In Carbon Democracy, Timothy Mitchell calls into question our simplistic notions of why there is democracy in some countries and not in others. He claims that vulnerabilities in the coal sector opened up opportunities for democracy to advance, but in the past hundred years the rise of oil sector was exploited to undercut it. Craig Morris has the details.

Coal strikes forced the powerful to listen to worker demands (Public Domain)

This is part one of a series on democracy and energy; read part two next.

Published in 2011, Carbon Democracy by Egyptologist Timothy Mitchell is one of those rare nonfiction books you read all the others for – one that proposes radically new interpretations of the world and then justifies them convincingly.

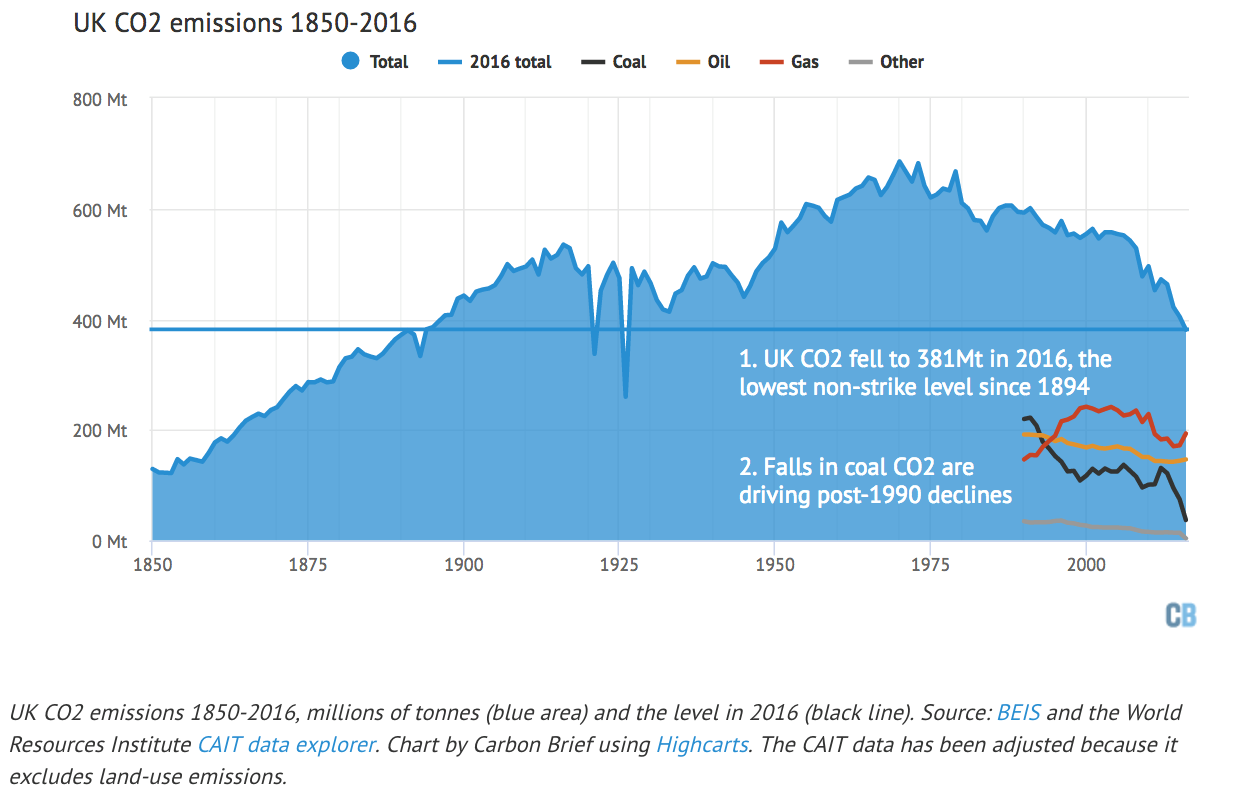

The UK has successfully reduced its carbon emissions to a level not seen since the late 1800s. But the most salient part of this chart are the two dramatic dips in the 1920s. They were the result of strikes at coal mines, which threatened to cripple the British economy. (Source: Carbon Brief)

For instance, Mitchell says the recent fashion of dividing the world into “Jihad vs McWorld” is wrong; he proposes “McJihad.” The Arab world does not “hate” our values. Rather, our consumer culture – and hence, our democracies – are based on the suppression of democracies in the Middle East, including fundamentalist Islam. Because our well-being is so dependent on fossil fuels, Mitchell speaks of “carbon democracy.”

