There’s a global movement of communities and cities taking back control of their energy and water supply, and Germany’s Energiewende serves as a role model. Craig Morris takes a look at the Transnational Institute (TNI)’s report, “Reclaiming public services: how cities and citizens are turning back privatization.”

Germany dominates re-municipalization in the energy sector. Pictured here, the initiative “Neue Energie für Berlin” (Photo via Wikipedia Commons, edited, CC BY-SA 3.01)

In the 1990s, communism was dead, and privatization was in fashion. Across the world, policymakers and business leaders assured the public that companies could provide basic utility services of better quality and at a lower cost. Many of these commissions were granted for 20 years, and a lot of municipalities are now deciding not to renew contracts with private-sector service providers but instead to take things back into their own hands.

TNI’s new report (also available in French and Spanish) explicitly advises municipalities to use that planning horizon to make preparations:

It is quite strategic for cities to spend a few years to prepare the transition while waiting for private sector contracts to expire. In 20 per cent of cases (134), private contracts were terminated during the contract period, which is much harder and generally conflictual.

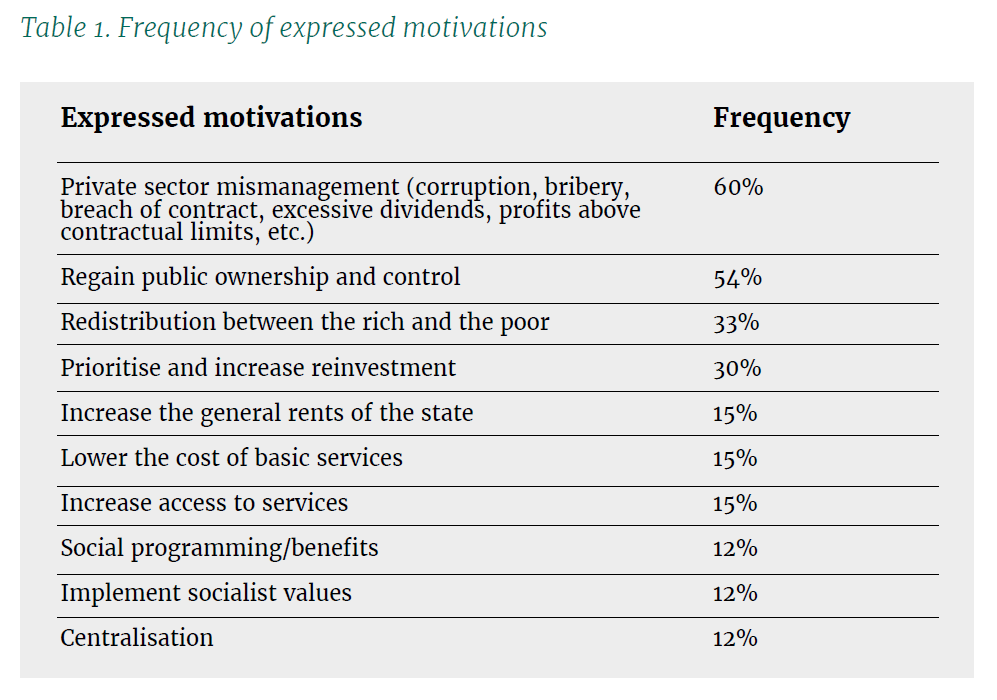

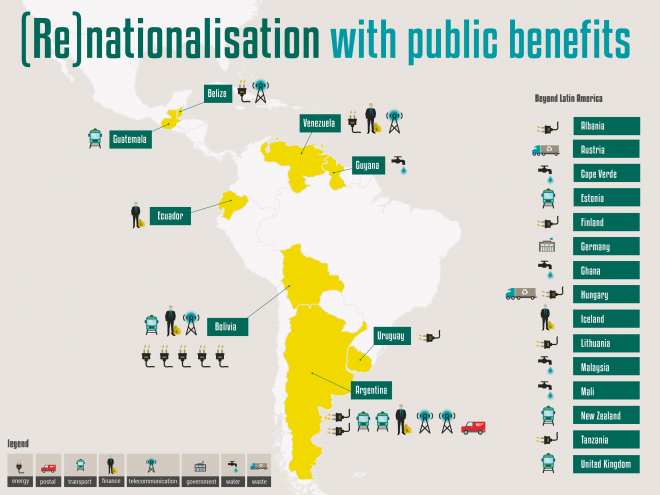

In some cases, however, quick action is taken because an immediate response is needed (for example, the re-nationalization of Japan’s nuclear reactor operator TEPCO). Other re-nationalizations took place in Latin America in sectors ranging from pension funds to postal services and air transport. What all of these events have in common with municipal ownership is a focus on public welfare and democratic control when the focus on profits in the private sector lead to undesirable outcomes. Indeed, as the list of motivations shown below shows, the main driver in Latin America was discontent with the services provided by companies:

