In an interview, one of Germany’s foremost energy conservation experts, Stefan M. Büttner, says that companies can save energy and production costs more easily than they think.

Industrial energy consumption as well as the individual and individual companys must be adressed. (Photo by Tom Blackwell, CC BY-NC 2.0)

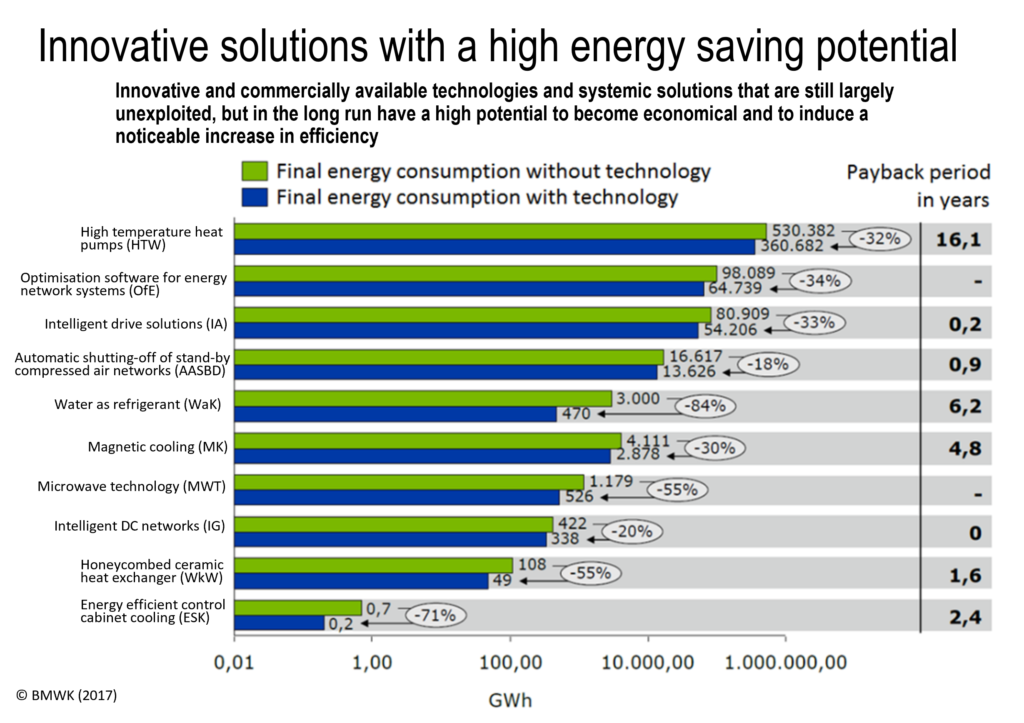

“At least one third of industrial energy consumption can be saved by innovative technologies currently available on the market,” says Stefan M. Büttner, who is director of global strategy at Stuttgart University’s Institute for Energy Efficiency in Production (EEP), as well as chair of a UN task force on industrial energy efficiency. “There are some technologies, like cooling systems that use water as a refrigerant rather than synthetic refrigerants, that can cut energy consumption by 84 percent,” he adds. Some of them, like electric drives or pumps with variable speed, pay back investment in less than a year, others like the water-based refrigerants might take six years.

On an impressive list of quick-fixes, Büttner includes the likes of high temperature heat pumps, optimisation software for energy network systems, intelligent drive solutions, automatic shutting-off of stand-by compressed air networks, magnetic cooling, microwave technology, intelligent DC networks, honeycombed ceramic heat exchangers, and energy-efficient control cabinet cooling. With the savings they bring, most of these devices cover their own cost in less than two years, says Büttner.

Fig. 1

This palette of technology may sound like science fiction to laypeople, but this is the world of energy conservation in industrial processes, which is the domain of the Stuttgart EEP. The institute describes itself as “a hub for industrial decarbonisation,” the mission of which is to increase energy efficiency in manufacturing and other industrial applications. Its staff includes experts on energy flexible production, industrial microgrids, storage, and industrial heating and cooling. It works closely with the private sector and policymakers: on the demand side of the Energiewende.

The war in Ukraine has put energy usage front and center: energy not consumed is energy that Germany doesn’t have to buy from Russia. And it has been Germany’s industrial sector, led by the Federation of German Industries (BDI), that has protested most vociferously against the possibility of an embargo on gas and oil from Russia. Germany relies upon Russia for up to 55 percent of gas and 34 percent of oil supplies, according to the think tank Agora Energiewende. The concrete, chemicals, steel, and plastics industries in particular depend very heavily on Russian gas and claim a cut-off would doom their fortunes. Germany’s industrial sector is responsible for a quarter of German natural gas consumption.

