An ad hoc statement issued by the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina on March 8, 2022, argues that Germany could pull it off – without nuclear power. Paul Hockenos explains.

The majority of Germans would support terminating energy imports from Russia. (Photo by Lewin Bormann, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Volodymyr Zelensky, the Ukrainian president, is loudly calling for the halting of fossil fuel imports from Russia, as are now many public figures in Germany and elsewhere.

After all, no one can ignore the absurdity of the contradiction: applying economic sanctions to Vladimir Putin’s Russia, on the one hand, to pressure him to stop the invasion of Ukraine, and at the same time the world is spending about a billion euros ($1.1 billion) a day on Russian hydrocarbons. Oil, gas, and coal are the country’s most lucrative exports and about 15 percent of its GDP, which Russia depends upon to finance its 60-billion-dollar-a-year military.

In the German media, the Christian Democrat MP and foreign policy expert Norbert Röttgen has argued: “The war is a business model for Putin, and we are financing it! So what are we waiting for? How many bombed cities are enough? I am convinced that the oil and gas embargo will come.”

In the light of Putin’s undeterred assault, ever more European politicians and experts are now considering what just a week ago sounded unhinged: terminating all energy imports from Russia. Of course, Putin has threatened to cut the supply from his end, should the West not acquiesce to Russian demands. The result, of course, would be exactly the same.

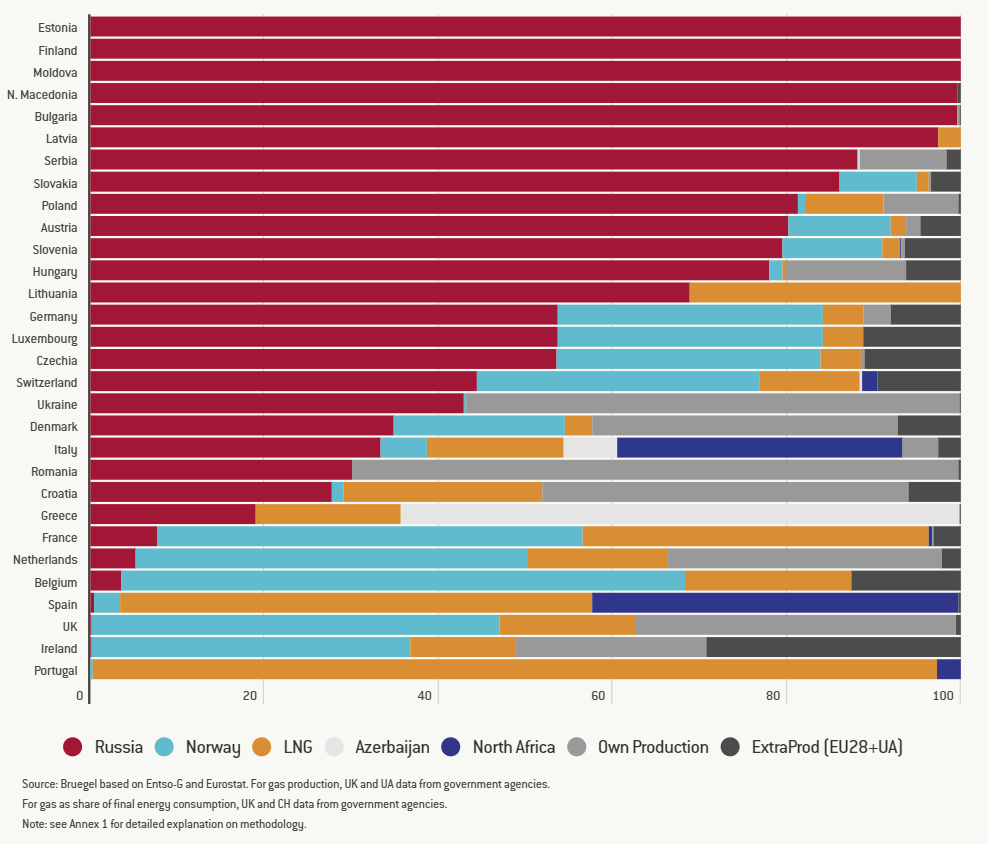

The crux of the problem is that Europe depends on Russia for 40 percent of its natural gas, 35 percent of crude oil, and 47 percent of coal. In most of Europe, gas is used primarily in buildings for heating and cooling, in industrial processes, and in the energy sector, as electricity, for balancing intermittent renewable energies by jumping in when the wind doesn’t blow and the sun doesn’t shine. An abrupt cutoff would constitute a gigantic lurch into the unknown – one that could have enormous repercussions for European industry and lifestyles, particularly in Germany and Central Europe, which are particularly reliant on Putin’s pumps.

