After twenty years of negotiations, the European Union is in the process of advancing one of the world’s largest free trade agreements with four states of Mercosur. The planned agreement suggests a political path that veers towards a worsening of the international climate crisis. Kathrin Meyer discusses the questionable contents of the political act, which will solidify inequality amongst the trade partners and enable the expansion of environmentally harmful methods.

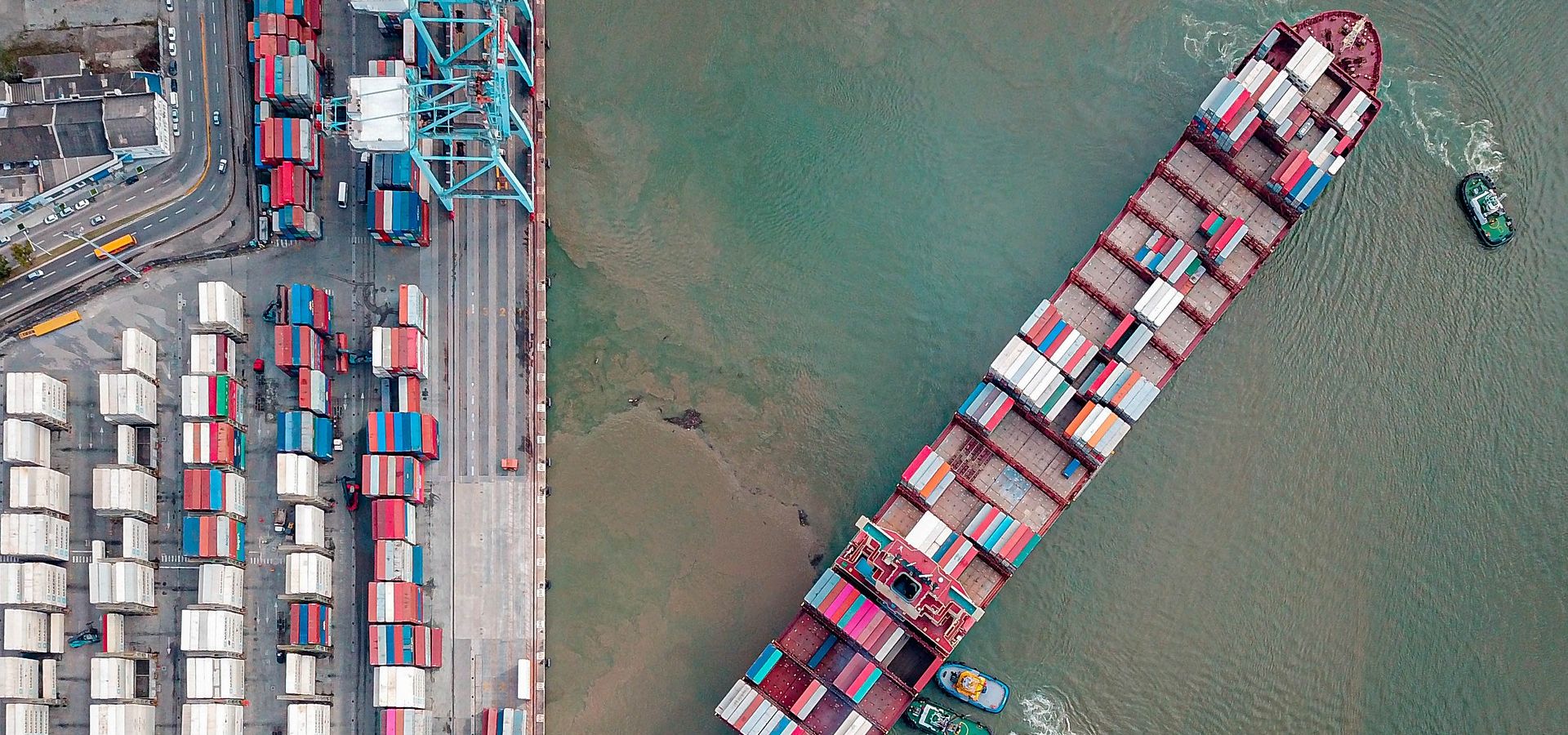

The origin of some of the traded goods is ecologically and socially unacceptable (Public Domain)

With disregard to both the current international declarations on the worldwide climate crisis, as well as the exploitation and degradation of ecosystems outside of the European continent, the EU continues to ensure its needed raw material supply in order to encourage the expansion of its industrial sectors.