But change is in the wind, and whether it be in the short or long-term, German industry will be weaning itself off Russian fuels. Energy conservation will play an enormous role in this transition, says Büttner. “For a complete changeover, we probably need 10 years, a lot of money, a lot of heat pumps, and a lot of hydrogen or additional generators. There are still many regulatory challenges, too. But,” Büttner emphasizes, “this can happen.”

Transparency, he says, is key: we have to know how much energy is being used, when and where, if we want to streamline these processes. “So many companies, especially smaller ones, don’t know where they stand in terms of energy use and their potentials. Only when they know where they stand, will they be able to draw an effective route of action.”

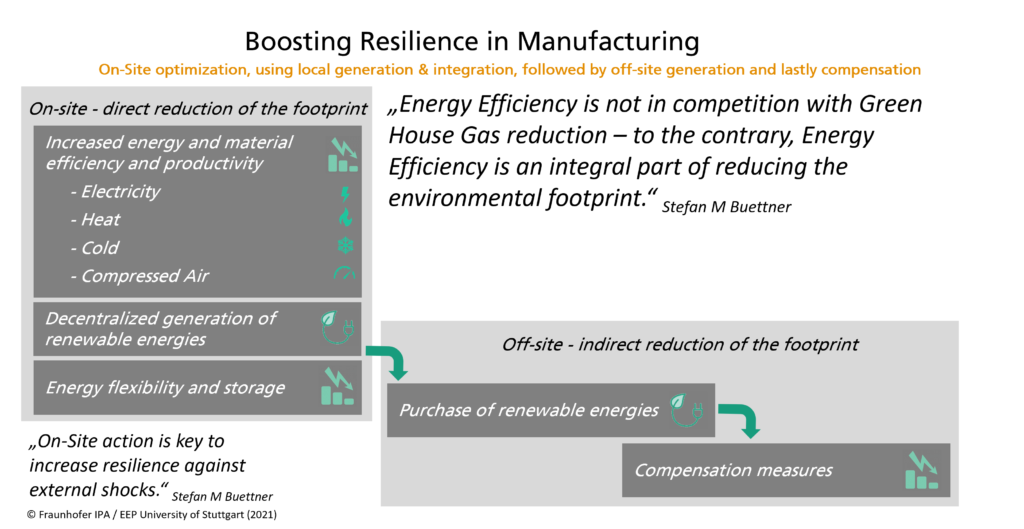

Aside from the industry-specific technology, the way to cut energy consumption isn’t so different for individuals, corporations or whole economic systems, he says. It is all about decreasing dependency and increasing resiliency. “Everybody has to be more self-sufficient and that decreases costs,” he says. The generation of wind, solar, and geothermal energy take years to get up and running, says Büttner, pointing out that some corporations, such as BASF, build their own wind parks. But saving energy can also be cheap and quick, he says: “There’s a whole world of energy efficiency that most people and companies don’t know about.”

Fig. 2

Whether at home or on the factory floor, the most critical pressure point is space heating. There doesn’t have to be a law mandating lower room temperatures, says Büttner, but rather awareness programs that show people and companies how much energy they can save — namely 6 percent — if they lower temperatures by a degree or two.

The Covid epidemic and the Ukraine crisis, says Büttner, are “disruptive moments” that can prompt a sea change in efficiency. “We reduce dependency from Russian imports, decarbonize, stabilize supply chains, and cut energy consumption costs all at the same time,” he says.

Bottoms up

This revolution, Büttner is convinced, has to come from below. “Decarbonization and the transformation of the energy system are often considered top-down,” he says. “In Brussels as well as at the UN, the focus of decarbonization has long been on sustainable generation, transmission, and compensating emissions, like through carbon pricing. But optimization on the consumer side, namely the reduction of energy consumption, is often neglected, especially in the industrial sector. In view of the long planning and approval processes, the lack of acceptance for generation and transmission infrastructure, and the ambition to become less dependent on fossil fuels, more bottom-up is needed. That means optimizing local and community consumption,” says Büttner.

“If millions of actors of their own free will and conviction keep their eyes open for well-communicated savings potentials, no matter how small they may be, the effect will be much stronger than intangible, generic regulations that can be understood as an encroachment on individual freedom.”

In the corporate context, says Büttner, in many cases it is not the lack of money that prevents firms form taking efficiency measures, but the risk of venturing into the unknown. “It is easier to focus on what one knows and can do, like increasing sales, rather than taking the risk involved in saving energy costs.”

“To really make progress we have to address the individual and the individual company directly,” says Büttner. Europe’s goal may be climate neutrality by 2050 or independence from Russian fossil fuels, but the question has to be what you as an individual or as a company can contribute. The trick is to trigger self-initiative and self-commitment. Otherwise one can just hide behind the masses and avoid individual responsibility.”

“Climate targets are set by the state, but they can only be achieved effectively if individuals support them,” stresses Stuttgart University’s director of global strategy for energy efficiency.