Away from coal! The need to get out of coal is now clear for everyone. But do we need instead more piped gas and LNG – liquified natural gas? Andy Gheorghiu reports

Action against the construction of a liquified natural gas terminal in Brunsbüttel (Uwe Hiksch, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

It is obvious to anyone with a clear mind that we have to say goodbye to fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – if we are to have a chance to limit the global warming that threatens our existence. That is why, for example there has been a fierce debate about the phasing out of coal in Germany. According to a German Parliament decision, this is supposed to take place by 2038 – much too late, say environmental groups and the climate movement.

But at the same time, this long phase-out period is being misused to usher in a new era of fossil fuel use – that of fossil gas. This offers players in the fossil-fuel market the prospect of surviving well beyond 2050. The argument follows a distorted form of logic: we need gas as a substitute for coal so we can master the transition into the post-fossil-fuel era. Such a shame that we only have 10 to 30 years at most left for the transition. There is no more time to invest in new climate-unfriendly gas projects.

By 2035, the consumption of almost all fossil fuels (including fossil gas) throughout the EU will be incompatible with our climate change commitments. Germany, once celebrated as the home of the energy transition, is already failing miserably to meet its binding commitments to protect the climate.

But why? Fossil gas is a climate-friendly alternative to coal, isn’t it?

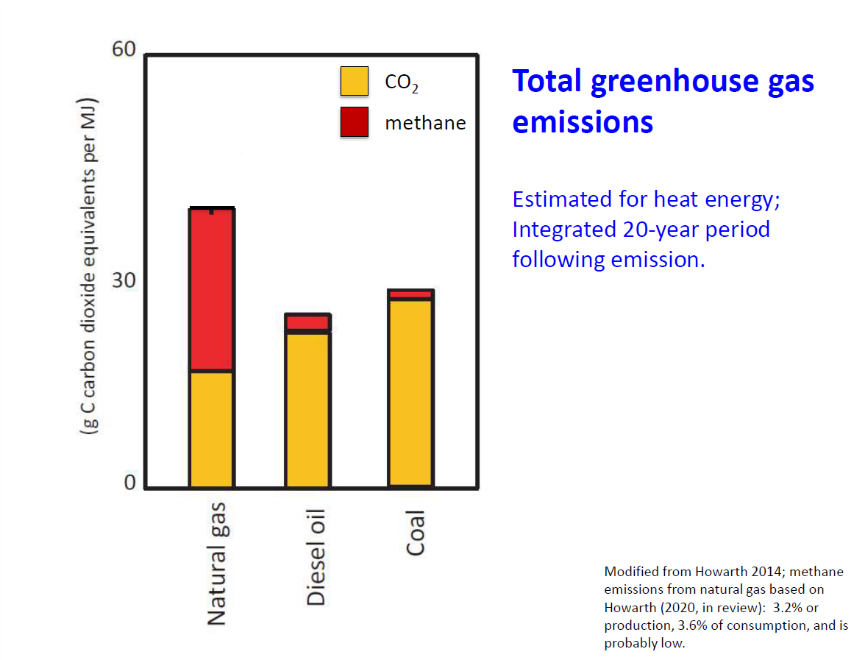

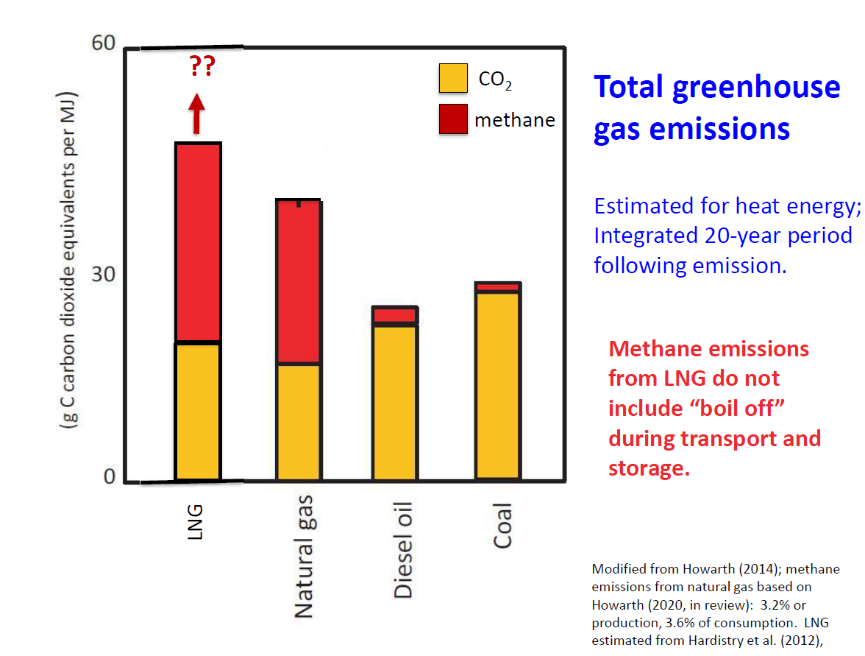

Fossil gas consists almost entirely of methane. The problem is that the methane that escapes into the atmosphere is far more damaging to the climate than CO2 (up to 87 times more in the first 20 years, falling to around 36 times after 100 years, according to 2013 figures from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC). In view of tipping points in the climate system, which may lead to irreversible climatic changes in the next 10 to 20 years, it is urgently recommended to use the current IPCC figures when doing climate assessments, and to take into account the extremely damaging effects of methane in the first 20 years.

Howarth (2020): “No room for natural gas in a climate-smart future”. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, invited contribution for a special issue on 100% renewable energy futures, in press, August 2020

Sadly, even today, supposed experts, such as those in the Federal Environment Agency, are still working with the 100-year value for methane – and even with an outdated greenhouse gas potential value of 25 for fossil gas. Whether deliberate or through ignorance, using these old figures dramatically dilutes the apparent impact of fossil gas. And what’s worse: Germany’s dependence on fossil gas prevents Germany and the EU as whole from achieving the climate targets set by the Paris Agreement and hinders attempts to curb global warming.

