The results of the most comprehensive survey of what the Germans think of their energy transition were published in November. Craig Morris says the researchers themselves were surprised by some of the findings.

Energy transition now: Germans overwhelmingly support renewables (Photo by Molgreen, edited, CC BY-SA 3.0)

There have been many studies on the Energiewende, so it came as some surprise to hear Ortwin Renn, head of the Institute of Advanced Sustainability (IASS), say that the new Social Sustainability Barometer “measures, for the first time, how just Germans think the Energiewende is” (in German). Daniela Setton, who headed the project for the IASS, admits that previous surveys have asked such questions, “but ours is the first comprehensive one done with scientific rigor.”

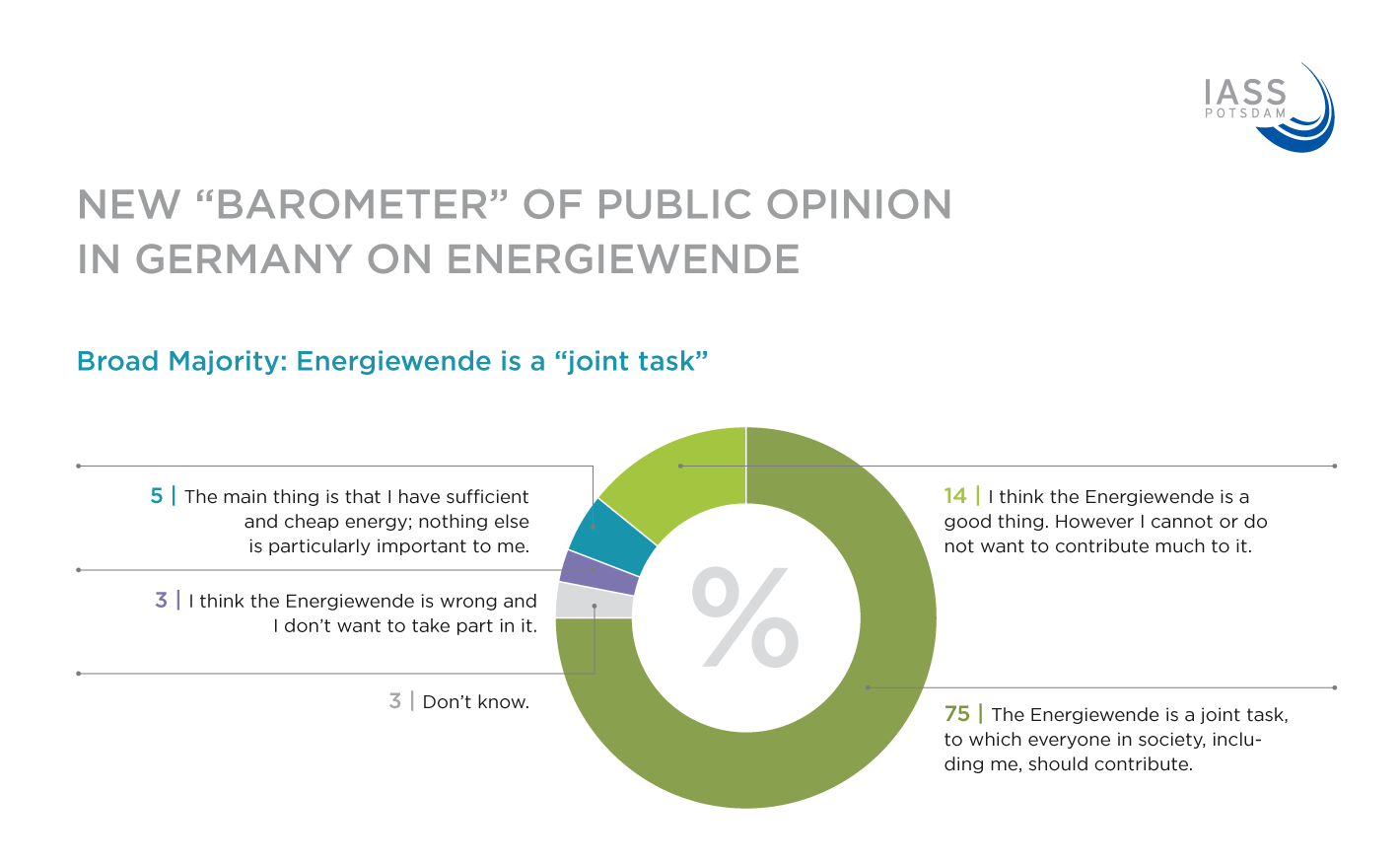

It also carefully worded previously posed questions to elicit responses more clearly pertaining to fairness. For instance, the old question of “Energiewende: good or bad” was asked (thumbs up by 89% of those surveyed), but the responses were not just categories like “agree” and “strongly agree.” Rather, here’s what respondents could choose from:

