Just as COP23 was getting underway, French minister Nicolas Hulot said France was not abandoning its goal of switching partly from nuclear to renewables, just postponing it. Craig Morris says more time won’t help: nuclear may keep the lights on for now, but the French remain in the dark about nuclear’s conflict with wind & solar.

Reactors can’t adapt to the fluctuations of wind and solar – France will have to choose one or the other (Photo by Jeanne Menjoulet, edited, CC BY 2.0)

France has announced (report in French) the abandonment of plans first adopted in 2012 to reduce the share of nuclear from 75% to 50% by 2025. The reason given is that such a fast reduction would not be possible without more fossil energy in the interim.

In 2011, French candidate for the presidency Francois Hollande first proposed the semi-phaseout during the election campaign. The French then elected him to implement it. And then nothing really happened – no nuclear plants have been closed, and renewables hardly grew.

To make the math easy, let’s assume that France consumes some 500 TWh of electricity each year. Nuclear would then drop from 375 TWh to 250 TWh, so we would need to add 125 TWh from renewables to cover that decrease. In 2012, Hollande still had twelve years to do so. Renewables would thus have needed to grow at around 10 TWh a year. Instead, from 2013-2016 France added a mere 3.26 TWh annually on average from solar (1.2 TWh), wind (1.6 TWh), and biomass (0.47 TWh) (data source in French – years are out of order!).

It is possible to add wind and solar much faster. Renewable power grew in Germany from 2010 (the year before Merkel’s nuclear phaseout) to 2016 by nearly 84 TWh, or 14 TWh annually in those six years. Take out the 16 TWh of biomass, and you have the 10 TWh of solar and wind alone France would have needed. France also has far better conditions for both than Germany does, not to mention more sparsely populated land.

So just in terms of the amount of energy, replacing a third of nuclear with wind and solar would theoretically have been possible starting in 2012. But now, France only has seven years left, so the task would be daunting indeed.

But there’s a bigger problem: ramping

In 2016, France had 1.6% solar and 3.9% wind power. Increasing that to cover an additional 25% at a ratio of, say, 1:2 would require another 8% solar and 16% wind, putting solar at around 10% of supply and wind at some 20%. And that won’t work with France’s inflexible nuclear fleet, which has never ramped by more than a third.

A recent post by climate change skeptic Euan Mearns on the infamous duck curve illustrates the problem well. Mearns estimates that a 10% solar share of annual supply would peak at some 28 MW on a sunny summer day in France, with demand at 45 GW. His analysis doesn’t investigate what a peak of 2/3 solar would mean for nuclear, but clearly the fleet would be pushed down to serving a residual load of only 17 GW.

Reducing the nuclear fleet by a third from 63 GW to 42 GW would thus still mean ramping by around half. The French fleet has never demonstrated it can ramp by more than a third. And even then, all other power sources – wind, biomass, hydro, and gas (France will close its last coal plants in 2021, see President Macron’s tweet below) – would need to be curtailed entirely. It would be an expensive mess, not to mention a technical challenge.

La France s'est engagée dans ces derniers mois pour une sortie de la production des énergies fossiles.

Nous fermerons toutes les centrales à charbon d'ici 2021. #COP23— Emmanuel Macron (@EmmanuelMacron) November 15, 2017

