Energy communities have existed in the European Union (EU) for decades, yet they have been long overlooked as a way to ease the energy transition. Increasingly aware of their potential for socio-cultural and economic change, the EU is exploring these communities as key players in the energy transition. But more effort is needed to elevate them to forming a viable alternative. Teo Bierens and Anastasia Skapoula have the details.

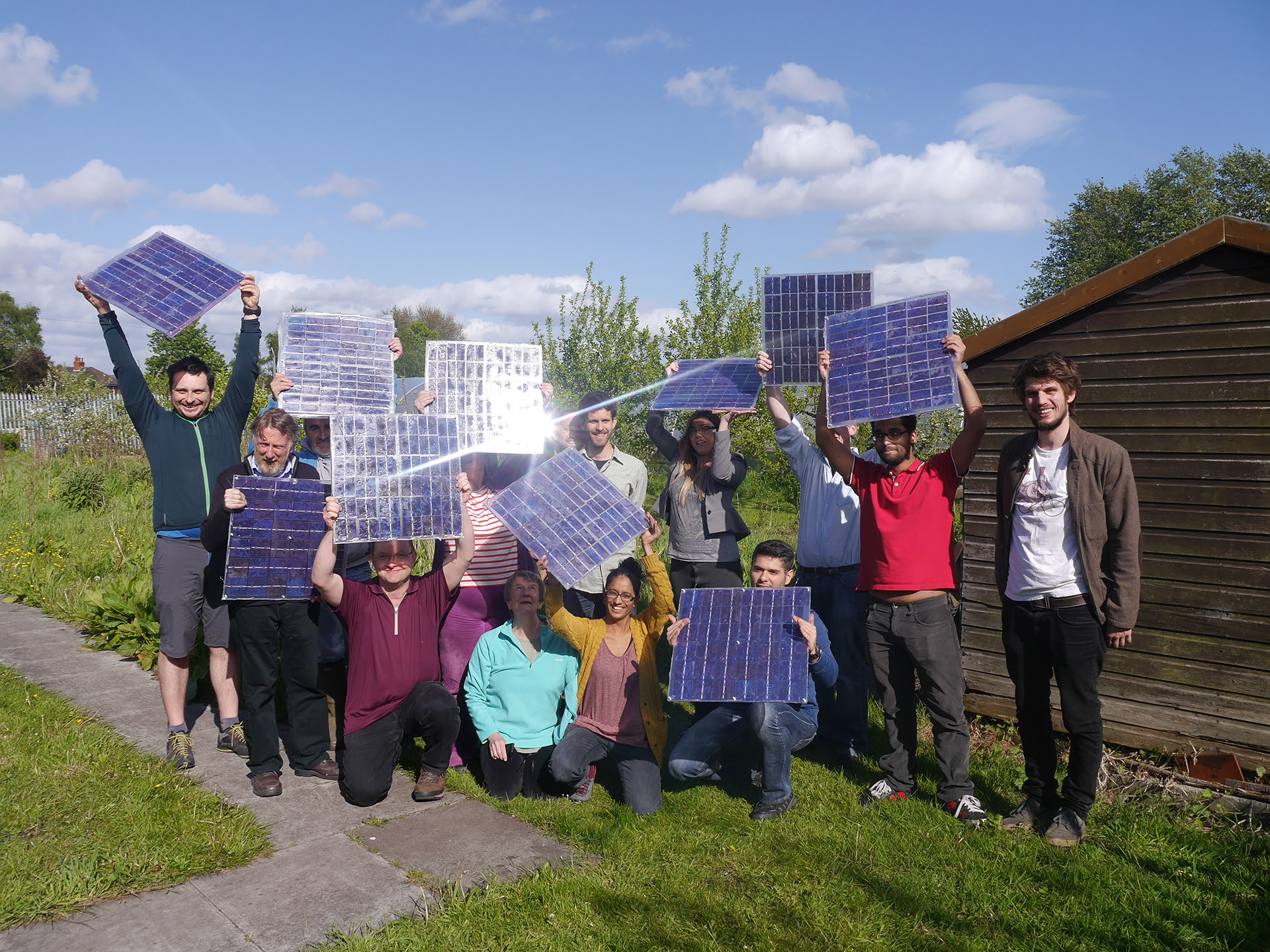

Energy Communities: grassroot initiatives for energy transition. (CC BY 2.0, 10 10)

The EU’s climate target for 2030 is to reduce greenhouse gas emission by a minimum of net. 55% compared to 1990 levels. This target supports the EU Green Deal objective for climate neutrality by 2050. The energy transition will shake up European Union’s economy and society, especially in carbon-intensive economies. With a view to making the transition cohesive and socially just, the EU has established the Just Transition Mechanism (JTM).

The JTM aims at mobilizing at least €150 billion during the period 2021-2027 in the most affected regions and consists of three pillars: First, the Just Transition Fund (JTF), which is an EU funding tool for regions dependent on fossil fuels and high-emission industries. Second, InvestEU provides funding for a wider range of investments, such as energy and transportation infrastructure, digitalization and digital connectivity, and circular economy investments. Third, the Public Loan Facility, will essentially support public investments by offering preferential loaning conditions to those areas most effected by the transition. Even though the JTM is aimed at compensating for both economic and social implications of the energy transition, the social aspect of the transition seems insufficiently addressed since it lacks an important component, the development of a sustainability culture. According to UNESCO, culture has been identified as an enabler for sustainable development, underscoring its importance for the JTM to incorporate this factor in its strategy.

