The EU has introduced a new measure to decrease aviation emissions, which is called CORSIA. But it’s not strong enough to protect the climate, say Mareike Willems and Christoph Störmer.

Will CORSIA water down the ambition of the EU climate policy? (Public Domain)

Aviation is responsible for 2% of global CO2 emissions and could consume a quarter of the world’s carbon budget by 2050 in a 1.5°C scenario if the sector’s rapid growth continues. Therefore, an effective mechanism to reduce the sector’s emissions is crucial to global climate change mitigation.

The EU attempted to regulate aviation sector emissions in the cap & trade EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) in 2008. The cap was thereby set as the equivalent to 95% of the historical emissions between 2004 – 2006. However, flights that take off or land outside the EEA are exempted by the ‘stop the clock’ decision until a new strategy reflecting the outcomes of the CORSIA agreement is found.

The New Global Market Based Measure – CORSIA

The Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) was adopted in October 2016. One of its main goals is to achieve carbon neutral growth from 2020, which means to keep global net emissions of aviation from 2020 on at the same level.

In contrast to the EU ETS, CORSIA is designed as an offset mechanism and basically relies on (1) its CO2 baseline and (2) on the quality of the offsets. It is argued that CORSIA does not have the same effectiveness in terms of climate mitigation compared to the EU-ETS.

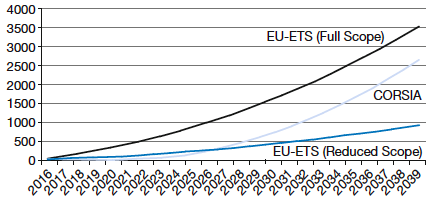

For example, the 2020 baseline of the CORSIA agreement will leave all prior emissions unregulated and is therefore not ambitious enough. But because of its larger, global scope, the predicted cumulative CO2 mitigation of CORSIA will exceed the amount of the predicted reduced EU-ETS mitigation by 2027. For the time being, the EU-ETS does not regulate international aviation emissions due to the so-called ‘stop the clock’ decision. If it returns to its original state, the cumulative amount of CO2 mitigation that could be reached, would not be exceeded by CORSIA at least until 2039.

To reach its mitigation goals, it is necessary that the offsets are environmentally friendly. But this will most likely not be the case, if for example the offset projects are supplied by the UNFCCCs offset mechanism CDM or by its future successor, the SDM, for which the exact rules have not yet been decided.

Besides offsetting, airline companies can also use ‘sustainable alternative jet fuels’ to lower their emissions. But there are two substantial problems with the inclusion of bio-fuels in CORSIA. First, the development and purchase of alternative fuels is currently far more expensive than buying offsets. If CDM offsets are to be accepted for CORSIA (with current prices around $1/CO2te), it would not make economic sense for airlines to invest in cleaner fuels or research for higher energy efficiency. As we already know, biofuels are not necessarily environmentally friendly, due the use of huge territories of land that could be affected by land-grabbing and loss of biodiversity.

Apart from its strategic shortcomings, the lack of transparency in the negotiations, as well as its the huge influence of aviation industry lobbyists in the decision-making process is also criticized.

Implications for European Aviation

Following ICAO resolution A39-3, CORSIA is planned to be the only existing global instrument regulating emissions of international aviation. This might lead to replacing the EU-ETS mechanism for aviation with the much weaker CORSIA scheme.

The proposed strategy met strong opposition in Brussels. In October the European Parliament issued a resolution opposing “the efforts to impose CORSIA on flights within Europe, overriding EU laws and independence in decision-making”. France, the Netherlands, Portugal, Belgium, Austria, Finland and Norway already threatened independently to withdraw from the agreement if any more environmental standards would be further weakened.

Waving Goodbye to Carbon Neutral Growth

CORSIA would undoubtedly water down the ambition of EU climate policy. It is important for the EU to leave all possibilities reserved for its own legislation aviation within the European Economic Area (EEA). Of course the EU-ETS need to be fixed. But if fully replaced by the UN agreement, the EU could lose its only instrument to reduce aviation emissions in the EEA and diminish its leverage in shaping international regulations in this sector. Nonetheless, it is essential for the European Union to ensure the integrity of CORSIA if it aspires to remain a front-runner in international climate policy.

Even if EU-ETS and CORSIA would be implemented simultaneously, the projected reduced emissions would still not be enough to meet Paris Agreement climate goals. Furthermore, CORSIA does not address significant other greenhouse gases from aviation such as NOx and water vapor.

CORSIAs reliance on controversial offsets and biofuels will not bring about the necessary achievements to limit global warming to 2°. The more direct solutions, such as the introduction of taxation for aviation fuels and a tax on airlines tickets, have been impeded so far. CORSIA does not represent a sign for relief yet, and far more ambitious instruments need to be developed.

Mareike Willems is a student of “Europeanstudies” at the University of Bremen, Germany, where she focuses on European and climate politics. After finishing her internship at the Heinrich Boell Foundation European Union, she continued working for “the greenwerk “(climate advisory network).

Christoph Störmer studied ‘Governance and Public Policy’ at Passau University where he focused on global governance and climate justice. He was a trainee at Heinrich Boell Foundation European Union at the climate and energy programme.