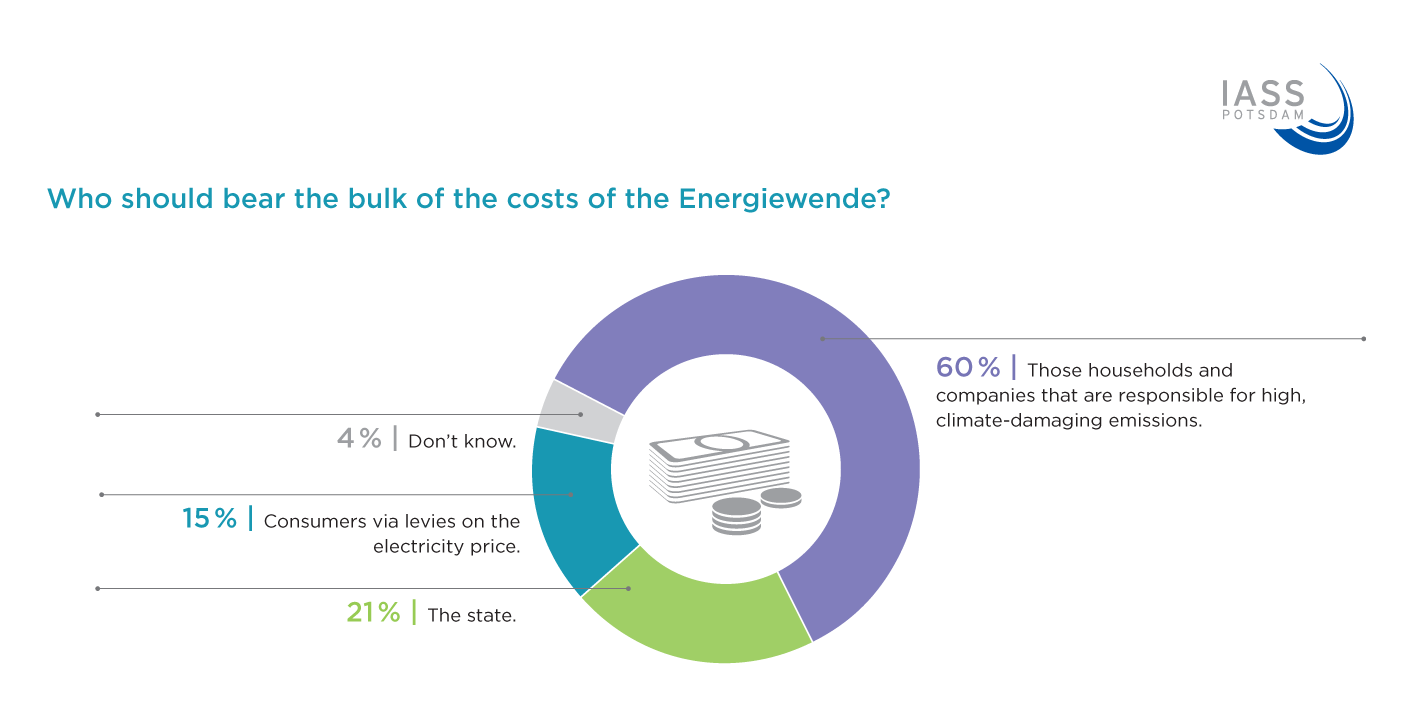

Three quarters of Germans say that the Energiewende is a joint task that they are called on to participate in! The Wall Street Journal recently wrote – in a piece signed by the entire editorial staff, no less – that the Germans voted against the Energiewende in the September elections. Clearly, this is not the case. Rather, the Germans accept the cost but want the burden spread across more shoulders fairly. At present, energy-intensive industry is largely exempt from certain grid fees and the renewable energy surcharge. Yet, these companies emit the most carbon.

This finding suggests that the public would support a carbon floor price even if industrial firms faced higher costs as a result. At the household level, it also suggests that the public would like to have tiered rates by consumption level; those who consume little would pay less per unit, while those who consume more who start to pay more per unit as well. Thus, everyone, including the poor, would get an affordable minimum amount of electricity if politicians react to these findings.

