Localized energy systems are more resilient than a traditional grid, and offer solutions to power outages around the world. Ben Paulos takes a look at microgrids, minigrids, and how Puerto Rico could get to 100% renewable energy.

Power remains cut off in areas of Puerto Rico, months after Hurricane Maria ravaged the island (Photo by Waldemar Rivera, Public Domain)

Extensive damage to the Puerto Rico power grid has underscored the vulnerability of wires strung on wooden poles, connecting distant power plants to customers.

Since this is a standard feature of the twentieth-century power grid, systems all around the world are subject to outages. Fires in California, floods in Houston, sandstorms in Africa, and ice in cold climates are just a few of the many factors that can knock out power.

A solution emerging from the crucible of the long outage in Puerto Rico is the minigrid. New distributed-energy technologies like solar panels, battery-storage systems, and smart controls enable customers to provide services to the grid when things are running normally and separate from the grid if there is a broad outage.

Many Grids

First, it’s important to grasp the taxonomy of this emerging field. Microgrids are typically sized on the scale of a complex of buildings, like a college campus or a military base. Minigrids are larger, able to serve a village or a small city. Nanogrids are smaller, limited to a single building or load.

By dividing the grid into parts that can be independent if necessary, engineers hope to create greater resilience to damage or attacks on the power system.

Speaking on Greentech Media‘s Interchange podcast, Chris Shelton, chief technology officer of AES Corporation, an international energy company, describes AES’s concept for a rebuild of the Puerto Rican power system.

AES was responding to requests from the Puerto Rico Energy Commission for new approaches to restoring their power system.

“They wanted to hear transformative ideas from stakeholders,” said Shelton. The AES team spent 10 days locked in a room, developing a minigrid vision “with some surprising outcomes.”

