Germany might remain without a new government for some time, due to fundamental differences between the parties likely building a coalition: the conservative CDU, the libertarian FDP and the German Greens. But, says Craig Morris, the rise of the far right should not be overestimated.

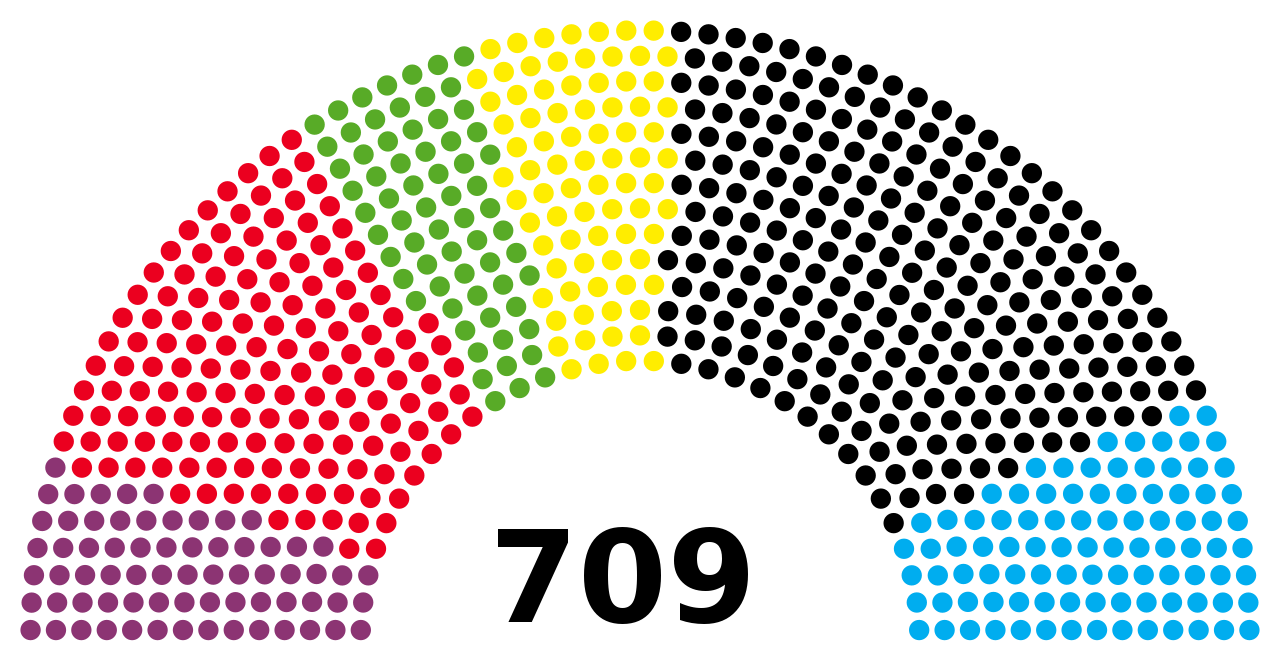

The likely coalition includes the Greens (green, 67 seats), the FDP (yellow, 80 seats) and the CDU/CSU (black, 246 seats). (Public Domain)

First, the good news: 75 percent of Germans voted on Sunday, up from 71 percent in 2013. One reason is that the far-right AfD (Alternative for Germany) gave voters a broader spectrum of parties to vote for. In this respect, the party strengthened German democracy. In other respects, statements its politicians make cut at the root of democracy.

It will thus be interesting to see how the next four years will shape the AfD. The party could embarrass itself out of office or transform into a more respectable version of a party to the right of the CDU and its Bavarian sister the CSU.

The bigger story tonight:

Merkel lets more than one million refugees into Germany and then still manages to become Chancellor again.— Wolfgang Blau (@wblau) September 24, 2017

After two years in which #Germany took in over a million refugees and migrants, 87% voted against hate. That's something. Good night. ?

— Christian Odendahl (@COdendahl) September 24, 2017

We should not underestimate, however, how strongly German civil society will reject the current AfD. Already, #87Prozent has become the rallying cry for AfD opponents (the party got 13 percent of the vote). Even Germany’s biggest tabloid, Bild-Zeitung, will have none of the far-right nonsense and has bashed the AfD consistently over the past few years.

#btw17 commentary by largest tabloid @BILD – "It could have been worse (still)" – asking: "Will we now get Jamaika" pic.twitter.com/aRfTJfjBNK

— Sven Egenter (@segenter) September 24, 2017

Without wishing to conflate different political trends, I would also remind readers that Trump received 46 percent of the vote with anti-immigrant ideas in 2016, and Le Pen got 34 percent in France. Perhaps the Netherlands is a better comparison; there, Geert Wilders got 13 percent of the vote this year, and six parties entered parliament with at least 9 percent of the vote. Germany now also has six parties in parliament, with the far-right at 13 percent of the seats. That comparison is encouraging: the Dutch have a resilient democracy and are keeping their far-right party in check while also allowing it to participate in the democratic system.