Germany is not only the biggest gas consumer in Europe, but also a major hub for gas trading. Germany has the capacity to import 54 billion m³ of gas a year from Norway, 208 billion m3 from Russia, and 25 million m³ from the Netherlands. Together with its storage capacity of 24.3 billion m³ – the largest in Europe and fourth largest worldwide – this capacity is over three times higher than Germany’s own annual gas consumption. The connection of Nord Stream 2 would boost an already over-inflated import capacity by another – unnecessary – 55 billion m³.

So, where is Germany headed?

1. Nord Stream 2

Despite justified criticism from the European Commission and several European states, along with US sanctions against Nord Stream 2, the German government sticks to its support for this Gazprom project, which would make Europe even more dependent on Russian gas. Investors in Nord Stream 2 include the German firm Wintershall DEA, the former German company Uniper (previously part of E.ON, now owned by the Finnish state), the French firm Engie (previously Gaz de France), the Anglo-Dutch Royal Dutch Shell, and the Austrian firm OMV.

It should be noted that the Russian Federation is the majority shareholder of Gazprom, with 50.23% of the shares. This makes Gazprom an instrument of Russian foreign policy. Energy sources (oil and gas) are Russia’s number-one export. The year 2019 saw Russia exporting energy sources worth €234.5 billion. The most important driver of growth in 2019 was the export of liquified natural gas, worth €6.67 billion. With a market share of 20%, Russia is the second-largest source of the EU’s LNG imports. Qatar is in top place, at 28%, while the USA is in third place with 16%. Fracked US gas accounts for around one-quarter of the LNG imports to Poland, the Netherlands and Portugal, while Russia supplies 51% of Dutch LNG imports. This is not surprising. The Rotterdam Gate Terminal stated in early 2018 that it aimed to become the main hub for Russian LNG, probably mainly to boost its poor capacity utilization rate. In August 2019, Russia even shipped LNG from the Yamal export terminal to Canada via the Dutch terminal. The operators of the Gate Terminal, Gasunie and Vopak, both Dutch firms, are also would-be investors in the LNG terminal in Brunsbüttel in Germany. But this terminal is supposed to help reduce dependence on Russian imports. Interesting…

An extract from a detailed analysis by the European Commission, Nord Stream 2 – Divide et Impera Again?, lists the major arguments against the Nord Stream 2 project:

Nord Stream 2, seen from a common EU perspective, is a project with neither economic rationale nor political backing. It would cost billions of euros that could be spent in other priority segments of the economy and the energy sector. Its economic rationale ignores EU objectives on energy efficiency (that will also diminish gas demand); renewables (heat sources and biogas); and research and innovation (the potential future technological breakthrough on electricity storage and/or power-to-gas would further slash post-2030 EU gas imports).