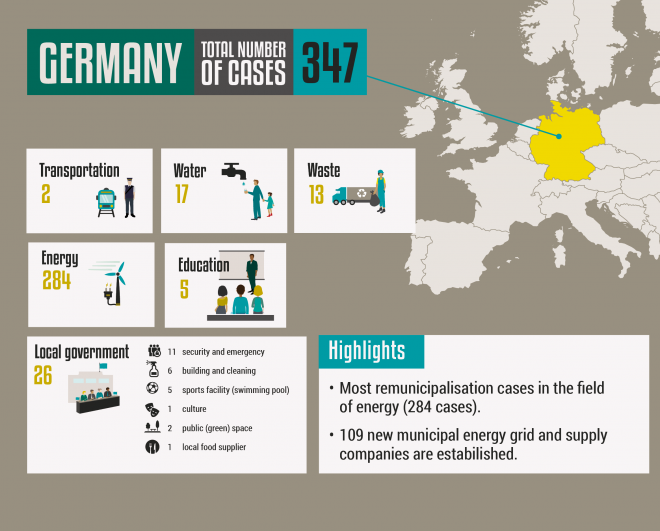

The report covers 835 examples of (re)municipalization of public services globally since 2000. An astonishing 347 of them are in Germany alone, 284 of which are related to energy.

Privatisation is failing. This is the alternative: People taking #PublicServices back into public hands https://t.co/9NUd9U9lrk pic.twitter.com/jZxrrLEjsG

— TNI (@TNInstitute) June 23, 2017

In France, the issue has largely been water supply. When the capital city of Paris decided to take back its water services, it set an example that other French cities have followed. According to Reuters, a report found that French cities “with the cheapest water rates were nearly all run by public bodies, while those with the most expensive were mainly run by” private firms.

The chart also shows, however, that Germany by far dominates re-municipalization in the energy sector. The most famous example is Hamburg, a city of some 1.5 million. In 2013, its citizens voted to take back the power grid from Danish giant Dong Energy. A similar campaign initially failed in Berlin later the same year; however, that issue has not yet been completely resolved.

Overall, the study finds that remunicipalization is far more widespread than commonly known, and it is increasingly a local response to austerity. The study argues that local ownership is often a better solution than privatization. In South America, for instance, a wide range of public services have been returned to municipal control, as the chart below shows. Argentina has seen the strongest trend towards municipal ownership, which is perhaps not surprising; after all, the country suffered a financial crisis in 2002 and was cut off from international capital markets as a result until 2016.

A study published in 2016 by German economics institute DIW came to more nuanced findings for municipal utilities in Germany. They found no significant difference in economic efficiency. Instead, there was a big difference in goals: private-sector firms focus on profits for shareholders, whereas municipal utilities try to provide better-quality services and return the profits to the municipal budget. In other words, the difference is between benefits for shareholders and benefits for stakeholders.

This reasoning is the same for campaigners in Germany. One of the people spearheading the attempt to take back Berlin’s grid recently told me that his group does not claim that they will be able to provide better services; in fact, they would basically hire the same people. What they want is for profits to be returned to citizens of Berlin rather than sent off to Sweden, where Vattenfall has its headquarters.

The Transnational Institute was founded in the 1960s in the United States to promote peace but soon moved to Amsterdam and begin focusing on global justice, especially in terms of finance. The TNI’s Board President is Susan George, a prominent critic of neoliberal globalization in the past few decades.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

In this context, the huge 1991/1992 federal law suit in which 164 East German communities prevented / undid the forcible backroom-deal sale of their local power plants and assets to the West German energy corporations should perhaps be mentioned. (Did they count those as part of the 284 (re)municipalizations in the study you’re looking at?)

For research, here two articles (in German):

20-year-anniversary write-up:

http://www.derenergieblog.de/alle-themen/energie/wie-die-energiewende-von-der-politischen-wende-profitieren-kann/

contemporary write-up:

http://www.zeit.de/1992/46/etappensieg-fuer-den-osten

I wonder if anyone has done some sort of analysis comparing how these municipally owned energy companies have fared over the last 25 years compared to similar communities where the power plants were completely privatized. (Though for it to be a fair comparison you’d have to compare East German communities with other Est German communities.)

I mean, I know it’s not all kittens and rainbows. Last time I looked, my local municipal energy company (which had at some point been at least partially privatized, though the town has bought the shares back by now) had electricity rates that were lower than what E.On offered, but still considerably higher than what I pay in my contract with a small, privately owned West German 100% renewable energy provider. And the municipal energy provider still gets its electricity mainly from a coal power plant. Which is why I don’t ‘buy local’ in the case of electricity, even though I would like to.