Difficult coalition of #CDU, libertarian #FDP and #Greens only option now that #SPD pledges to enter opposition https://t.co/lvJ2dXHy9j pic.twitter.com/dcORwRl1KH

— Craig Morris (@PPchef) September 25, 2017

As the chart above shows, the “Jamaica” coalition (named after the parties’ colors) is the only feasible option now that the SPD has declared it will not enter a new grand coalition (GroKo) with the CDU. On the one hand, GroKo isn’t so grand anymore; it fell from 68 percent of the vote to 54 percent. The SPD got a lot of its program implemented, but voters do not tend to reward a successful smaller coalition partner. On the other, the SPD did not want to let the AfD become the largest party in the opposition.

It may be some time, however, before Germany gets a new coalition. Fundamentally incompatible positions between the FDP and the Greens will slow down talks. For instance, the FDP wants the market to take care of everything, so it will call for all support for renewables to be done away with; instead, the (ineffective) emissions trading platform would be the only instrument to mitigate climate change. The Greens will point out that a bouquet of policies are needed; emissions trading is fine (in theory) for cleaning up industry, but not in helping coal communities where jobs are lost or in rolling out a mix of technologies needed for the future.

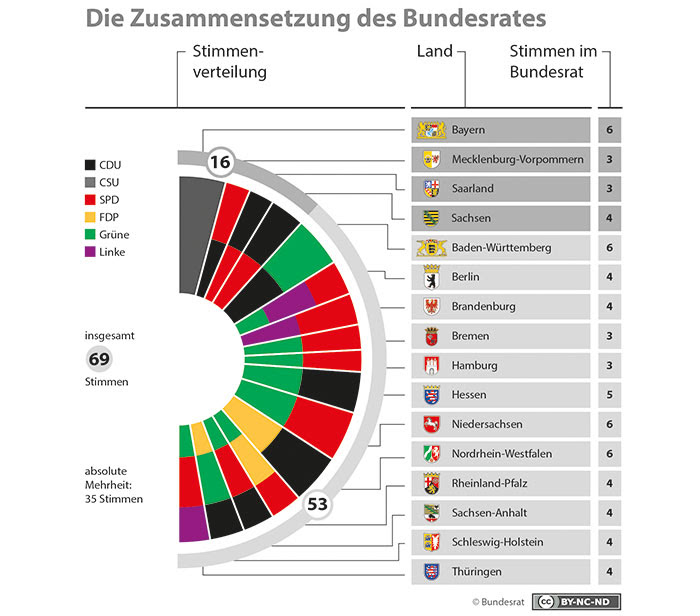

One other obstacle is the state elections coming up in mid-October in Lower Saxony. Earlier this year, a Green Party member of the state parliament switched to the CDU, costing the SPD/Green coalition its majority (in German). Though it has shrunk to only 20% of the vote at the national level, the SPD is still the strongest party at the state level – and hence in the Bundesrat. The CDU could get a majority of seats if it takes back Lower Saxony, but only including coalitions with the SPD.

Regardless of the outcome of the upcoming election in Lower Saxony, the Jamaica coalition in Berlin will not have support in the upper chamber of parliament. In the meantime, coalition negotiations in Berlin might hang in the lurch while everyone awaits the outcome in Lower Saxony.

And this is the real obstacle: German politics could be paralyzed over the next few years with a difficult coalition that lacks support in the Bundesrat, and the AfD might – against all odds – manage to stop its infighting long enough to benefit. It’s unlikely, given the party’s previous incompetence, but stranger things have happened. In the process, the Greens could suffer greatly; the CDU and the FDP have more in common, so the Greens are the “third wheel,” so to speak. Whatever happens, German energy and climate policy is on hold for now.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

The graphics on the composition of the Bundesrat is nice, but it is outdated. Nordrhein-Westfalen has a CDU-FDP government and Schleswig-Holstein has a Jamaica coalition.

Stasis on electricity, sure. But on transport? Neither the FDP nor the Greens should on paper be friends of bailing out German carmakers by say blocking city bans on polluting vehicles such as diesels.

The composition of the Bundesrat ist not up to date. This picture seems to be from 2013. In Thüringen ist the Linke leader of the coalition, not the CDU.

France competing with Germany : hefty CO2 tax for FITs

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-budget-carbon/france-raises-carbon-taxes-to-repay-edf-renewables-debt-idUSKCN1C21DL?il=0

and good prospects:

http://www.filiere-3e.fr/2017/09/27/photovoltaique-apres-annees-difficiles-de-nouvelles-perspectives-20172018/

machine translation:

https://translate.google.com/translate?sl=fr&tl=en&js=y&prev=_t&hl=de&ie=UTF-8&u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.filiere-3e.fr%2F2017%2F09%2F27%2Fphotovoltaique-apres-annees-difficiles-de-nouvelles-perspectives-20172018%2F&edit-text=

I don’t know if the 2nd article was written after the CO2 tax announcement or before.

The “French” CO2 tax could be exactly what the FDP needs to agree on a German climate progress.

Are aviation and marine included in the French CO2 tax?