The German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) is also clear in its analysis of the fact that another Baltic pipeline is superfluous. DIW draws attention to the following:

- The planned second Baltic Sea pipeline Nord Stream 2 is not necessary to secure the fossil gas supplies of Germany and Europe.

- The economic calculations used to justify the pipeline rely on outdated assumptions about the development of demand for gas.

- The supply of gas is already well-diversified.

Environmental Action Germany (Deutsche Umwelthilfe) is now taking legal action against Nord Stream 2 and wants a legally enforced review of the operating permit. Its main argument: new scientific evidence confirms that methane emissions have a massively negative impact on the climate, so that the operation of Nord Stream 2 would thwart the climate target.

Germany’s stubborn attitude in favour of Nord Stream 2 contributes to the further division of Europe, fuels the increasing transatlantic geopolitical tensions, and creates senseless debates about the construction of similarly unnecessary climate-damaging LNG terminals in northern Germany. These are supposed to be supplied mainly with climate-hostile fracked gas from the United States. The common argument is that LNG will help diversify away from Russian gas.

An inquiry by German parliamentarians in October 2018 revealed that the German government had already supported Yamal LNG to the tune of €200 million in the form of export credit guarantees – a step that does not fit the supposed attempts to achieve independence from Russian gas.

As if this were not enough, in 2018 the same German government gave a guarantee for untied loans of €1.2 billion for the biggest competitor to Nord Stream 2, the so-called Southern Gas Corridor. The argument is well known: this will help diversify away from Russian gas.

Welcome to the crazy world of the gas market.

2. LNG terminals up north

Liquefied natural gas

To transport natural gas by ship rather than pipeline, it must first be liquefied by cooling it to –162°C. Since liquefied natural gas releases less CO2 than oil or coal when burned, many politicians and businesspeople celebrate it as a “bridging technology” for the coming decades. The cooling and liquefaction of the gas consumes a lot of energy (between 10 and 25% of its fuel value), so its apparent CO2 advantage quickly disappears or even turns negative. If the climate effects of fossil gas and methane losses during the entire production cycle are taken into account, then LNG, and especially fracked gas, have an even worse climate balance than coal.

Sources: Energie-Lexikon, Bundestag, DW, DVZ, Other useful sources: howarthlab.org

Even disregarding all the climate and environmental aspects, investments in new fossil infrastructure with an expected lifespan of at least 30–50 years make absolutely no sense. This is especially true of the planned LNG terminals in Brunsbüttel in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein, and Wilhelmshaven and Stade in Lower Saxony. Instead of allowing the much-lauded market to “simply do its thing”, various investors are reliant on blind (because ignorant and fact-denying) political support as well as direct and indirect subsidies.

Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, market analysts repeatedly pointed out that Germany plans to pump millions of euros into big LNG projects for which there is hardly any demand, thereby creating stranded assets with taxpayers’ money. The pandemic is now relentlessly revealing what was clearly foreseeable: the LNG bubble is about to burst.

The EU’s (including the UK’s) overall LNG import capacity is already enough to meet 45% of its current total gas needs. On top of that, the terminals have a poor average utilization rate. My calculations (based on data from Gas Infrastructure Europe) reveal an average capacity utilization rate of around 24% for the period January 2012 to March 2019. According to “Finding a home for global LNG in Europe”, an analysis paper published in January 2020 by the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, the utilization rate of all LNG terminals in 2012–17 was only about 20% of LNG re-gasification capacities.. The year 2018 saw a slight increase to 27%. Only 2019 stands out, with a utilization rate of 48%, probably due to a huge increase in US LNG exports to the EU.

According to the EU Commission, American LNG exports to Europe rose by almost 600% between July 2018 and November 2019. The background to this is the so-called Trump–Juncker deal of 2018. At its core is horse-trading that is as simple as it is frightening: the USA promised to levy no taxes on the European steel and car industries, and in return the EU will buy unnecessary, climate-hostile and environmentally destructive US fracked gas.