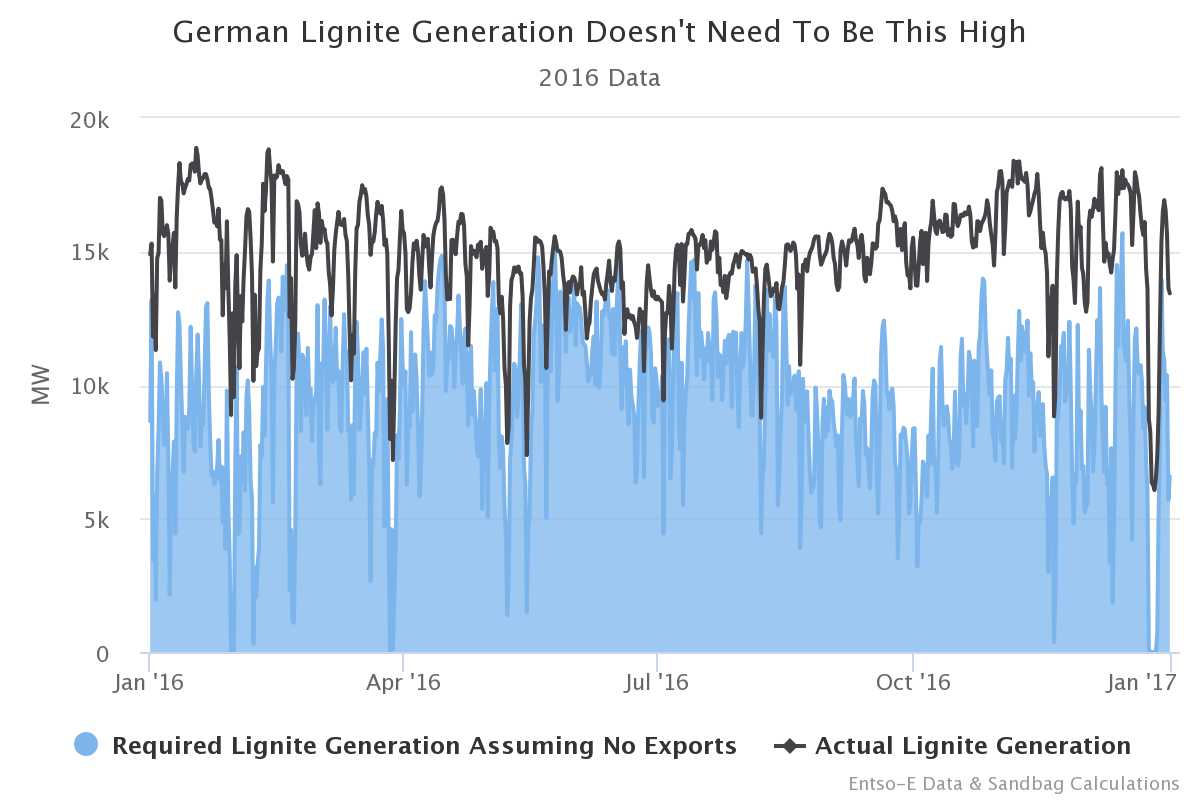

Granted, power exports could provide some relief by increasing the residual load. Exports are already rescuing Germany’s nuclear and coal fleet, though the country still has many hours of negative power prices on the spot market. UK-based climate change NGO Sandbag recently published another chart nicely showing how power exports make space for German lignite plants. (The blue area looks a bit like what nuclear would eventually have to ramp like in France.)

Source: Sandbag

Like Mearns, Sandbag doesn’t focus on what that different residual load (blue) would mean for the plants. German lignite ramps better than nuclear does, but it still cannot ramp like that blue area. In practice, lignite would thus not exactly be pushed down into the blue area shown by Sandbag. Rather, lignite plants would have to switch off for days, such as over weekends, while they wait for more extended higher levels of demand. Lignite would thus decrease much more than Sandbag expects, and gas turbines would fill the gap – which is what the French now believe is needed for their nuclear-to-renewables switch in the interim as well.

In contrast to German lignite plants, nuclear reactors really, really don’t like to switch off for a few days, come back on for a few, etc. But few talk about nuclear inflexibility in France; mainly, carbon is discussed. When France announced the postponement of the semi-phaseout, the country’s grid operator published a set of five scenarios (press release in French), one of which was for Hollande’s plan from 2012. Without ever mentioning ramping, RTE found that gas turbines would partly replace nuclear, thereby increasing carbon emissions.

