After several years of North Americans criticizing EU biomass policy for leading to imports of wood pellets to Europe, the European Union now complains in the other direction—that the US should stop flooding the EU with biomass. Craig Morris explains.

Clear-cut forests in Oregon; the EU and the US need to work together to make biomass harvest more sustainable (Photo by Calibas, edited, CC BY-SA 3.0)

It all started back in 2014 at the latest: North American groups began charging that the EU’s policy of co-firing wood pellets in coal power stations should be discontinued because more and more forests in the United States in particular were being cut down. As I pointed out 18 months ago, however, Germany is clearly not the problem. The country remains a net exporter of wood pellets, which it largely makes from waste wood sourced locally. Only 0.07% of German electricity comes from fresh timber, most of it in cogeneration units that mainly produce heat—electricity is a byproduct that increases the overall efficiency of the process.

Germany does not import significant quantities of wood pellets from the United States. The UK is the main culprit with its Drax power plant. Belgium, which recently became the largest country in Europe with a completely coal-free power supply, comes in second (though there is word that Belgium is rethinking its policy of promoting the co-firing of wood pellets in coal plants). The question is whether the decommissioned coal plant at Langerlo will be switched over to pellets completely in 2018 (report in German). Another woody biomass facility might also be added in the French-speaking part of the country by the end of the decade to replace one only 40% as large as the proposed project (report in French)—and GE plans to build one of similar size in Ghent.

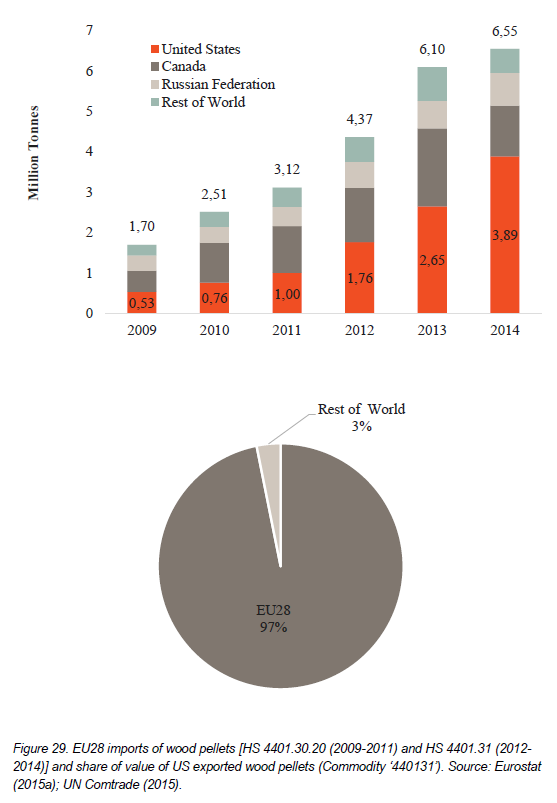

Now, the European Union has chimed in with a 364-page PDF entitled “Environmental implications of the increased reliance of the EU on biomass from the southeast US.” It finds that 97% of wood pellet shipments from the US go to the EU alone. The five main importers are the UK, Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, and Denmark—and the UK alone makes up 73.5% of US exports. The word “Germany” does not appear in the body of the study.

Demand for wood pellets within the EU may be growing, but the inordinate production increase from the US also requires some explaining. Source: European Commission.

European officials are not happy about this outcome. They worry that natural forests are being turned into plantations, which reduces biodiversity—and the entire process is of questionable value towards mitigating climate change. The study proposes 12 policy tools to improve the situation, three of which are considered to have the greatest potential:

- a quota on the share of primary biomass wood pellets by specific energy producer;

- a “material hierarchy” requirement; and

- a ban on biomass types of high-value.

The first policy tool might mean that plants fired solely with wood pellets from fresh timber might no longer be supported. The latter two tools focus on shifting consumption from wood types of high-quality towards waste products.

Biomass certification would be an obvious starting point, but the market is splintered, with various certification options, each of which has a cost impact—and the price tag may scare off smaller forest management companies.

Otherwise, the EU experts say that there is only so much they can do; all of the proposals would mainly only apply to businesses based in the EU. The study investigates ownership of forests in the southeast US and finds that most of it (87%) is in private hands. Forests that are family-owned reportedly often do not primarily pursue income from harvesting, while corporate landowners are “the most price responsive in their willingness to supply wood to markets.” Unsurprisingly, profits are “the primary ownership objective” for the latter. But in the southeast, family-owned forests reportedly tend to be managed with a greater focus on profits than is the case in other parts of the US.

In investigating not only what the EU but also the US can do to make woody biomass harvest more sustainable, the study provides a quite interesting overview of the legal framework in the US. As so often is the case, individual states have as much impact as the federal government.

In the end, we have an undesirable situation that can only be solved if both sides work together. Fortunately, the study itself is evidence of interest on both sides: it was co-authored by US experts.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

The biomass plant to be built by GE in Belgium (the BEE project) will not be built as it did not obtain subsidies by the Flemish government eventually. The Langerlo project obtained federal support by the previous government, although politicians don’t want this project to be executed. The Belgian government is slowly turning its back on big biomass plants. How the renewable energy share will be reached is unclear as subsidies for solar have been cut dramatically and the terrible spatial planning does not leave enough room for a big increase in wind energy production. But American biomass will not be the source!

The long-range argument against wood pellets is that we don’t have many options to get to the 1.5 deg target, which implies large-scale sequestration, other than reafforestation. So even a net-zero forestry system is not enough, we need to go for maximum growth and carbon-fixing. That does not necessarily mean just reversion to wilderness. You might get better carbon fixing from intensive management, which would generate some biomass from thinnings, as well as construction timber at maturity. But I doubt if it would be compatible with any clear-felling.