Stopping the growth of the coal sector makes more than just environmental sense. If a stable climate translates to fewer and less severe disasters, the financial argument for insurers is just as compelling. Dan Gocher argues that coal projects should be excluded from investments due to their contribution to climate change.

Insurers are backing away from coal, divesting billions of dollars (Photo by Rikuti, edited, CC BY-SA 4.0)

European insurers are increasingly taking action to limit their exposure to the coal sector, while American and Australian insurers continue to support business as usual.

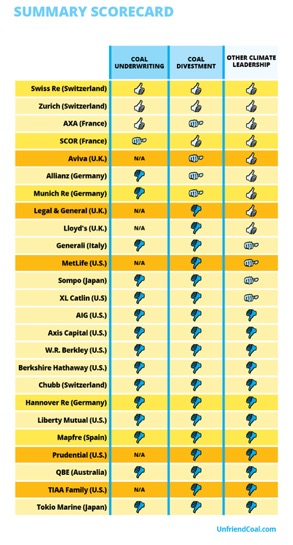

A newly published assessment of 25 of the world’s largest insurers and reinsurers (see table below) found that 15 companies have sought to reduce their investment exposure to the coal sector, by divesting approximately US$20 billion worth of bonds and equities.

Swiss insurer Zurich recently announced it will divest from and cease underwriting companies which depend on coal for more than 50 per cent of its business. Swiss Re and Lloyd’s have announced that forthcoming policies will apply similar restrictions.

The definition of what constitutes a coal company, however, is up for debate. Zurich’s threshold of 50 per cent will exclude Whitehaven Coal, but not BHP Billiton, despite the latter producing far more coal by tonnage.

The distinction is important, as any type of restriction gives the impression that insurers are taking action, while allowing the largest and often most egregious companies to continue opening new mines and constructing new coal-fired power stations.

Some of the world’s most aggressive coal developers – including Korea’s KEPCO, Japan’s J-Power and Malaysia’s Tenaga – would not be excluded under a 50 per cent threshold.

Most insurers claim to take a project-by-project approach, allowing them the flexibility to exclude countries, subsidiaries, or individual projects based on Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) criteria. Yet none of this information is public.

Several insurers have indicated that they would not underwrite new coal mines, or would exclude companies with a poor environmental record. This raises the question about whether Adani would make the cut, given its poor track record in India and elsewhere.

Yet no insurer has taken the view that projects should be excluded from underwriting due to their contribution to climate change.

This has broad implications, not just for the insurance industry facing increasingly severe weather events, but also many homeowners and businesses that are quickly becoming uninsurable.

Last October, Australia’s QBE declared “2017 will likely prove to be the costliest year in the history of the global insurance industry”. One of the worst Atlantic hurricane seasons on record, coupled with Tropical Cyclone Debbie in NSW and Queensland, saw QBE book a pre-tax hit to earnings of US$600 million.

The world’s largest reinsurer, Munich Re, reckons that at some point in the future, catastrophe insurance will become unaffordable. And if you think that sounds like a death spiral, you’re not alone.

Tom Herbstein from ClimateWise at the University of Cambridge declared that “climate change fundamentally challenges the existing insurance business model because it is rendering actuary analysis in many places obsolete”.

The experience of Australian insurers in recent years confirms this to be the case. Both IAG and Suncorp have incurred claims from natural disasters greater than provisioned, for eight and nine of the last ten years, respectively. Of the major Australian insurers, QBE and Suncorp continue to underwrite parts of the coal supply chain.

In addition to the risks of providing insurance in a time of increasingly severe weather, the global insurance industry is responsible for managing in excess of US$31 trillion in assets.

The Financial Stability Board’s Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures made clear the risks posed to investors from prolonged investment in the fossil fuel sector. Yet only US$4 trillion of those funds under management have made any form of divestment from the coal sector.

Most of the progress has been shown by European insurers – including AXA, Allianz and Zurich – while American and Australian insurers like QBE, sadly lag behind community expectations. QBE continues to underwrite not just coal mines, but tar sands and offshore oil, including exploration.

Insurance companies have warned us about the risks of climate change for more than 40 years, and many European insurers regularly portray themselves as climate leaders. So why then, does the industry continue to underwrite the expansion of an industry so clearly inconsistent with the ambition of limiting global warming to 2 degrees, let alone 1.5 degrees?

As various insurers have suggested individually, the time has come for collective industry action. If the entire industry were to blanket ban new or expanded coal mines and new coal-fired power stations, we may finally see emissions trending downwards for good.

Stopping the growth of the coal sector makes more than just environmental sense. If a stable climate translates to fewer and less severe disasters, the financial argument for insurers is just as compelling.

This post has been republished from RenewEconomy.

Dan Gocher is a senior campaigner for Market Forces. He spent 15 years in the asset management industry before making the leap into climate change campaigning in 2015, and is now primarily focused on encouraging the transition away from fossil fuels in the Australian pension and insurance industries.

Market Forces is a member of the ‘Unfriend Coal’ coalition.

Crime can’t be insured, it is as simple as that.

The Dutch are banning coal power, making it illegal:

https://www.fluxenergie.nl/wiebes-wil-centrales-sluiten-door-verbod-op-energie-uit-kolen/

The official statement of the minister of Economics:

https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2017/12/13/kamerbrief-over-uitwerking-afspraak-betreft-kolencentrales-uit-regeerakkoord