The French have put so many eggs in the nuclear basket that they are stuck. Spiky wind and solar will break those eggs. A report in Platt’s Nucleonics Week from June 2016 (paywall) speaks of reactor operator EDF’s efforts to make “two-thirds (sic) of its French reactor fleet able to load-follow in 2016.” But that also seems to be the maximum, according to the report. In other words, the French fleet is already as flexible as it can be – and that’s not enough for even 10% wind and 20% solar.

So why did Hollande think a nuclear reduction was possible without fossil fuel?

The short answer is: he had no idea. People often assume that policies are based on some scientific finding or expert knowledge. But in reality, policymakers often adopt policies that sound good, and scientists then scramble to investigate what that might look like.

RTE has been producing scenarios of Hollande’s aim since 2012; it’s hidden a bit in this French PDF from 2012 as the “nouveau mix” scenario for 2030, but with 40 GW of nuclear in 2025. Still, wind would only make up 12% of demand; solar, just 4%. Implicitly suggesting that replacing a third of nuclear just with wind and solar is not even feasible, RTE never investigated that option. Rather, electricity from gas would quadruple. Ramping is not mentioned, but a main finding is that carbon emissions would go up.

I have not found any expert who ever thought France could replace a third of its nuclear power (25% of total supply) with renewables by 2025. French environmental minister Hulot stated himself on announcing the postponement that “lots of people knew it wasn’t reachable” (in French). Hollande had no French study to base his target on in 2011; it had never been investigated. And like so many people, Hollande probably thought the French nuclear fleet is far, far more flexible than it actually is.

Quelle ironie: It wasn’t Merkel’s phaseout of 2011 that was a “panicked reaction to Fukushima,” but Hollande’s. Merkel reverted to Germany’s 2002 phaseout; the country had ten years of experience already, and renewables were growing far faster than anyone had ever imagined possible. She had previously extended reactor lifespans in 2010, so her 2011 decision mainly reversed that extension. She had lots of facts to base her judgement on in 2011. And a national debate about the Systemkonflikt between nuclear and wind & solar had raged for years by then (here’s the nuclear sector reacting to it in a PDF from 2010). The Germans have long known that nuclear has to go for wind and solar to grow.

In contrast, Hollande had nothing in 2011: no scenarios, no French experience with high levels of wind and solar, and no national public discussion about the energy sector. Today, the French discussion remains poorly informed.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

Can you explain why they should transit to renewables? They already have one of the “cleanest” and cheapest energy in Europe. Germans pay far more and getting carbon intensitiy that of Ukraine.

Take a look https://www.electricitymap.org and compare “progressive” states with a lot of renewable by carbon intensity and electrical bill.

I think the future is nuclear (conventional, SMR) + cogeneration and district heating.

In posts like this, promoting renewables we are mostly talking abut electricity production. So lets say we produce unit of electrical energy which is energy in most “pure” form, it can do useful work and be converted to the lowest form – heat. A lot of this energy is directly converted to heat without doing useful work (like powering motor, electrical machines etc.) – we need it for heating homes, heating water (heating accounts for 60% of residential energy consumption).

So with renewables (wind+solar) you get unit of electrical energy, generated heat is neglectable and is disposed into environment – this heat cannot be harvested and is lost.

With nuclear (or coal, biomass, geothermal) for every unit of electrical energy you get 2 units of “useful” heat which can be distributed over district heating systems. Or else you must dispose this heat into environment (thats why those big cooling towers).

To recap, with (in this case nuclear) you get 1 unit of electrical energy and 2 units of useful heat, so you dont have to convert that 1 unit of electricity to heat and can be used to do work. Unlike renewables, every unit of electricity produced, of which 60% is converted to heat (boilers, heat pumps etc) for heating and there is like 40% left to do useful work.

There isnt just electrical energy production.

Iceland has “snowmelt” systems – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Snowmelt_system (true, they have a lot of warm water), excess heat can save lives and save money :).

As of now there is about 1% of produced “useful” heat in nucelar power plants used for district heating, industrial heat and desalination – plenty of room for improvement. And with less electrical heaters – more energy for work – less needed generation capacity – remember 1 = 3 😉 .

