Tunnel construction under train tracks in southwest Germany has damaged the only line for fast trains connecting Switzerland to Germany. Freight is also impacted. One Swiss paper says the Germans have “third-world infrastructure.” Craig Morris investigates.

German high-speed trains only have one connection to Switzerland, and it’s down (Photo by Sebastian Terfloth, edited, CC BY-SA 3.0)

You’d think that engineers digging a tunnel under the main train lines directly connecting Germany to southern Europe would be careful not to collapse the lines. And you’d think that “German engineering” could do such an easy job well. And you’d be wrong.

In mid-August, a 160-meter tunnel led to undulations in the tracks above, which have been closed until at least October 7 (Deutsche Bahn press release in German). The tunnel is now to be filled with concrete. It is unclear at this point whether a new tunnel nearby will be built later.

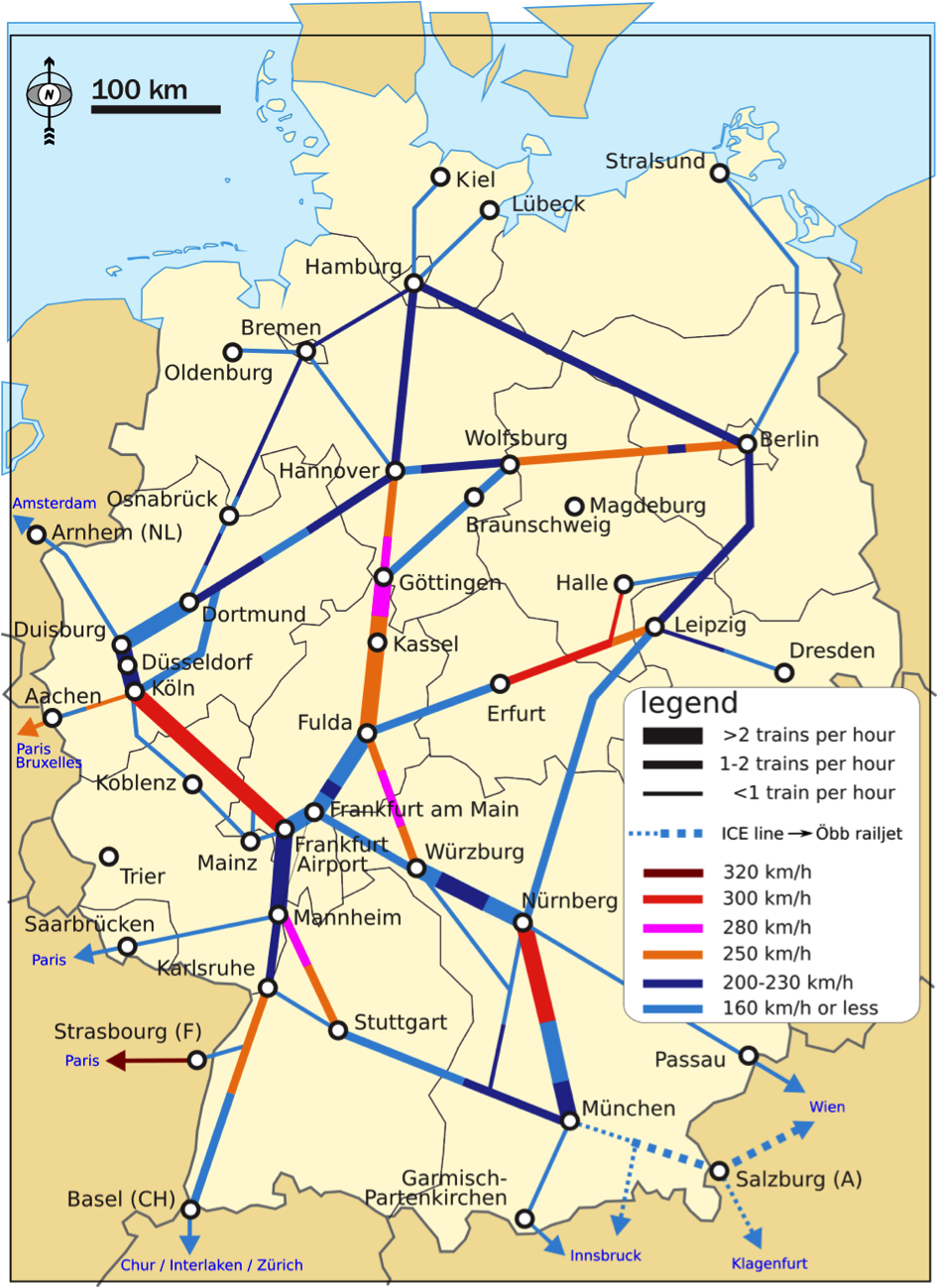

The map below shows how crucial the line is. The damage was caused near Rastatt, just south of Karlsruhe at the bottom left. As you can see, that’s the only connection for high-speed trains. Southwest Germans and the Swiss have been partly cut off from northern Europe.

The ICE trains in Germany only have one connection to Switzerland, and it’s down. Note as well that, although the trains can theoretically reach 320 km/h, they only do so in France. German tracks have never been upgraded to accommodate such speeds. Deutsche Bahn now plans to give up such ambitions altogether: the new ICE 4 trains expected in 2023 will have a top speed of 250 km/h (report in German). (Image source)

Granted, German railway operator Deutsche Bahn (a state-owned company) is providing a bus connection around the blockage, but that detour adds an hour to the trip. When I travelled on the autobahn in late August, I was expecting great traffic, but it seemed unchanged. People might simply be opting not to travel at all if they can avoid it. (I know some people who have done so.)

Freight is also being affected. The route is heavily used to transport goods. Shipping on the Rhein is an option, water levels permitting. Otherwise, all freight has to go on the road. The local newspaper Der Sonntag reports that low water levels can, however, cause much greater disruption because so many containers fit onto a single ship. The trucking sector is thus used to such fluctuations, and there are also north-south roads along the French side of the Rhine. In other words, the extent of the problem is not really new, though the cause is, and the problem is not overwhelming the roads.

