The decrease doesn’t mean that less is being spent. Rather, the calculation is more complex, and two factors unrelated to the cost of green electricity play a major role. Craig Morris explains.

The surcharge has helped grow renewable energy in Germany (Public Domain)

For the second time in history, Germany’s renewable electricity surcharge (EEG-Umlage in German) has fallen slightly. On Monday, Germany’s four transmission grid operators announced the new surcharge for 2018. It will be tacked onto the price of a kilowatt-hour for most power consumers. (This German website provides all of the relevant information, unfortunately only in German.)

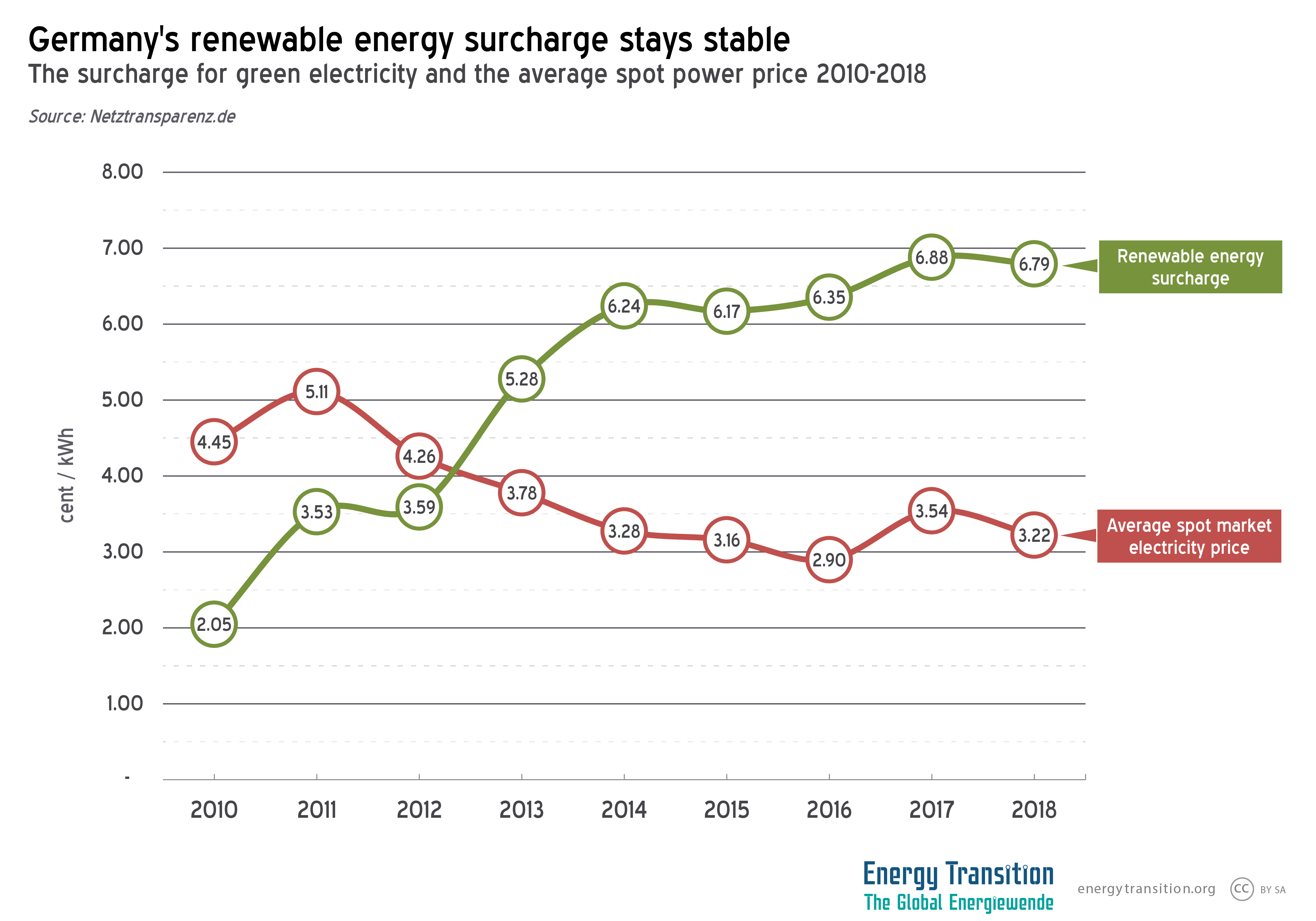

As the chart below shows, the surcharge has been reduced for next year from the current 6.88 cents per kilowatt-hour to 6.79 cents, a decrease so small that consumers will not notice it. A similar drop too small to feel occurred from 2014 to 2015.

