Recently, our American Germany-expert Craig Morris described the Dutch reactions to the upcoming end of domestic gas in the Netherlands. Today, he explains – with help from an Irish researcher based in Denmark – why the Dutch are banking on district heat.

District heat: can it solve the Dutch gas problem? (Photo by Bill Ebbesen, edited, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Dutch are running out of gas. But instead of trying to use the existing gas lines to switch to renewable gas, the Netherlands is building up an entirely new network for district heat.

Bart van den Heuvel, a Dutch citizen, doesn’t like the idea “as long as the network delivers waste heat from fossil fuels.” So he is fighting against being forced to buy this heat (report in Dutch). Generally, district heat connections are mandatory where available because consumers opting out would make the system less efficient and hence more expensive.

On the other hand, other options are not better over the long run. “The Dutch have gas lines far exceeding their potential for heat from biogas or power-to-gas,” Marijke Vos of GroenLinks (the Dutch Green Party) told me in November. “District heat just makes more sense.”

Other environmental experts agree with van den Heuvel that waste heat from fossil fuels is not an option for the long run – but also with Vos that district heat needs to be developed nonetheless. Evert Hassink of Milieudefensie (the Dutch Friends of the Earth) says his organization “does not support district heat from gas for the future.” For him, the options with district heat are manifold: “Biomass is hardly available, but waste incineration can be connected. We also hope that geothermal can play a role.” His colleague Peter Kodde adds, “we are in favour of district heat as long as it does not create fossil lock-in.” Elbert Huijzer of Dutch network company Alliander concurs: “We do not support district heating from coal or gas power plants, but for the time being it is better to use waste heat from fossil fuels than just waste it.”

Potential far exceeds need

To understand district heat better, I called David Connelly, who heads the Heat Roadmap Europe project, the EU’s most advanced one for heating & cooling. “Power-to-heat will make up a quarter of our heat supply in the long run,” he told me, “and the excess heat we already have is greater than our current demand for heat.”

Like Huijzer, most experts speak of waste heat, but Connelly prefers the term “excess heat” to avoid confusion with heat from waste incineration. “Heat is created from lots of energy conversion and industrial processes,” he explains. “So the first step is excess heat recovery, and the second is renewable heat.”