He rejects the notion that Europe and North America naturally lean towards democracy because of some mindset: “Think of democracy not in terms of the history of an idea for the emergence of a social movement, but as the assembling of machines.”

“Democratization arises not because manufacturing allows workers to gather and share ideas… but because it can render the technical processes of producing concentrations of wealth dependent on the well-being of large numbers of people.”

Indeed, top thinkers in the West are hardly ardent supporters of democracy. Mitchell finds a lot of anti-democratic thought (or at least skepticism) in the Western world, from US political scientist Samuel Huntington’s talk about an “excess of democracy” in 1975 all the way back to the beginnings of oil exploration in territories Europe had colonized. At that time, Mitchell writes, “tolerant, educated, liberal political classes” in Europe were “opponents of democratization.”

In turn, he cites evidence that the colonized were less interested in being divided into the ethnic groups that Europeans wanted to categorize them in – such as Arabs or Turks – and “more concerned with collective well-being and economic survival.”

He finds that the coal sector was vulnerable to sabotage by workers starting in the first phase of industrialization. But in the 20th century, industrialists and politicians in the west used the rise of oil to push back popular demands. Mitchell argues that democracy requires “an effective way of forcing the powerful to listen,” and coal was better for that purpose than oil.

Take the British Navy’s switch from coal to oil around World War I under Lord Admiral Winston Churchill. Practically all accounts of Churchill’s decision focus on the benefits of using oil instead of coal (basically, more energy for the space required); see this example by US Senator John McCain, or Daniel Yergin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Prize. But Mitchell says one thing is almost always left out: labor strikes.

Around that time, the British labor movement had succeeded – largely by means of strikes – in getting the first welfare policies adopted (unemployment benefits, disability insurance, healthcare, etc.). Parliament had cut back on military expenses to cover these services, and taxes on the rich had been increased. Churchill feared that strikes might compromise the military’s ability to maneuver, specifically because the Navy needed coal of the highest quality (anthracite). And the only place in the UK where this could be found was South Wales – exactly where strikes were taking place during the Great Unrest, when Churchill took over the Navy. “The general strike ‘policy’ is a factor which must be dealt with,” Mitchell quotes Churchill in the wake of strikes in 1911-12.

When war broke out in 1914, the British government appealed to workers’ patriotism to prevent crippling strikes. But after the war, coal miners and other workers vented their pent-up resentments in strikes that truly slowed down the economy – and vindicated Churchill’s decision to move from coal to oil for the Navy, the latter being harder for workers to sabotage. In my next post, we’ll see why the coal sector was more vulnerable to worker resistance. Surprisingly, it was the oil companies themselves that sabotaged the oil supply throughout the 20th Century.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

The timing doesn’t fit. Democratic movements arose in the first half of the 19th century, when the dominant industry was textiles and labour was unorganised. Andrew Jackson’s version of democracy was agrarian (as well as genocidal against Native Americans). The “people” that élites feared were city mobs, not striking miners.

Churchill’s title in the First World War was First Lord of the Admiralty, not Lord High Admiral. There hasn’t been a real one since 1709, when the job was handed to a committee (“the Commissioners for Exercising the Office of Lord High Admiral”, normally known as the Admiralty). There have been honorific Lords High Admiral, usually the monarch.

[…] my previous post on Timothy Mitchell’s book Carbon Democracy, I presented his thesis that democracy comes […]

In defence of the thesis, I will concede that underground mining does have a different political flavour than factory work. It’s not possible for managers to exercise the same detailed, minute-by-minute control of miners, who have a lot of delegated responsibility. In Ouro Preto in Brazil, slave gold miners in the 18th century were able to assemble enough money to build an ornate baroque church. In addition, the dangers of underground mining created stronger bonds of solidarity than is normal in a factory. So once coal miners got organised in unions and learnt about socialism in the second half of the 19th century, they became a formidable political force.

[…] is part four of a series on democracy and energy; read parts one, two and […]