The main increase occurred in 2010, when the price of electricity on the power exchange was added as a factor. Up to then, the surcharge represented the amount spent on green electricity. That sum was then spread across all non-exempt ratepayers as the surcharge.

But in 2010, the price of electricity on the spot market was added as a factor. Since then, the surcharge has represented the difference between payments for green electricity and revenue from the sale of that electricity at spot market prices. Those spot prices have gone down in recent years.

Another aspect is the amount of electricity consumed by large industrial firms largely exempt from this surcharge. When the surcharge is spread across a smaller number of consumers, it increases for those not exempt.

Properly understood, this share of the surcharge does not support renewables, but rather energy-intensive industry. A growing number of voices in the debate are therefore calling for the impact of these exemptions to be passed on as tax money through the federal budget, rather than as a surcharge on power consumption. If the entire amount in question were transferred from ratepayers to taxpayers, the surcharge would drop by around a quarter at once.

In 2010, Germany had roughly 17% renewable electricity, which cost around 13 billion euros. At present, both of those figures have roughly doubled. The average cost of renewable power has thus remained stable this decade, but the surcharge has more than tripled

The accompanying documents in German from the website mentioned above are more than 200 pages long and show how complicated not only the calculation, but also forecasts for the future are. Assumptions need to be made not only about the future cost of renewable power, but also about how much electricity will be consumed – and that involves an estimate of future economic growth.

More of this electricity is to come from renewables, of course, and the nuclear phaseout will also remove all remaining nuclear power by the end of 2022. By removing this excess capacity, spot market prices could rise, thereby reducing the surcharge. Likewise, there is a push to start closing more coal plants, which would have a similar effect – but that step depends on what the next governing coalition (currently being negotiated) decides.

The account for the surcharge is currently 3.3 billion euros in the black, meaning that more money has been taken in than is paid out – another reason why the surcharge dropped slightly.

The record-breaking low prices from recent auctions will not affect the calculation for several years because these projects are not built yet. Payments for onshore wind are expected to drop from 2020 (6.7 billion euros) to 2022 (5.9 billion euros) as new turbines replace old ones under 20-year feed-in tariffs. A similar effect will occur with solar around 2030. The think tank Agora Energiewende expects the surcharge to peak next year once and for all at around 7.5 cents (in German).

On the other hand, the market value of wind and solar power continues to drop. This value represents the ratio of the price paid for the electricity relative to the spot market price at the time it is sold to the exchange. A value below 1 means that the electricity is of less value than the power on the exchange. In 2016, onshore wind had a market value of 0.873, compared to 0.827 this year. Offshore wind fell from 0.921 to 0.906. Likewise, solar power fell from 0.997 to 0.949. This decrease is inevitable; it is called the cannibalization effect.

The think tank Agora Energiewende expects the surcharge to peak next year once and for all at some 7.5 cents (in German), but a decrease is in the offing starting in 2022 thanks both to the retirement of the nuclear fleet and older, more expensive wind farms. Only a change in the way that surcharge is calculated would make a big difference.

After years of indecision, it seems likely that policymakers will try to move the industry exemptions from the surcharge into the federal budget. If so, the surcharge would drop noticeably without changing the overall price tag.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

The spot market price for next year 2018 could increase due to the massive failure of the French atom power generators.

This would reduce the RE-surcharge resp. increase the amount of money held.

As of today 31 reactors in France are registered by EdF as out of business, power imports from all neighbors are on the increase.

The power “Futures” on the EEX however are stagnant.

PS

(Vera Eckert was there first )

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/international-business/temporary-french-reactor-closures-could-lead-to-big-power-price-spikes-study/articleshow/61145194.cms

In the meantime the outage list grew to 32 incl. 2 double counts for extended outages:

https://www.edf.fr/en/the-edf-group/who-we-are/activities/optimisation-and-trading/list-of-outages-and-messages/list-of-outages

The grid capacities for German-French interconnectors are booked out most of the time with very little capacities left now and then:

http://www.intraday-capacity.com/portal/php/main.php?displayBorderAtc=DE_FR&atcPart=4

Even as little as 7 MW of free transmission capacity (19:00-19:30) is worth to be mentioned.

The good part of the old EEG was the predictably declining FITs. The bad part was the opaque surcharge. Nobody can understand it, and some like the WSJ don’t even try.