In Germany, energy democracy has been a central pillar of the Energiewende. Now, a British research team has proven that in 2050 half of the UK’s electricity could come from small-scale civic projects if the energy sector is reorganized accordingly. Stephen Hall summarizes the findings.

What if everyone did this? (Photo by Wayne National Forest/Alex Snyder, CC BY 2.0)

What would our energy system look like if the move to a low-carbon society wasn’t left to governments and big energy companies but was instead led by civil society?

We are all used to the debate between states and markets, private vs public provision in shaping the direction of the energy sector; but communities, citizens and local authorities together can form a “civic” energy sector that could revolutionise the way we generate and use energy.

People in the UK are not well served by the current energy market. Investigations have found poor competition, a slow switch towards renewables, and the value in the system being captured by international companies, with very little economic benefit remaining at a local level.

But there is another way, identified by Realising Transition Pathways, a consortium of researchers from across nine UK universities. Existing community energy projects – run by groups of citizens – could link with new roles for local authorities as energy service companies to form a “civic” energy sector.

This civic sector would expand on the work of energy crowdfunding platforms such as Pure Leapfrog and mutual models such as Energy4All to provide new ways for ordinary citizens to invest in local energy resources.

The growth of a civic energy sector would be bad news for the large utilities. The UK’s traditional Big Six energy providers would lose ground in both the generation and supply markets and would need to shift their business models to provide new services. Civic energy would need some early support, but it could soon become the natural preference over what an increasingly outdated utilities sector is offering, having failed to anticipate the potential of local energy and what customers want from their energy providers.

