while Germany continues to phase out coal gradually and without a roadmap, the British government announced this month that all remaining coal plants in the country would be closed by 2025. As of 2016, the UK had reduced its carbon emissions by 36% relative to 1990. Germany is likely to come in closer to a 30% reduction by 2020, far behind its 40% target. To reach 55% by 2030, the country would therefore need to lower emissions by 2.5 percentage points annually throughout the next decade.

But there are reasons to be skeptical of British progress – and more optimistic about Germany. For the UK, the story starts with this take from Carbon Brief: “The 84% coal reduction over the past five years accounts for around 80% of the fall in overall UK carbon emissions over the same period.” In other words, like Germany, the UK has made too little progress outside the power sector. Put differently, the British have already picked their low-hanging fruit, while Germany’s is still on the branch. Consider the following:

- The economic case for the British transition from coal to gas: The UK imported coal but had affordable domestic gas reserves, still covering more than half of demand. Germany has coal, not gas.

- No jurisdiction with a coal phaseout has significant domestic coal reserves. As Canadian Prime Minister Trudeau put it, “No country would find 173 billion barrels of oil in the ground and just leave them.” Germany has lignite reserves that, depending on the estimate, could provide a fifth of German electricity at less than four cents for the rest of this century. Leaving that in the ground is a political challenge.

- Manufacturing makes up 23% of German GDP but only 11% in the UK. Energy-intensive business interests that oppose a coal phaseout are thus smaller in the UK, which helps explain the British success in implementing a carbon floor price.

Looking ahead, British and German plans also differ considerably. While Germany has made up its mind to go with renewables, the British still consider nuclear – including new reactors – to be necessary and have not given up on carbon storage. 2018 is also expected to be a breakthrough year for fracking in the UK. Potential conflicts between these options, especially inflexible nuclear to complement fluctuating wind and solar, are not addressed in the British debate but will become unavoidable.

In addition, Scotland is not playing along with Westminster; the Scots have banned fracking and aim to meet 100% of gross power consumption with renewables by 2020. The British thus lack a common vision, so expect a political back-and-forth. Most importantly, what’s missing from all of these plans is a massive renovation scheme in the building sector along with, for mobility, the construction of charging stations for EVs and a focus on walkable cities.

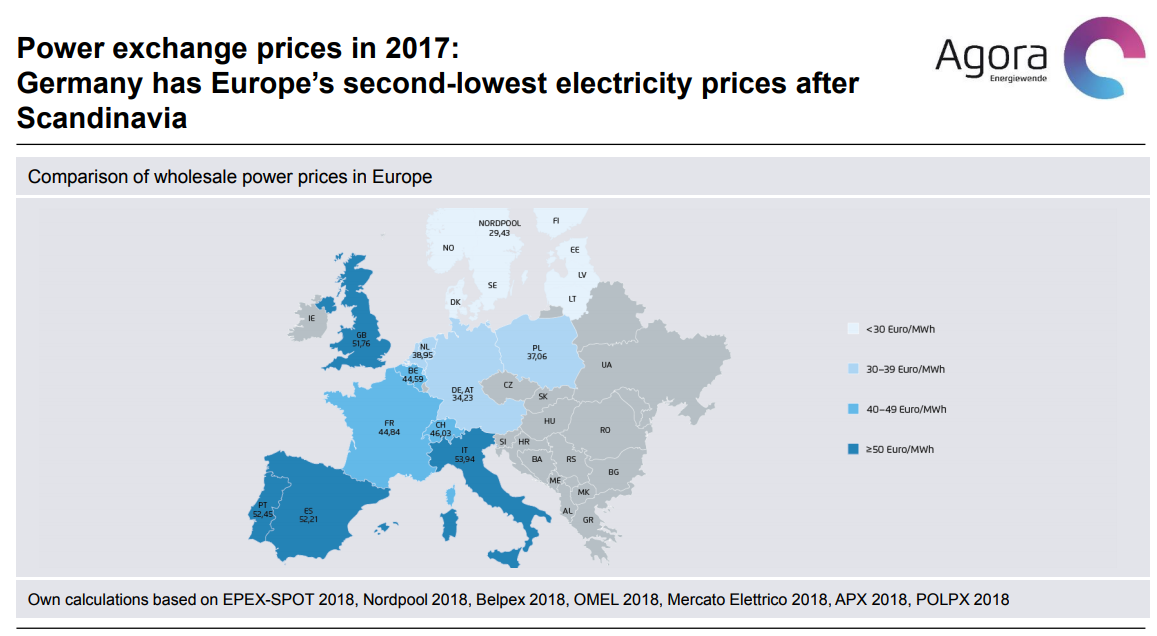

Germany is also doing too little with buildings and mobility but should make considerable progress in the power sector by 2030. The nuclear phaseout will remove all nuclear reactors by the end of 2022, thereby drawing down the surplus capacity causing record exports. (In 2017, British wholesale power went for 5.2 cents compared to 3.4 cents in Germany.) Coal power will immediately plummet without exports, and the further growth of renewables will push it back even more.

Germany could reduce its power generation from brown coal (lignite) by 38% from 134 TWh to 83 TWh if electricity exports and imports would be balanced like in 2011.