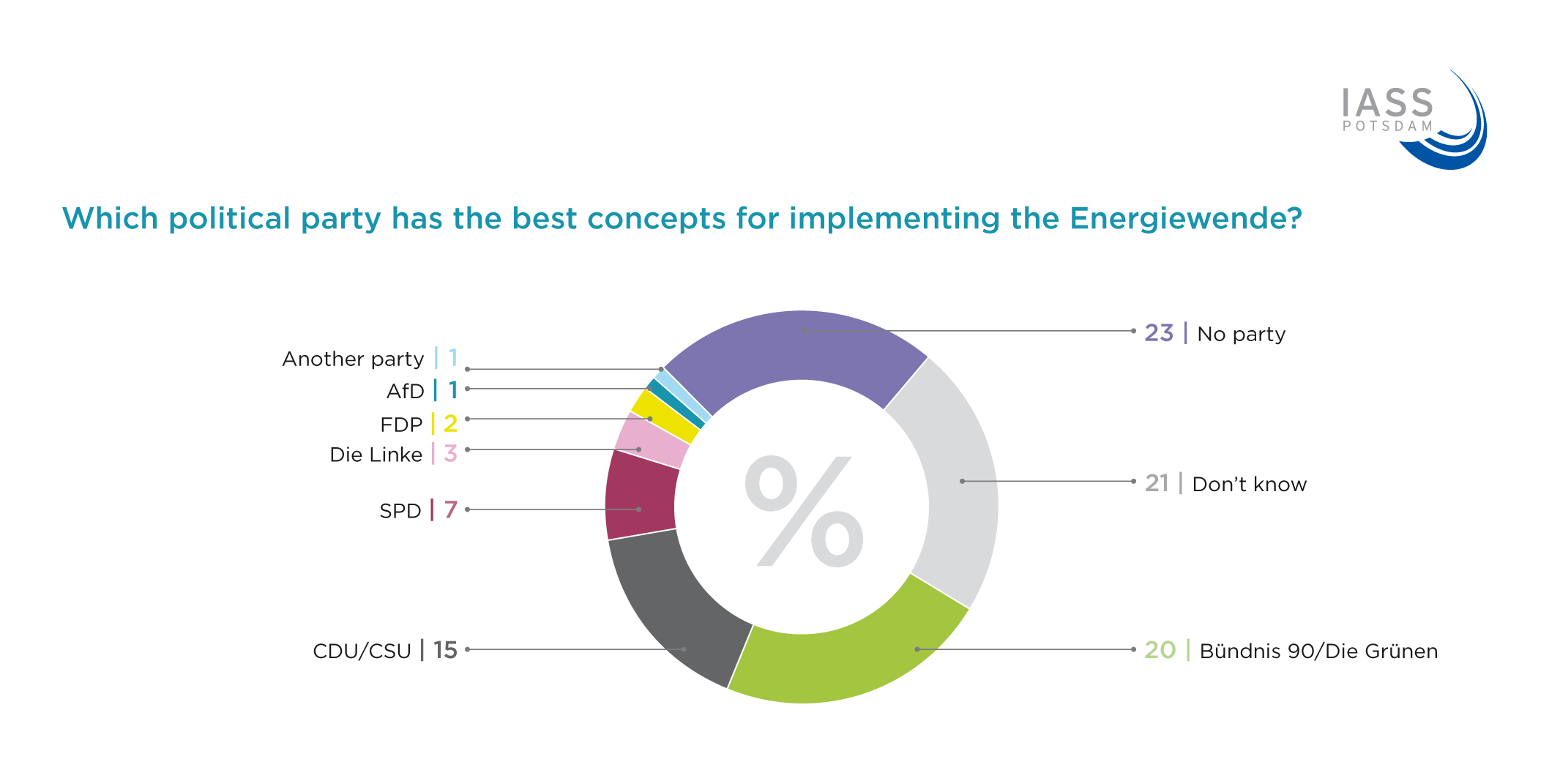

Speaking of politics, the Germans surveyed stated that the Greens were the party with the best concept for the Energiewende’s implementation, followed by the Christian Union. All other parties were far behind. But the largest group said that “no party” has the best concept – further evidence that the Germans like the idea of the Energiewende more than the way it is being implemented. Indeed, twice as many people liked the Greens’ concept than voted Green in the September elections, in which the Energiewende was not a big topic.