This is how the honest answer by Germany’s Economy Minister Peter Altmaier at the start of the LNG debate can be explained. In a September 2018 meeting with Maroš Šefčovič, the vice-president of the European Commission, Mr Altmaier openly admitted that the decision in favour of LNG terminals in Germany should primarily be seen as a gesture towards the US government.

Just a few months later, in February 2019, Mr Altmaier – along with Dan Brouilette, the American Deputy Secretary of Energy, and Fatih Brihol, Executive Director of the International Energy Agency – hosted a German–American conference on the development of the LNG import market. The participants included the German Association of Energy and Water Industries (BDEW), the Center for Liquefied Natural Gas (CLNG, the biggest US LNG lobbying association) and LNG Allies (a group that promotes US LNG exports). As a preliminary result of the conference, Mr Altmaier presented a key issues paper proposing changes in the German legal framework in favour of LNG infrastructure projects in Germany. “On this basis, the costs of pipeline construction can be refinanced without delay through gas network charges and passed on to network users”, the paper states. Or in plain English: gas customers, and not investors, will have to cover the costs.

Just nine months later, the corresponding LNG Regulation was announced. Environmental groups and civil society organizations – who learned only by chance that the draft would be published on Thursday, 14 March 2019 – were given a laughably short notice to comment by Tuesday, 19 March at 3 pm. Despite this, an alliance of 25 organizations against LNG presented a position paper before the deadline. Their arguments were completely ignored. The movement against fracking and LNG hoped that the German states where the Greens were part of the government would withhold approval in the upper house of the German parliament. These hopes were dashed. On 7 June 2019, six of the nine states co-governed by the Greens voted for the regulation – even though they could have defeated it merely by abstaining.

That exempted the LNG terminal operators of 90% of the costs of building and operating the connecting pipelines for the terminals. Only a few months previously, the Federal Network Agency, the regulator in charge of electricity, gas and other networks, had removed the connecting pipeline to the planned LNG terminal in Brunsbüttel from the gas network development plan in order to “protect gas customers from unnecessary costs”, because the “construction of the connections is the responsibility of the terminal developers”.

To put this in figures: for the Brunsbüttel LNG terminal in Schleswig-Holstein, the investor, German LNG, was exempted from costs of at least €78.3 million for the construction of a pipeline connection, and from €700,000 a year for the operating costs. But these are just the indirect subsidies that the operator wants to obtain. In addition, the government of Schleswig-Holstein has already earmarked €50 million in direct subsidies in its 2020 budget. If the funds are actually disbursed, they would attract a matching subsidy from the federal government of another €50 million because they fall under the rubric “Joint responsibility for the improvement of regional economic structure”. For an estimated total investment of around €450 million, a tidy 22% would come from public funding – in addition to the relief for the construction and operation of the pipeline connections.

The partisan state aid for the planned LNG terminals in Wilhelmshaven and Stade comes in the form of the Lower Saxony LNG Agency (LNG Agentur Niedersachsen), which is also supported as a project of the Federal Ministry of Economics and Energy and the State of Lower Saxony under the “Joint responsibility for the improvement of regional economic structure”. The goals of this agency include support for developing the LNG infrastructure on the Lower Saxony coast, support for LNG technology as a “climate-friendly” energy supply and fuel for ships, and the positioning of the Lower Saxony coast as an LNG region. Dialogue with opponents is not only not sought; it is also actively avoided. An example of this was the one-sided online launch event on 18 June 2020. Critical comments were ignored or dismissed as half-truths, and the public online chat with critical questions was closed without further ado. Despite statements to the contrary, discussion with environmental groups has still failed to materialize.