Nonetheless, Deutsche Bahn faces lots of claims for damages as freight is rerouted and arrives late. BASF, the world’s largest chemicals firms (located in Ludwighafen just north of Stuttgart on the map above), is already running short of some material. And the Swiss logistics sector will also want its losses covered.

Some Swiss are not pleased. In an article entitled “Germany is a Third-World Country,” Basler Zeitung says the Swiss might want to redirect some development aid to Germany: “Germany… likes to tell Third-World countries and others… what successful climate, economic, and security policy looks like.” In this case, Germany has pledged to expand transport connection with Switzerland – and failed to do so in time. Judging from the comments below that article, lots of Germans are happy to have the Swiss bash them – and join in the bashing themselves.

This setback is yet another sign that, for whatever reason, the Germans can’t get mobility right. In addition to dieselgate, there is the “farcical saga” (The Telegraph) at Berlin’s new airport, where delays cost a million euros a day with no end in sight.

German politicians have spoken of the Energiewende as the country’s Man on the Moon project. As we point out in our history of the Energiewende, the comparison is interesting in a way not intended: Apollo 1 burned up on the launchpad, killing all the astronauts aboard. The Energiewende may still have its Apollo 1. But I always thought that disaster might be a major blackout. Increasingly, I wonder whether the Energiewende’s biggest failure might not occur in the power sector at all. Maybe it’s already happening… in mobility.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

Shit happens. Even some local transportation chaos or a massive blackout like in the US would pale in comparison to the damage and disruption we get from the country-wide “once-a-century” river floods that happen once a decade lately. (Though to be fair, I’ve never actually been in a blackout that lasted longer than a few hours, and even that not in the last 15 years…) As long as that Apollo 1 type failure doesn’t come in the form of a nuclear power plant exploding at the last minute or due to shoddily executed shut-down procedures, I’ll be happy and content.