50 TWh less electricity from brown coal would save 60 million tonnes of CO2. pic.twitter.com/QWxHYS4xND— Bruno Burger (@energy_charts) January 9, 2018

The 2020s will therefore see the beginning of Germany’s coal phaseout with or without an official policy. That decade, German emissions are likely to drop faster than the UK’s – unless the British come up with a plan to pick the higher fruit of buildings and mobility. A 55% carbon reduction in Germany by 2030 will be hard to reach but not impossible – even with the nuclear phaseout.

Finally, let’s not forget that climate change is not the only issue, as important as it is. Prime Minister Thatcher devastated coal communities decades ago, and those in northern England just voted for Brexit. The UK is divided not only in the energy sector; the British still debate who they are. While it was bad for the climate, Germany’s commitment to coal regions in the past few decades was at least good for social cohesion, without which no energy transition is possible.

The UK looks to me to have a somewhat stronger policy overall on electric mobility. The most striking example is the London ULEV, an initiative of oddball London mayors not the national government, which has no real counterpart yet in Germany. London is such a large part of the UK economy that the initiative is likely to have wider effects. Tesco or Sainsbury are having to review their delivery fleets in the London region, and their decisions are not likely to be limited to it. In addition, all the carmakers in the UK are now foreign-owned, so the ICE lobby is much weaker than in Germany.

Agreed on the incoherence and wastefulness of British nuclear policy. I’d be be very surprised if the government, facing budget constraints after Brexit, will find the mate for the lonely Hinkley C white elephant. More undersea cables to Norway will look a much better option.

Eating carbon or heating carbon … the UK model:

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/fuel-poverty-killed-15000-people-last-winter-10217215.html

A barbarian society calling the paupers ‘fuel-poor’ raised the eyebrows of the entire European community.

€ 1 million is now being spend to find out if something like “fuel poverty” does exist at all:

https://extra.shu.ac.uk/ppp-online/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/fuel-poverty-european-union.pdf

From what I followed this winter Germany’s poor last 5 lives doe the cold so far, all either homeless, drunk, injured and/or sick:

https://www.hinzundkunzt.de/erneut-toter-obdachloser-aufgefunden/

Starving to death the elderly to polish the carbon household – what a perversion. But that’s capitalism, it looks good for those on the sunny side.

The visible carbon saving pledges in the UK cost lives, lives of the poor again:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/01/22/cladding-just-three-300-tower-blocks-replaced-wake-grenfell/

“From what I followed this winter Germany’s poor last 5 lives doe the cold so far, all either homeless, drunk, injured and/or sick”

To be fair, comparing Germany’s death toll from this year’s winter to the UK’s death toll from previous years is rather like comparing apples and oranges. This year’s winter in Germany has been extremely warm. Even here in the north-east (which usually doesn’t get much benefit from the maritime climate heated by the Gulf Stream like West Germany does, but which gets a continental – i.e. Russian – winter instead) has seen almost no snow and only one or two nights of serious frost (below -5°C) thus far. For most days, it hasn’t been freezing at all this winter, the ground is unfrozen and the crocusses are already starting to bloom, and even the tulips have been sprouting for weeks now (normally this happens in April). In previous years, even in the last few rather too warm winters, we would have near-continous freezing temperatures all through January and probably through February as well.

I have no comment on the relative merits of UK and German energy policy as regards the welfare of the homeless in winter. However, I would say that degrees are not simply degrees when it comes to human comfort and well-being. I have lived in south-eastern Australia and in eastern Western Siberian (Novosibirsk). To natives of the latter location, it is a howling joke when I tell them that in highland central Victoria it can often drop to below zero overnight, and when it doesn’t rise again above eight, it can feel miserably cold. What people overlook is that, around ice point is deadly for heat transfer. The air is generally still damp, as is the ground. That’s a really harsh environment for anyone trying to sleep and survive on the street. My experience of Novosibirsk is that the best winter weather is when it’s between about -8 to -15, provided it’s not windy (big if). I used to say that minus 35 and still was better than minus 15 with the wind in your face. That latter is still no fun. Nevertheless, having one January experienced two weeks solid of -30 to -40, I decided that it was after all not Bali.

In Japan the poor used to send their elderly to the mountains.

The closure of the UK’s coal power plants was due to the pollution caused by them, not due the floor price of carbon.

These power plants were illegal under environment legislations.

“As of 2016, the UK had reduced its carbon emissions by 36% relative to 1990.”

Funny, UK media claim that they have cut their greenhouse gas emissions 42% from 1990 levels, citing government sources. I think German pledge also concerns GHGs, not carbon.

http://www.independent.co.uk/environment/uk-greenhouse-gases-fall-climate-change-a7658981.html

PS

(missing links to the UK carbon program)

Tony Blair’s solution (“Bony liar’s” ) was to build atomic power plants and to build atomic war heads/ bombs and submarines causing the death of over 20.000 people due to “fuel poverty” during the winter 2011/2012:

http://www.europe-infos.eu/europeinfos/de/archiv/ausgabe165/article/6116.html

The European Union must turn to Manchester (“manchester capitalism”) to define the term “fuel poverty”:

http://www.europe-infos.eu/europeinfos/de/archiv/ausgabe165/article/6116.html

The report will be finished after the Brexit.

It is getting worse, they die like the flies:

https://www.eua.org.uk/cold-homes-worsening-britains-mental-health-crisis/

https://www.eua.org.uk/uploads/5A6F434678A28.pdf

Mental illness makes them vote for the Nazis, for Brexit, for war.The paupers are the victims of the rich.

The Bony Liar has fooled them.