French nuclear energy is only cheap because the state is assuming massive decommissioning costs and constantly shoving money into EDF / Areva through share purchases and other sweetheart deals. Both companies would be dead and buried without this endless state largesse. France is now smart enough to realise it cannot go on like this, but meanwhile it is stuck with what it has, which is a massive power generation infrastructure that is unable to adjust its supply to demand, which needs massive sums spent on it to extend reactor lifetimes, and with €100 of billions of unfunded decomm costs ahead. It can see that the future is renewable, if only because this is by far the lowest cost option and will be even more so every month that passes, but it’s difficult to plan a way from here to there, as the author explains.

The real answer for France must be to strongly increase its renewables build, while also investing in storage technologies such as power2gas – to soak up zero-cost surplus power, produce H2 / CH4 / NH3, and burn it (gas turbines / fuel cells) when power is short. Also of course to feed it into existing gas / ammonia markets displacing fossil fuels and creating energy independence.

Of course France can go on like this: the Franc is a fiat currency, issued by the French government and its wholly-owned central bank, which can issue as much of it as the government chooses, to buy whatever is in the public interest that is available for sale for Francs inside or outside French borders, paying French businesses and workers to do what France does best.

Oh, whoops. The Euro is a fiat currency issued by many governments and yet by none, and there are all sorts of rules and regulations which France has signed up to follow. France cannot go on like this within the Eurozone as presently constituted.

So that’s it?

No vision, no concept, no idea how to get out of that quagmire?

If the french don’t model this, no one will be doing it for them.

Do they have to wait for batteries and then jump in really big?

The atom power plant in Fessenheim is supposed to be replaced with a big battery factory.

If the EPR in Flamanville is working …. 😉

Well the French NGO Negawatt http://www.negawatt.org/scenario/vecteurs has modeled the scenarios. ADEME (French government energy agency) have also modeled high renewable scenarios http://mixenr.ademe.fr/en . All possible but the politics / lobbies are difficult.

Well, France has already reduced the atom power, about between 1/3 and 1/2 isn’t working anymore. And not only the atom’s power but power production as such.

The UK is now exporting coal power:

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/nov/18/french-reactor-repairs-generate-profits-old-uk-coal-power-plants

and Germany as well as we know.

In Germany coal power plants are now for free:

http://www.udo-leuschner.de/energie-chronik/171001.htm

and not only the latest gas power plants as we heard some years ago. French Engie (former GdF/Suez) has ceased repairs of their Dutch and Belgian gas power plants, spare parts aren’t ordered anymore(in Dutch):

https://fd.nl/ondernemen/1226485/engie-kan-groot-onderhoud-van-gascentrales-niet-meer-betalen

Siemens is not only in trouble with the wind power section but with the (gas) turbines as well and of course with the atom power plant turbines (in German):

http://www.manager-magazin.de/unternehmen/energie/siemens-stellenabbau-in-goerlitz-auch-wegen-energiewende-a-1179439.html

The “solar shock” N.-V. Sorge calls it.

No one wants to pay for centralised power plants anymore.

From climate perspective, France should keep its nuclear fleet. French power generation emissions are 1/5 of Germany’s. As Craig observed, nuclear reduction without fossil fuels is impossible.

France is stuck with nuclear, Germany with fossil fuels. Germany is the biggest coal user in Europe. Which one is better for the planet?

What the technical limitations of the nuclear ramp rate are, is not really the main issue methinks. PV and wind can be ramped, that is curtailed, easily. The real issue is the cost structure, essentially 100% fixed costs and 0% variable costs. That makes it very unattractive to curtail/ramp, both for nuclear and PV/wind.

The assumption that solar and wind will enjoy despatch priority over nuclear during the slow French nuclear rundown is unsound. It will be cheaper, not to mention safer, to curtail the wind and solar farms than to force old nuclear reactors to ramp. France is getting into solar and wind later than Germany, and at much lower LCOE costs (not to mention rather better natural resources), so the extra cost of curtailment will be quite manageable.