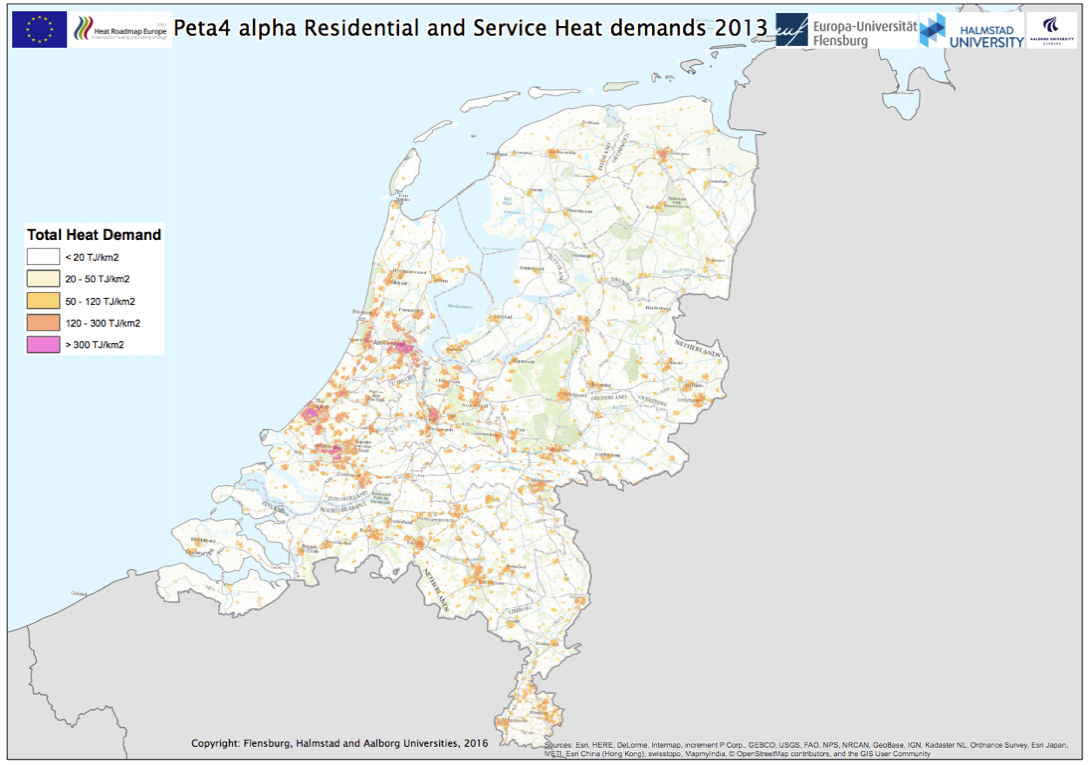

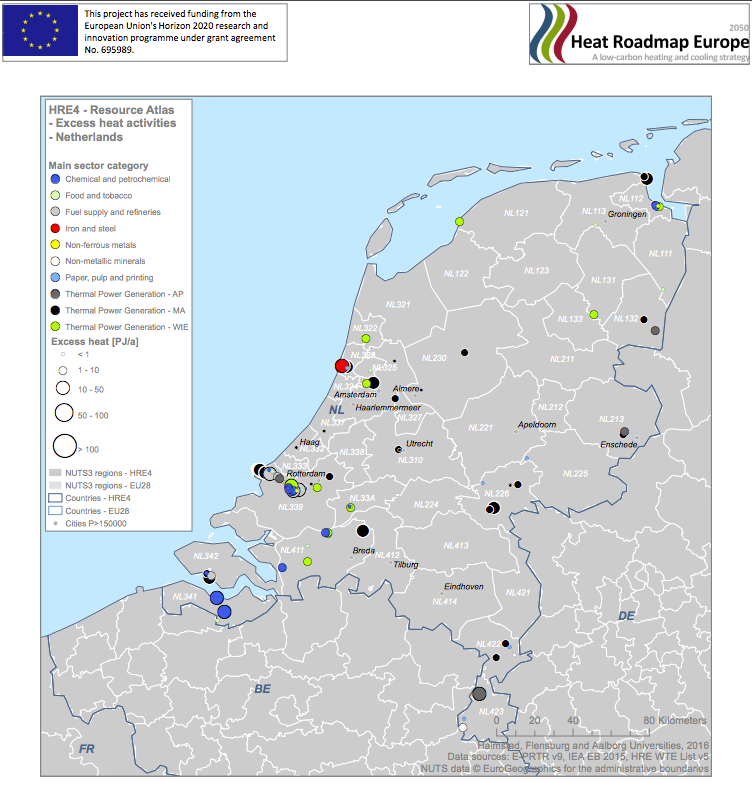

A map of heat demand (top) and excess heat supply (bottom) in the Netherlands. The spatial overlapping is salient; where heat is available, there is often demand nearby, and vice versa. The two simply need to be connected. (Source: Heat Roadmap Europe)

“Central heat supply is more efficient overall than numerous distributed units,” Connelly adds, so you start by building district heat lines and then worry about sources later. This order is acceptable, he argues, because “for supply, there are so many options.” You can, for instance, have solar thermal systems, co-generation units, and industrial heat feeding into the same network. “It’s all still just heat, so it works,” says Connelly. “But switch to a different type of gas mixture, and you have to swap out a lot of equipment.”

The gist of Connelly’s argument is that we don’t need to wait for renewable heat to build district heat networks. “The timeline begins today,” he argues. “It’s easy to change the supply chain for district heat later to move from fossil fuel to renewable heat.”

A video explaining how to use the Pan European Thermal Atlas in Connelly’s project.

Huijzer would add one point to Connelly’s argument: “the first step is to reduce the amount of heat needed,” such as by insulating buildings. And both agree that heat should not focus on biomass crops. “Bioenergy is a high-quality resource,” Connelly states. “It can be used for many purposes. But heat is a low-quality application. It doesn’t need high-quality biomass.”

Connelly is also spot-on with his assessment of why district heat networks are popular in some countries but not in others: “the reasons are not technical, but political,” he says. “Where you have fossil resources that need to be sold, you don’t have district heat.” Simply put, waste heat recovery increases efficiency and reduces consumption – so it’s bad for business if you sell energy.

Too bad the Dutch had to run out of their gas resources before they did the right thing and started building district heat networks. But then again, they are no worse than the rest of us in that respect.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

very nice video on the heat roadmap and good to hear that the Dutch are moving on this. The gas heating habit is indeed hard to break. [ ‘insulting buildings’ ? ]

Thanks, good catch, it’s been corrected!

Decision made: district heating is coming to Groningen

https://www.deingenieur.nl/artikel/groningen-krijgt-aardwarmte

http://warmtestad.nl/

Power generation could come with it.

In sunny Amsterdam the people are trying to by the coal power plant Hemweg:

https://cleantechnica.com/2017/03/24/energy-startup-vandebron-bids-dutch-coal-power-plant-turn-theme-park/