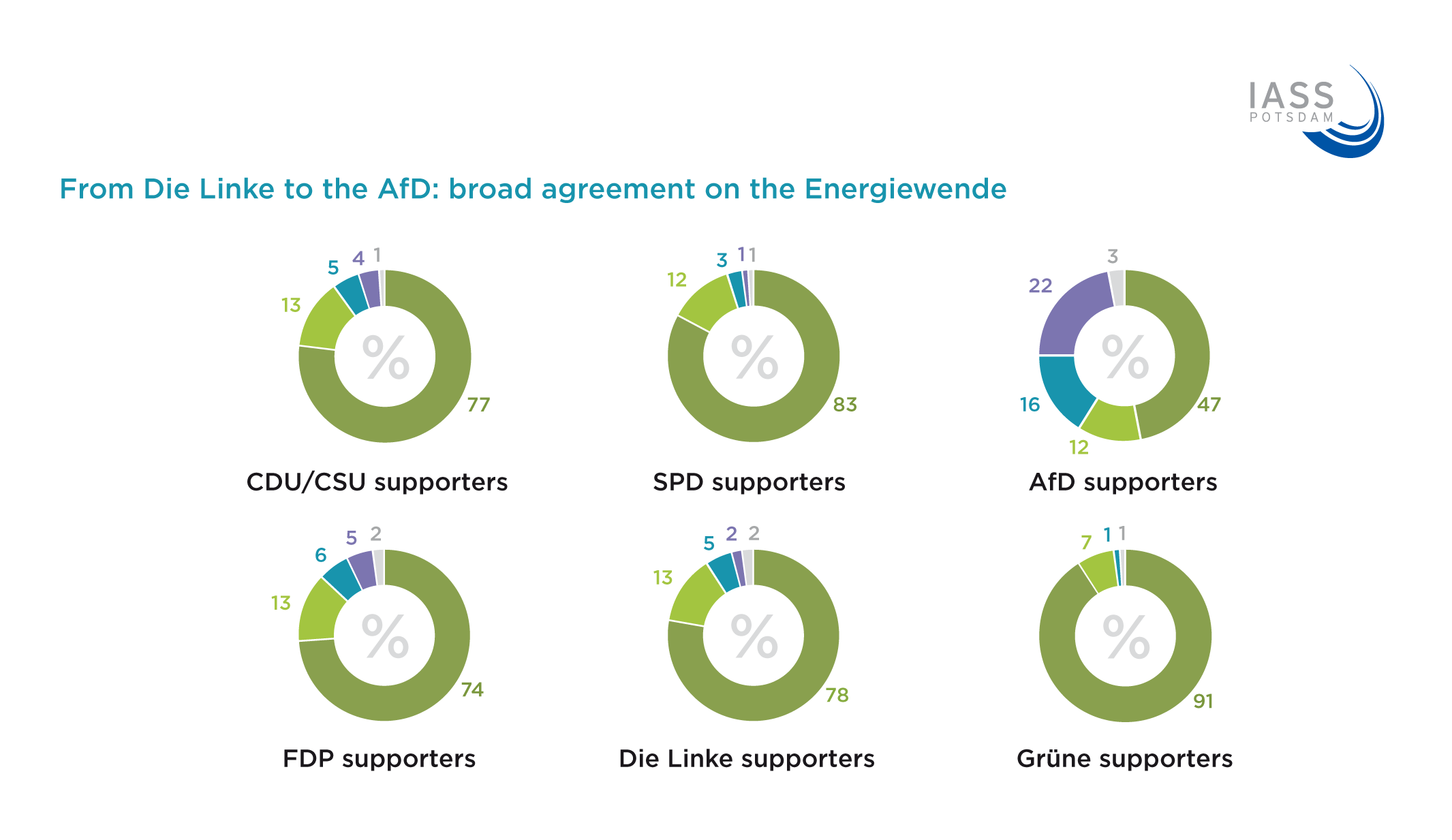

When adjusted by party support/membership, the survey revealed a majority of Energiewende fans, with almost no difference between the main parties – including libertarian FDP voters, whose party did not run on a particularly anti-Energiewende platform but turned out to be big opponents of a coal phaseout during the failed “Jamaica” coalition talks. Even most voters of the AfD, a party that denies climate change and would stop the Energiewende immediately, think the energy transition is a good idea, though support here is the lowest.