What I don’t see is a real French effort on despatchables, unless they are prepared to burn a lot of fossil gas. Seasonal heat storage? Pumped hydro? P2G? Biogas? They are going to need an awful lot of it.

If costs would matter there wouldn’t be any atom bomb and no atom power. No colonies and no arms industry.

The Mafia asks for profits and these are made by exploiting the self created system.

ADEME GRDF the gas network operator recently published a renewable gas by 2050 strategy.

http://www.ademe.fr/mix-gaz-100-renouvelable-2050

Fact:

From 2015 to 2016 the atom power production was down by 7.9%,

the atom’s share in national power production is down from 76.2% to 72.3%

http://www.rte-france.com/fr/article/bilans-electriques-nationaux

http://www.rte-france.com/fr/article/bilans-electriques-nationaux

2017 is expected to be even lower and EdF issued warnings last week on their previous 2018 targets.

What Hollande and Macron ‘forecasted’ for 2025 is happening since years. But much faster.

EdF to be butchered – “Freibankfleisch” available:

http://www.powerengineeringint.com/articles/2017/11/french-government-mulls-spinning-off-edf-s-nuclear-business.html

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/edf-faces-split-to-avert-financial-disaster-b02gh0mm3

THIS is the reason why they can’t be closed now: they must be sold semi-alive.

Tangentially related: Apparently there was a major accident in a Russian nuclear waste reprocessing / vitrification plant in early October. Unsurprisingly, Rosatom denies anything happened, or at least that it was their mess. Somewhat more surprisingly, the French nuclear safety institute that picked up the fallout spike in the atmosphere also played down the whole thing. At least that’s what the independent laboratory CRIIRAD says. I don’t watch much evening news anymore, so I hadn’t heard anything about this yet. I wonder if German scientific institutes have weighed in on this, given that they’re less likely to be influenced by political interests to keep the nuclear energy industry running?

https://www.counterpunch.org/2017/11/24/a-radioactive-plume-thats-clouded-in-secrecy/

Absorbing the PV peak by pumped storage plants is easily doable. For France let’s assume 25 GW of pumping capacity with storage volumes of 4 to 5 hours. Should be no problem from the technical side.

But for wind power one would need days of storage volume. And probably, you won’t find enough locations for reservoirs of this size.

System conflicts:

Scandinavia is not willing to back-up the Finish atom power politics (centralised and failing generation, little RE support) and threatens with delivery stops:

https://energy.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/power/finland-and-nordic-neighbours-struggling-to-agree-power-supply-deal/61791387

Of course a bit more money would help to support the EPR-Jaques and Rosatom-Matruschkas, the Mafiastates as such ….. 🙂

EU money for EdF

Since there is no choice of suppliers the European parliament in Strasbourg has to purchase their lecky from EdF:

http://www.europe1.fr/economie/gaz-et-electricite-dans-certaines-villes-les-habitants-nont-pas-le-choix-du-fournisseur-denergie-3505088

machine translation:

https://translate.google.com/translate?sl=fr&tl=en&js=y&prev=_t&hl=en&ie=UTF-8&u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.europe1.fr%2Feconomie%2Fgaz-et-electricite-dans-certaines-villes-les-habitants-nont-pas-le-choix-du-fournisseur-denergie-3505088&edit-text=

Isn’t the atom power banger in Fessenheim responsible for this area?

https://www.google.ie/maps/@47.5664203,7.7762446,8z

Atom power production down again:

http://www.europe1.fr/economie/le-production-delectricite-nucleaire-et-hydraulique-recule-en-octobre-3504557

machine translation:

https://translate.google.com/translate?sl=fr&tl=en&js=y&prev=_t&hl=en&ie=UTF-8&u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.europe1.fr%2Feconomie%2Fle-production-delectricite-nucleaire-et-hydraulique-recule-en-octobre-3504557&edit-text=

Only 18 reactors are down or semi-idled today so far at 11.22 local time:

https://www.edf.fr/groupe-edf/qui-sommes-nous/activites/optimisation-et-trading/listes-des-indisponibilites-et-des-messages/liste-des-indisponibilites