Figure 1: Attribution of Gas Imports to Individual Sources in 2021. (© Bruegel, to be found here, written by Ben Mcwilliams, Giovanni Sgaravatti, Simone Tagliapietra and Georg Zachmann)

Among a handful of German and European think tanks, in a new report [in German], Leopoldina, Germany’s National Academy of Sciences, argue that going cold turkey is doable and that western Europe is prepared to weather the fallout. Leopoldina argues that “a short-term halt in the supply of Russian gas would be manageable for the German economy. Bottlenecks could arise next winter, but the negative effects could be limited through a package of immediate measures to reduce negative effects and cushion the social impact.”

“For Germany, at least, it wouldn’t spell the end of the world,” says Professor Robert Schlögl, vice-president of Leopoldina and director at the Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society in Berlin and founding Director of the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Energy Conversion in Mülheim an der Ruhr. “Sure, energy prices will shoot up, but the economy would be able to weather an abrupt cutoff and eventually compensate.”

Schlögl says that significant government support would likely be needed to protect consumers against price hikes and to encourage the transition to renewable energy, which is ultimately the medium and long-term goal of switching away from Russian gas, and indeed all natural gas. The private sector may have to be relieved of energy taxes.

The first move – whether the transition, now inevitable, be cold turkey or long term – is rigorously seeking alternative sources of natural gas and stockpiling gas reserves hand-over-fist with next winter in mind. Gas, though, is far harder to come by than oil and coal and particularly critical for Germany, which relies heavily on Russian gas to run its chemicals, fertilizer, concrete, and steel sectors. A third of German industry’s relies on gas, as well as half of all buildings for heat and cooling.

Leopoldina says that the obvious candidates to tap for additional gas, such as Norway and Qatar, can probably chip in a little more, especially in terms of liquid natural gas (LNG), but not that much more. They’re basically selling everything they produce now. And Germany, for example, doesn’t currently boast even a single LNG terminal.

Brand new EU guidelines will require that European gas storage facilities be at least 90 percent capacity by the onset of next winter – a viable but costly exercise.

This stash, even were it to materialize, would not last the winter long. This means that even in the event of a successful scrambling for and distribution of extra gas supply in Europe, there’d be a 10 to 15 percent short fall.

How to cover this best-case-scenario gap is where the heavyweights diverge. According to Leopoldina, Europe could wing it, though it wouldn’t be pretty. It implies state intervention in the economy to manage demand, namely by prioritizing essential sectors, deprioritizing others. The International Energy Agency says ordinary citizens would have to turn down their thermostats by 1 degree Celsius; German experts think a whole 2 degrees more conducive, which could cut household heating costs by 15 percent and reduce Russian gas imports by an estimated 10 percent.

But supply is more than gas. Since ramped up renewable energy could not take over straightaway, aging coal-fired plants and nuclear stations (which are scheduled for retirement everywhere in Europe, even where new generations of the latter are envisioned) could remain in service longer than planned. Röttgen advocates exactly this, and admits that Germany’s emissions balance will suffer.

Schlögl, however, argues Germany’s last nuclear plants lack the materiel, such as nuclear fuel rods, to lumber on even for an extra year, and thus must shut down by the end of this year. The report argues that a short-term hike in coal-fired generation for the purposes of power generation (20 percent of Germany’s gas use) could be offset relatively easily by energy savings, shifting to electrical heating, and pushing harder and faster on clean energy expansion. Leopoldina argues that Germany’s 2030 exit date for coal could still be met.

In Germany, coal no longer generates heat, as it once did in communist East Germany, and thus couldn’t do much in the short-term to replace the gas generation that homes and factories rely upon. This means that demand is going to have to be curtailed – and industry is first in line for cuts, not families, says Schlögl.

“The steel and chemical sectors, which are very energy intensive, will have a massive problem,” says Schlögl. “But having an economic problem is one thing, war is another. There’s actually a clear choice. First we have to end the bloodshed and then we can repair the economy. This would send a direct message to Putin that we are entirely serious about going off fossil fuels.”

According to a recent YouGov poll, the majority of Germans would support a boycott of Russian oil and gas, with 54 percent of respondents saying they were strongly or somewhat in favor.