| LNG Terminal | Brunsbüttel | Wilhelmshaven | Stade |

| Regasification capacity | Up to 8 billion m3/year | Up to 10 billion m3/year | Up to 8 billion m3/year |

| Investment costs, terminal | €450 million | €300–450 million | €850 million |

| Construction and operating costs, connections | Estimated by investors at €87 million for connections and according to estimates by the German Economy Ministry, ca. €700,000 annual operating costs | According to a response by the German federal government, estimated at €86 million for connections and €690,000 annual operating costs | According to a response by the German federal government, estimated at €30.5 million for connections and €245,000 annual operating costs |

| Investor | German LNG (Gasunie, Oiltanking, Vopak) | Uniper

Mitsui O.S.K. Lines (MOL) |

Dow Chemical

Macquarie Group China Harbour |

| Regasification capacity partner | RWE | ExxonMobil | No partner yet |

All rights reserved

3. Opposition

Despite policymakers’ disregard for arguments backed up by credible sources, and in spite of the many hurdles placed in its way, resistance is growing. The climate alliance against LNG, a grouping of many different organizations, with the strong support of German Environmental Action, has managed to ensure that the investors have not been able to realize the deadlines they had set.

German LNG was forced to ask the city of Brunsbüttel for a two-year extension until June 2022 for the final investment decision. German LNG originally wanted to reach such a decision by the end of 2019; construction was supposed to begin in 2020 and operations were expected to start in 2022.

In Wilhelmshaven, where activists most recently organized a demonstration against the terminal in mid-July 2020, concern for protected habitats overturned the already controversial project. Uniper, which had over-hastily signed a contract to construct and charter an LNG terminal ship even though it did not have the necessary permits, has had to seek a new location. Plans to bring the facility into operation in the second half of 2022 are probably now off the table.

As far as Stade is concerned, plans lag far behind those in Brunsbüttel and Wilhelmshaven. According to the official timetable, the LNG terminal is supposed to be operational by 2024.

4. The myth of hydrogen and biogas

Just looking at the expected economic lifespan of 30–50 years, it quickly becomes obvious that in reality there is no time left for investments in LNG terminals or the Nord Stream 2 pipeline. After all, the phase-out of fossil fuels would have to start immediately after the facilities come into operation. However, there are no concrete or detailed plans on how or when this is supposed to take place.

Instead, promises have recently been made that existing fossil gas infrastructure can later be used for hydrogen or biogas. Such promises quickly crumble in face of technical difficulties and the questionable sustainability of such alternative energy sources.

First, hydrogen would only be truly climate-friendly if it were produced 100% with solar or wind energy. But according to the International Renewable Energy Agency, 95% of the hydrogen currently available worldwide is made from coal or natural gas, and 5% comes as a by-product of chlorine production. Significant production of hydrogen based on renewable energy does not yet exist. It is therefore important to classify the “climate friendliness” of hydrogen based on how it is actually produced.

Second, hydrogen may be fed into the existing German gas grid at concentrations of only up to 5%. Using 100% pure hydrogen in the fossil gas network would require a completely new (or totally upgraded) infrastructure. Fossil LNG terminals are by no means suitable for storing hydrogen.

Third, according to the German Association of Energy and Water Industries, up to 10.3 billion m3 of biogas could be fed into the German gas network each year by 2030. By 2050, a total potential of some 25.75 billion m3 is being forecasted. That is not nearly enough to meet the annual demand of 90 billion m3, or even to supply the existing gas infrastructure (without counting Nord Stream 2 and the planned LNG terminals). Where is all this biogas supposed to come from, if not from even more intensive monocultures of energy crops such as maize, or yet more intensive industrial animal raising (and the concomitant lakes of manure slurry)? For bio-LNG, the equation is even crazier: first the biogas must be produced, and then converted to LNG with the inevitable loss of 10–25% of the energy value. Huge amounts of land would be needed. This would certainly depend on farmland in the Global South – with massive negative consequences for food production and the economic structures there.

And this is supposed to be the climate-friendly, green alternative?

One quickly realizes the truth: sustainable feeding of fossil infrastructure with climate-friendly hydrogen or bio-LNG is an attractive myth that does not stand up to closer scrutiny.

What remains is the recognition that things indeed have to change radically if we want to avoid even stronger geopolitical tensions and more drastic global warming. The question is not so much whether we wish to do so. We have no choice – we must push for change with all the means at our disposal. If we fail to do so, there will only be losers.

For Germany this means that both Nord Stream 2 and the planned LNG terminals are a stupid waste of precious money and energy, which would catapult us into a global warming scenario (probably) far over 2°C. It would be both prudent and wise to invest those resources more efficiently into the process of finding true alternatives and prospects for the future.

But be snappy about it! There is no time to waste!