Such contempt is reflected in the current free trade agreement between the EU and the Mercosur countries, Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. The process to build one of the largest free trade areas in the world was launched on June 28th, when the EU Commission called on its member states to ratify the detailed agreement.

EU Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström defended the initiative despite critical voices from climate activists and farmers, who condemned the ongoing negotiations on the biggest free trade agreement between the European Union and Mercosur countries. In an interview with the daily newspaper Die Welt, she rejected possible changes within the agreement and said: “The treaty is ready and on the table. What’s done is done [sic!]”.

Justified criticism

Trade relations between Mercosur countries and the EU are already considered unequal. International NGOs and institutions fear that the ratification of the negotiated treaty could further strengthen structural problems.

A report by the non-profit organisation Misereor shows that the energy and raw materials sector will be one of the areas most affected. In addition to the further development of environmentally harmful processes, such as deforestation of the Amazon and new projects to promote fossil fuels, the abuse of labour will also intensify. A chief example of this includes the poor working conditions in the field of raw materials extraction.

Although the past few months have borne witness to growing environmental movements and demands for environmentally friendly political action, the focus of the free trade plan is certainly not about advancing the international energy transition. The agreement does not provide any incentives for decentralized renewable energies. On the contrary, the focus continues to be on existing production and supply models, which will continue to persist despite environmentally logical – and preferable – alternatives.

Existing production and supply models describe, inter alia, the continuation of the export relationship regarding mining products and further extraction plans.

Abolition of important export taxes

In the past, the Mercosur states regulated the export of products like lithium, copper and iron pre, due to environmental concerns, the security of their own commodity supply, and the protection of the national labour force. This will change with the new EU Trade Agreement, as the main goal of the EU’s negotiations consists of the prevention of such export restrictions to secure the supply of raw materials.

Furthermore, a ban on export taxes should make the purchase of raw materials from Latin American countries cheaper for the EU. This could mean a sharp drop in revenues for trade partner Argentina, which uses export tariffs to promote national social programs.

Liberalization at all costs

To further the development of infrastructure within the fossil fuel and mining sectors, the EU has pushed to expand the liberalization of the local energy and commodity sectors for investment and services, including continued extraction projects like the drilling for deep-sea oil deposits in Brazil or the investments in the exploitation of shale gas deposits in Argentina. The construction and building of new power plans, as well as pipelines, are on the EU’s trading agenda.

So far, not all EU member states have agreed to the fatal agreement. France has declared that it will not ratify the treaty as long as there are no valid guarantees, like the protection of the Amazon and French agriculture, as European agriculture is also at stake.

In response to French demands, political representatives from Germany, Spain, the Czech Republic, Sweden, Latvia and Portugal have sent a letter to the European Commission calling for a rapid procedure to ensure enforcement of “one of the most important agreements in the common European commercial history“.

This is partly because of the political situation in Argentina, where President Mauricio Macri could possibly be unseated by the coming election at the end of the year. It is worth considering if the political agenda of the Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who is known as a despiser of the environment and human rights, could have contributed to the constitution of the letter. Bolsonaro appears poised to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, which would make the process of ratifying the treaty more difficult for the EU.

From the European side, one could argue that Angela Merkel and the other co-authors have lost sight of the path of sustainability for which they claim to be fighting.

Perhaps there should be stronger calls for a review of the trading agreement, which appears to have calcified in outdated ideals over the course of the last twenty years of negotiations. The demands of the European Union in this historic agreement, which include further extraction plans, expended claims of ownership, and contempt for the lands and quality of life of non-European people, reflect a neo-colonial approach in which sustainable policies are not to be found. As a result, the international climate crisis seems likely to brew into a climate disaster.