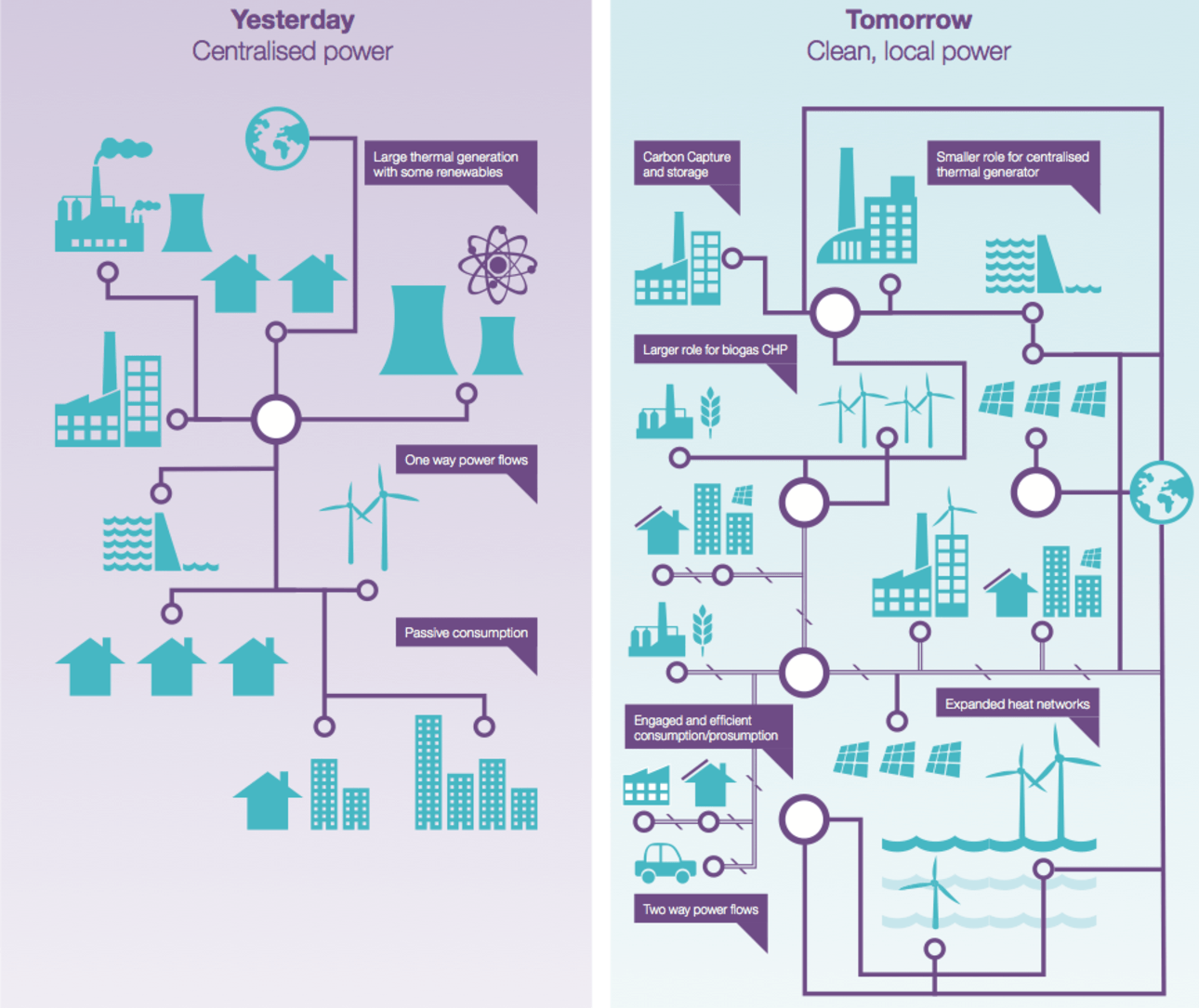

Distributed energy would need both technological and institutional change. It would require lots more small and medium scale renewables – more solar, onshore and offshore wind, biogas heat and power plants, and marine energy such as tidal generation. All of these new technologies would need to connect to much smarter distribution grids than we currently have and would require new ways of moving power from the bottom up as well as the top down.

However our work shows that local energy doesn’t mean energy independence; indeed in a civic energy future, interconnection between regions, across the UK and internationally would be critical to balance the system. This wouldn’t mean an end to big power plants, just far fewer of them.

These connections would be aided by a smarter, more responsive electricity grid. This could mean a shift to tariffs based on when you use energy rather than how much you use. Consumers would have to be much more engaged. In order to develop a distributed energy system households and businesses would need to get serious about energy efficiency and be more responsive to smart meter data.

Local authorities will also be vital as, in a distributed network, consumers would likely get bills from their local authority energy company. These bills would be for services such as a “warm home” or “hot water” as opposed to the relatively crude system of just paying for energy by volume needed.

The old system of paying for how much you use means big utilities can’t stomach a big fall in consumption, so why would they help you really reduce your bill?

If you were paying for “heat” and “light” rather than power by the unit, your energy supplier would want to to keep you warm and your house lit as cheaply as possible, which means big investments in energy efficiency. Local authorities are in a great place to do this as they are trusted far more than current utilities.

But of course not all local authorities have the same resources. The north-west of England is not as suited to solar as the south-east, for instance, and the mountainous north of Scotland can provide much more hydro-electricity than the flat farmland of the Fens.

In order to move to a distributed energy system, we would need to carefully plan for maximising energy resources in each region. Achieving this new type of energy system will be challenging – but it is possible.

Stephen Hall is a Research Fellow in energy economics and policy at University of Leeds. This post is published under a CC BY-ND 4.0 license and was first published at The Conversation.

Energy produced locally is also more efficient as less is lost in lengthy transition pathways. It has also been shown that people that generate their own power see it as a finite resource and use it more sparingly.

Energy produced locally by mini-plants will always be much more expensive per unit. It is all very well admitting that we will still need large plants, but essentially we will still need a lot of them.

Say we have a lot of solar in the UK as is being planned. Solar has a credit capacity of zero. It will not displace a single thermal power plant.

Take wind. It will have a credit capacity of less then 10% so we will still require all the conventional plants we have.

Ah, I hear you say. All we need is storage. Scotland certainly has some potential for pumped storage but since the UK government is wedded to markets, and the big 6 are sitting on their hands waiting for a guaranteed high profit incentive, no scheme has started.

And there is the rub. In a market driven approach, every proposal, large or small, will always have to be subsidised. Even the concept of community benefit will have to be paid for by another community.