Power shortage in France, Hambach burns pour la merite

French RTE (power grid manager) has issued today the first warning, only 300MW free capacity are available during peak hours:

http://clients.rte-france.com/lang/an/visiteurs/vie/tableau_de_bord.jsp

See ” Balancing mechanism’s warnings ” and ” Daily margins ”

All power import capacities from Germany/Belgium are used at full volume …. that is lignite power:

http://www.dw.com/en/hambacher-forst-activists-and-police-clash-as-logging-begins-to-facilitate-coal-mining/a-41551783

So, I’m confused. I thought it was widely acknowledged that although it is not necessary to add storage capacity in order to install intermittent renewable generation capacity sufficient, on occasion, to meet 100% of a nation’s instantaneous demand, when the residual demand is met by dispatchable fossil generation, all of which is displaced (substantially reducing emissions) by however much renewable power is available at the time. if one wants to power an entire country entirely on intermittent wind and solar generation, one would need enormous storage capacity — in the form of stored water in hydroelectric impoundments, or batteries, or compressed air, or fossil-identical fuels from power-to-gas facilities stored in underground caverns — simply to store the instantaneous excess when the sun is bright and the wind is up, for later consumption in those still, sunless periods when people huddle indoors in winter.

France, with a large component of its power system unable to ramp significantly (and more to the point, unable to save either costs or emissions by ramping, indeed incurring additional costs by doing so in the limited situations where this is even possible), is merely ahead of the curve. It needs to install storage *now* in order to accommodate additional intermittent generation without consuming more fossil fuels.

It is storage, not intermittent renewables, which will permit France at last to retire some of its “obligate baseload” nuclear generation.

[…] energy transition law, which was passed by the previous government in 2015. However, it is still lacking a concrete plan, as well as specific steps toward a new energy model – a bit like launching a boat into the […]

German Christmas ramping:

https://energy-charts.de/power.htm?source=all-sources&week=51&year=2017

Atom power was reduced from 10 GW (0.98) at 18.00 hours on the 23rd of December down to 5.5 GW at 2.00 hours on the 24th of December.

This said we know as well that the reactor Gundremmingen B is at it’s last breath planning for final closure on 31st of December.

Gas, hard coal and lignite do show a similar pattern of ramping over Christmas, the rest of the week to New Years Eve looks splendid concerning wind power input.

It could be well the case that Gundremmingen B closed down one week ahead of schedule, a Christmas gift ….?

The French atom reactors simply switched off, from 12 non-working/semi available reactors on the 23rd of December to 17 on the 24th of December:

https://www.edf.fr/groupe-edf/qui-sommes-nous/activites/optimisation-et-trading/listes-des-indisponibilites-et-des-messages/liste-des-indisponibilites

[…] transition law, which was passed by the previous government in 2015. However, it is still lacking a concrete plan, as well as specific steps toward a new energy model – a bit like launching a boat into the […]

[…] which was handed by the earlier authorities in 2015. Nonetheless, it’s nonetheless missing a concrete plan, in addition to particular steps towards a brand new vitality mannequin – a bit like launching a […]

[…] energy transition law, which was passed by the previous government in 2015. However, it is still lacking a concrete plan, as well as specific steps toward a new energy model – a bit like launching a boat into the […]

[…] This may be a little disingenuous: Germany does use coal still, but it exports some of its surplus power to France, some of that surplus being due to the success of renewables, with over 100GW of wind and PV installed so far. The planned 25% nuclear phase out in France could hopefully have worked if renewables had been accelerated faster there too, going well beyond the 45GW of so it had at the end of 2016. They weren’t, so now the nuclear phase out has been delayed, with, it might be argued, inflexible nuclear still in effect blocking progress with renewables, despite claims that nuclear can ramp up and down more: https://energytransition.org/2017/11/why-france-really-had-to-postpone-its-nuclear-reduction/ […]