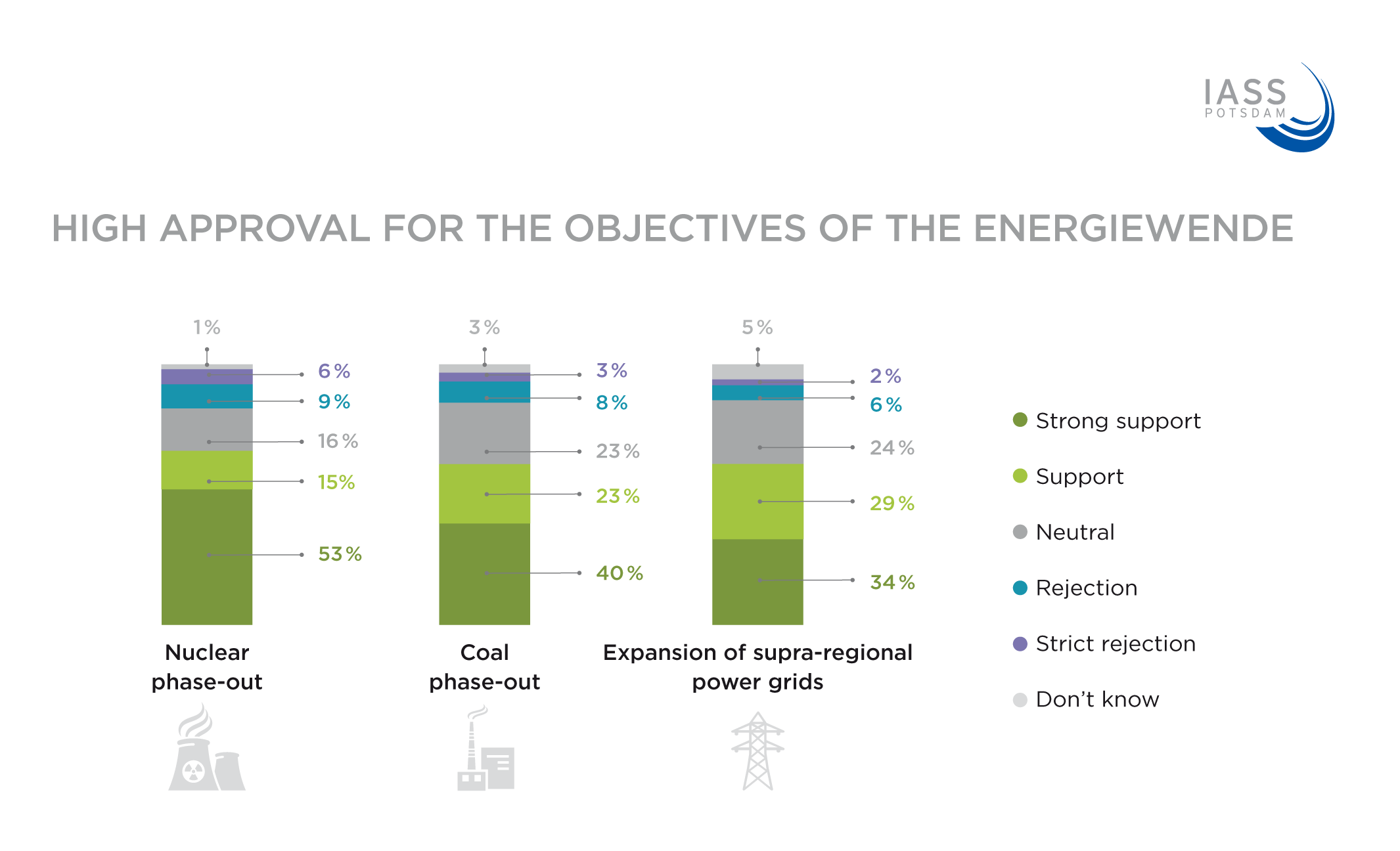

At 63%, the Germans are roughly as supportive of a coal phaseout (which is currently being debated politically) as they are of the nuclear phaseout (68%), which will be completed in 2022. “We were a bit surprised by this outcome, which shows that the public is more ready to phase out coal than politicians may realize,” Setton says.

In my opinion, the Social Sustainability Barometer has two main messages: 1) it tells German politicians that they can be more ambitious in spreading out the cost burden and phasing out coal, and 2) for the outside world, it is further evidence that the Energiewende is not a top priority for most voters during elections. If the Germans thought about the climate and environment more, they would obviously vote Green more often. And those who vote for other parties like the CDU would also force their parties to support the transition. As it is, education, jobs, migration, and other issues remain in the foreground.

The Barometer is to be repeated next year, so a trend could be revealed. It is the product of the Dynamis project, which brings together the IASS, the Innogy Foundation (with ties to coal utility RWE), and the 100 Percent Renewable Foundation. The partners thus cover the entire spectrum of energy standpoints. The questions posed to participants were thus not leading in any particular political direction.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

The link to the wsj-article isn’t working, try this one for laugh:

https://www.wsj.com/articles/germanys-green-energy-revoltgermanys-green-energy-revolt-1510848988

This survey neglects to penetrate into many contradictions encapsulated within Energiewende advocacy. For instance, only about 2% of the building infrastructure is refurbished annually for reducing CO2 emissions in line with Germany’s climate protection commitments. The state of Schleswig-Holstein possesses one of the highest levels of wind power generation per inhabitant anywhere in the world, but only 29% of the railway network is electrified – the lowest ranking among all German states. The Barometer survey booklet also notes on page 8 that sustainable development opportunities must be sought by all participants in regions dominated by the lignite industry. However, the necessary transformation process could take decades at present funding levels.

[…] society. For instance, in a recent report from IASS Potsdam, German society largely supports this transition, and view it as a worthy, beneficial, long-term goal for the country, the […]