Many Central and Eastern European countries rely on Russia for more of their fossil fuel than Germany does. This is one reason why Russian president Vladimir Putin targeted Bulgaria and Poland when he announced that these two EU and NATO countries would no longer receive natural gas deliveries. Paul Hockenos spoke with Bulgarian energy expert Radostina Primova.

The current energy-crisis is an opportunity for Bulgaria to expand renewable energies (Photo by Klearchos Kapoutsis, CC BY 2.0)

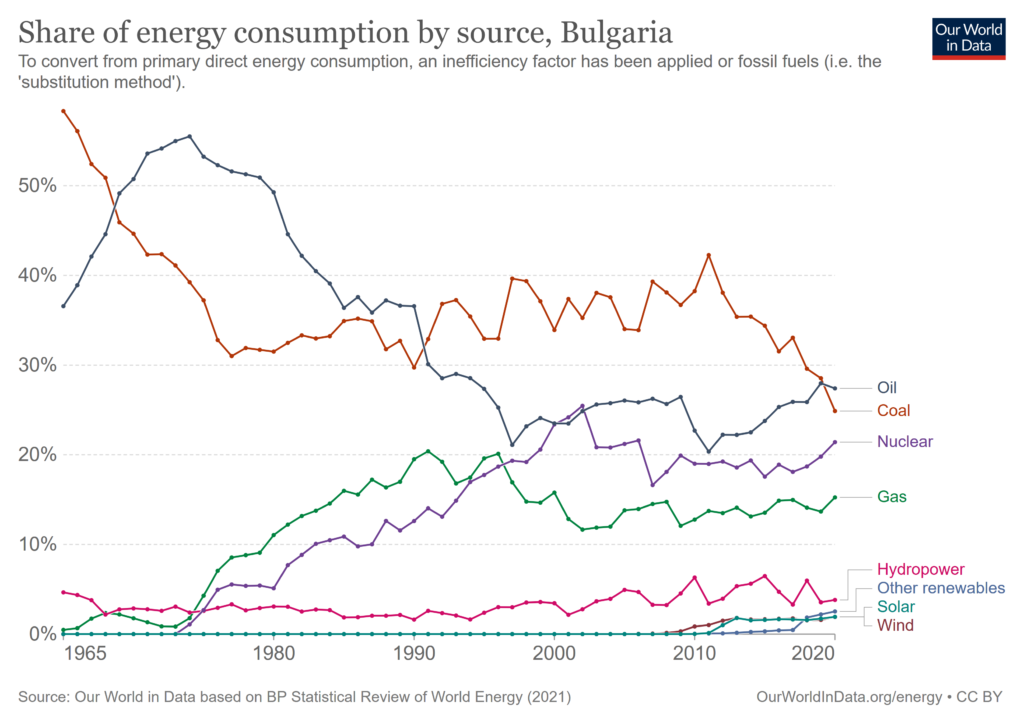

Until April 27, Bulgaria imported almost all of its gas and oil from Russia. Thus Moscow’s snap decision to halt all gas exports to Bulgaria has upended business as usual in the country. But the crisis is an opportunity for Bulgaria to expand renewable energies and invest in energy efficiency solutions – rather than merely replace one gas supplier with another.

In line with EU strategy, the Bulgarian government had already announced that it would not renew its ten-year contract with Gazprom that expires at the end of this year. Today, the country buys about three billion cubic meters of gas a year from Russia, almost all of it via the TurkStream pipeline running under the Black Sea from Russia to Turkey and then on to the EU.

Bulgaria’s intention is to import gas from Azerbaijan through a new pipeline in Greece. Additional quantities of LNG are expected from the terminal in Alexandroupolis in eastern Greece, in which Bulgaria has a stake.

Fig. 1

But experts in Bulgaria like Radostina Primova, Senior Analyst at the Center for the Study of Democracy in Sofia, say switching gas suppliers is just one alternative – necessary in the short-term but not a strategy that will help the country meet its climate targets. “The energy supply crisis in the context of war situation in Ukraine could be the trigger for Bulgaria and other Eastern European countries to accelerate their delayed energy transition, decentralize energy supply, and at the same time remove Russia’s fossil fuel grip,” explains Primova. Renewable energy is a means for Bulgaria to end its energy poverty once and for all, she says.

Despite its high gas and oil import shares, Bulgaria is among the countries with one of the lowest overall total dependencies on gas in the EU – about 12% of its energy mix – and, therefore, relatively well positioned to survive without Russian gas, she says.

Oil is another story. Russia supplies all of the crude oil that Bulgaria processes and consumes. The country’s only oil refinery is controlled by the Russian company Lukoil, which supplies two-thirds of Bulgaria’s end-user fuel.

But, says Primova, Bulgaria could also switch to more sustainable alternatives and “speed up the integration of renewable energy deployment through investments in innovative technologies such as the development of offshore wind energy in the Black Sea, enhancing energy efficiency measures in the residential, transport and industrial sectors, and utilizing its long-term potential capacity for decentralized PV-based power generation, which is estimated at more than 5.4 TWh per year, one-seventh of the current power consumption in the country.”

Studies show that Bulgaria has one of Southern Europe’s richest renewable energy resource bases.

The solidarity mechanism developed by the EU to ensure resilience to gas supply disruptions will be used to protect the most vulnerable consumers from abrupt disruption of supplies. But to activate this mechanism, the Bulgarian government needs to take immediate measures to conclude bilateral solidarity agreements with Romania and Greece in line with the guidelines provided by the EU, says Primova.

Finally, says Primova, the accommodation of a large share of variable renewable energy sources would require public investments in a modern, flexible, and resilient power system and closer integration with the wider European power market.

The decentralisation of the power grid will not be possible without the integration of smart grid technologies, allowing better monitoring and control of the system and further ensuring the security and efficiency of supply.

Bulgaria will likely become a net importer of electricity over the next decade, says Primova, which means that security of supply would depend on much better regional cooperation between transmission system operators and an upgrade of the cross-border transmission capacity. Southeastern Europe remains poorly integrated into the Western and Central European grid, says Primova, which presents a key impediment to a fully decarbonized electricity system.