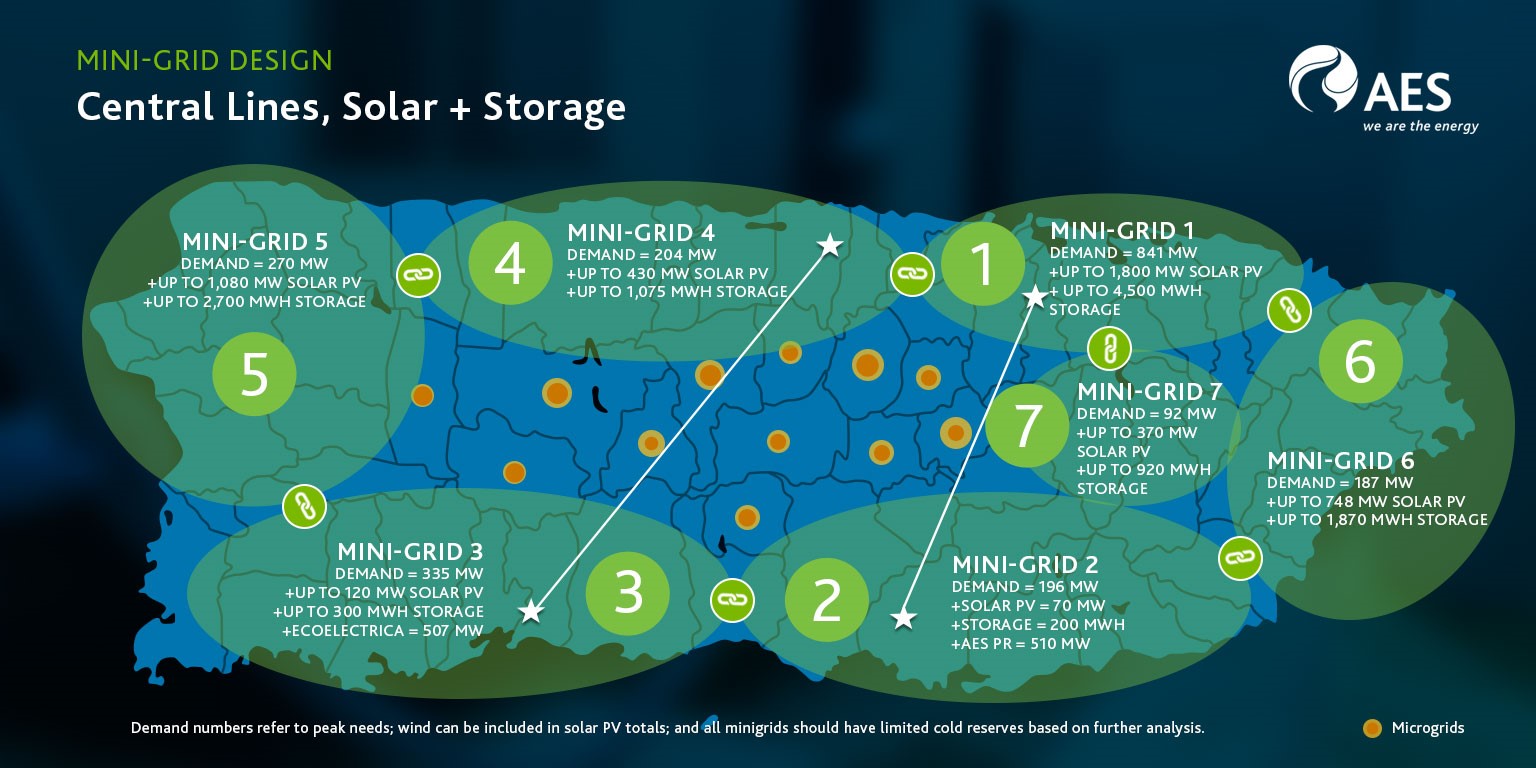

The AES vision is a series of seven solar-plus-storage minigrids that ring the island. They would be connected with weather-hardened transmission lines, and would operate as a single system under normal circumstances, but could run independently if needed.

The result is a hybrid of a traditional centralized system and a fully distributed system. Shelton thinks both of those options have weaknesses. First, it’s hard to make a centralized system impervious to damage, he argues, and loss of any key part can cripple the whole system. The other extreme, all distributed energy, would also make it difficult to recover from an outage, due to the many individual devices that would have to be coordinated.

As shown in the map below, rural customers in the interior would be served with microgrids, eliminating the need for distribution grids meshing the rugged mountains.

Paying for Resilience

The key criteria for the AES team was to reduce fuel costs and inefficiency. Much generation on the island currently comes from oil burned in steam generators, “which is not an efficient combination,” according to Shelton. Electricity rates on Puerto Rico are the second highest in US regions, behind Hawaii.

Hawaii’s very high energy costs, also due to the state’s dependence on oil, have been the key driver in the Hawaiian Electric Companies’ push for a 100-percent renewable system. They will be a key driver in Puerto Rico as well.

“When you do the comparison, solar is the least-cost way to get energy onto the island, and maybe a decent amount of wind as well,” says Shelton.

“The fuel cost [savings] is a way to pay for the resiliency,” he says. “We estimate that a very large amount of solar and storage would be funded by avoiding fuel costs for 10 years.”

“To eliminate the fuel cost, you have to bring that [same amount of] energy onto the island.” The island would need 10,000 MW of solar to capture enough to meet current energy demand, which peaks at around 3,000 MW.

“The next thing you have to figure out is how we can actually use it,” he says. About 2,500 MW of 10-hour duration storage, combined with 1,000 MW of existing conventional generators to fill in the gaps should be sufficient.

“Plus, the grid itself can be very valuable,” Shelton says. The existing grid “serves as the core of the autonomous minigrids that are then interconnected into a larger system.”

Under the AES plan, most existing oil and gas power plants would be moved into “cold reserve,” to be available for the infrequent times when the primary solar and storage systems are inadequate. These plants are already built, but are expensive to run.

“Informing the state of the art today—what’s possible with today’s solutions, and at what cost—is critical at this time,” Shelton says.

And the timing is right. Gov. Richard Rossello announced plans on January 22 to begin the process of privatizing the government-owned utility, PREPA. Noel Zamot, the coordinator tasked by the Federal Oversight & Management Board for Puerto Rico with revitalizing the island’s critical infrastructure, sees the opportunity for tremendous change.

“The average consumer in Puerto Rico now speaks of ‘renewables,’ ‘microgrids,’ ‘distributed generation,’ and ‘grid resiliency’ with ease,” he wrote on Medium. “Two days after Hurricane Maria, only pundits were having lofty discussions regarding the future of Puerto Rico’s energy strategy. Now everyone on the island is asking ‘Why Not?'”

“Public entities now know that everything is on the table,” Zamot says.

[…] Puerto Rico disaster opens the door to distributed energy by Ben Paulos, Energy Transition blog […]