Energy communities, collective grassroots initiatives that, for example, invest in the clean-energy infrastructure, are one way of promoting a sustainability culture and furthering the energy transition. This decentralized form of energy production provides energy to its local community and can be developed into different types of legal entities, among which cooperatives are regarded as the optimal choice, since they promote the advancement of energy democracy.

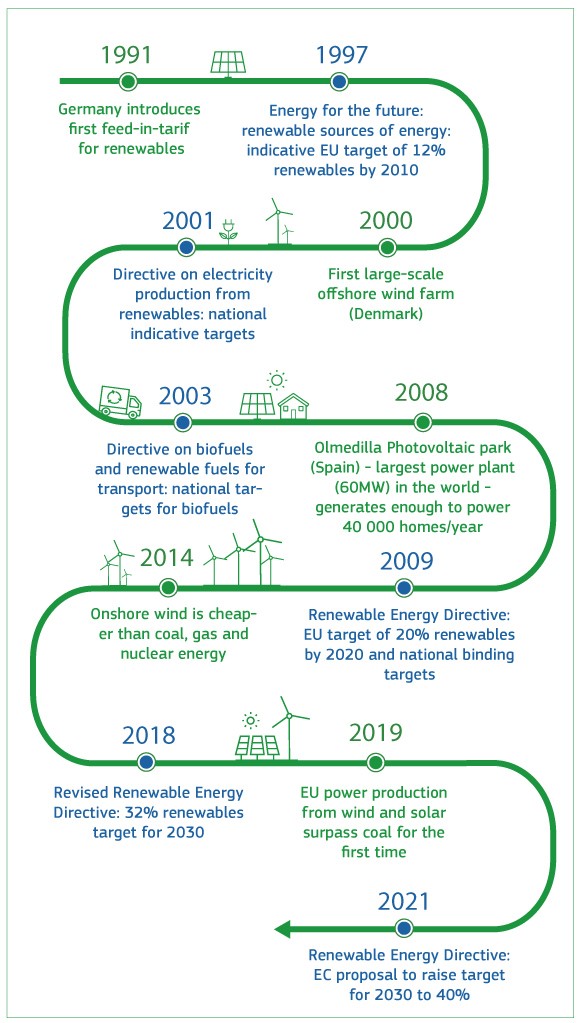

Figure 1. Timeline Renewable Energy in the EU

Emerging in the 1980s, these energy communities have existed for decades on the European continent. Today, over 1,900 projects exist across the EU involving over 1,250,000 EU citizens. Leading examples can be found in many countries including Sifnos in Greece, Hvide Sande in Denmark, and Ecco in Belgium.

In 2019, as part of Horizon 2020, the EU began developing a policy framework to foster the operation of these energy communities. A task force was set up and a policy document was published, defining the energy communities in legal terms. This document made the distinction between Renewable Energy Communities (REC) and Citizen Energy Communities (CEC), specifying that the latter cannot sell its produced energy.

The European Commission estimates that by 2030 citizen-led energy communities could own up to 17% of wind power and 21% of solar power. These developments illustrate that the EU sees the value of the RECs and CECs within the broader energy transition. Energy communities were only given a legal definition in the EU in 2019, 40 years after their emergence, illustrating a long history of neglect. Consequently, they are underdeveloped, and roadblocks remain in place hindering their development. The Renewables Networking Platform, established with the support of the EU, mapped out the obstacles preventing energy communities from fully developing within each separate EU Member State. Most of these obstacles are political and economic, while others concern grid regulation. At the same time, administrative and regulatory barriers, such as insufficient support schemes and legal recognition, hinder the development of the energy communities¹.

As part of the Fit-for-55 package, the European Commission proposed a revision of the Renewable Energy Directive (RED). With the adoption of the Renewable Energy Directive (RED I) in 2009, the EU had set itself an overall target of a 20% share of energy from renewable energy sources in the final energy consumption by 2020. It was substantially revised in 2018 (RED II), setting a new EU goal of a minimum 32% share of renewables in final energy consumption by 2030. RED III aims to create a more integrated energy market, thereby also making space for the energy communities both on the grid and on the market. The JTM should work complementary to the 2021 revision of the RED, by financially supporting energy communities across Europe. According to REScoop, the European federation of citizen energy cooperatives, the EU is currently directly funding 14 projects for community energy. This number could be significantly higher by making space in the budget of the InvestEU pillar of the JTM to designate a set amount of funding to directly support numerous key energy communities across Europe.

The promotion of energy communities offers a host of benefits, promoting sustainable energy sources contributing to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. They also shift consumer-producer relations in the energy sector towards prosumption which according to research can boost sustainable culture. Lastly, they can spark further change towards sustainable living beyond energy. All of these advantages offer a compelling reason why energy communities should be promoted by the EU, propelling its energy-transition aspirations and helping slash carbon emissions.

Teo Bierens and Anastasia Skapoula both are students who adress the just transition issue.

¹ Sokołowski, M. M. (2020). Renewable and citizen energy communities in the European Union: how (not) to regulate community energy in national laws and policies. Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law, 38(3), 289-304.