A video made by HuffPost last year praises ocean energy. Today, Craig Morris takes a look at how the technology has progressed – and what is wrong about how that video portrays renewables that work.

Waves or sun — which will be the future of renewable energy?

Last year, the Huffington Post produced a video about “ocean energy.” I have covered the topic for some 15 years. During that time, little has happened. People had high hopes for the Pelamis technology, a kind of chain-link sausage that rode atop the water, generating power as the wave bent the links back and forth. The force of the water turned out to be too much for the unit, which broke. But maybe the idea just needs tweaking; the Chinese have apparently copied the idea – and by copied, I mean possibly stole.

Other options have worked better, but they require special geographical conditions. France, for instance, has had a working tidal energy facility since the 1960s. And British playwright George Bernard Shaw famously wrote of a trip to Orkney taken in 1907: “Four times a day the tide swept past, with enough power to electrify all of Europe.”

Orkey is now home to the European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC), and various projects have gone up around the world. There is also some interesting news this year about ocean energy in the UK. But let’s first deal with some issues in the HuffPost video, which unnecessarily denigrates wind and solar.

The German renewables community rarely, if ever, plays wind and solar off each other like that video does. The real enemy, of course, is conventional energy. One reason the Germans have made so much progress is because they know who is friend and who is foe. Too many Americans still don’t.

Numerous claims in the video are counterproductive:

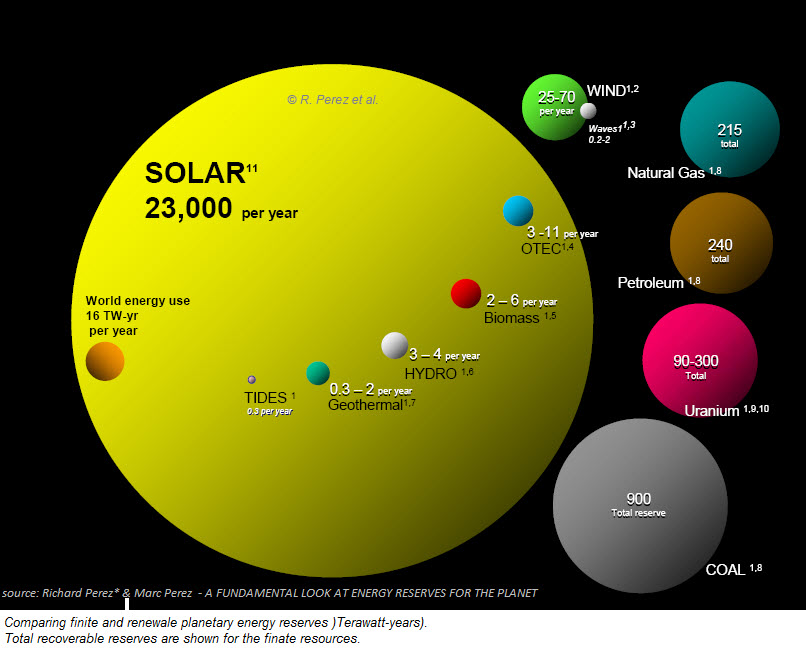

- “Wave energy is estimated to be able to supply more than the whole world’s power consumption.” Wind potential is several times greater; solar, hundreds of times greater.

- “The area of a wave farm will be much smaller than, say, a comparable solar farm of the same output.” Solar on rooftops takes up no space, and we simply do have space for ground-mounted solar in many countries.

- “Waves are pretty predictable.” Yea, but not more than wind and solar.

- “By being fully submerged, we have zero visual impact,” the video states while showing wind turbines. No one is obligated to dislike the sight of wind turbines; it’s a matter of taste. You can just as easily be proud of them.

Europe used to be cluttered with windmills. They only became an eyesore when modern wind turbines competed with conventional energy, and a smear campaign began. (Photo by Pavlemadrid, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The technology proposed is a kind of artificial basin that fills up and empties with the tides. The water passes through turbines in the barrier itself. To emphasize the positive environmental impact, the video speaks of an “artificial reef” forming around the barrier – but this often happens around pretty much anything you put in the water, including offshore wind farms.

So how is the company in the video doing?

Nine months later, Carnegie Wave Energy is now Carnegie Clean Energy and doing business in photovoltaics as well (I guess solar isn’t so bad after all). Apparently, the ocean energy sector isn’t mature enough to sustain a company on its own.

Nonetheless, there is some good news about ocean energy. Scotland has provided three million pounds in funding to numerous firms, including Carnegie, for marine projects. But the big news is the Swansea tidal power station proposed in Wales, which seems to be moving forward. But these projects are not the kind of wave projects that Carnegie proposes. The best that tech has to show for itself at the moment seems to be smallish test sites like the UK’s Wave Hub.

R&D is important, but not everyone is convinced. Two bloggers at Energy Matters have scathing criticism of the project, especially in light of the overstated claims about it (check this out from Australia, and note: Energy Matters is equally skeptical of other renewable energy sources and also argues that climate change is the least of our troubles, but if you want to find some logical thinking outside your bubble, I highly recommend that blog). In particular, the price of that ocean electricity from Swansea is likely to be more expensive than the already unaffordable new nuclear in the UK. Amazingly, the English remain lukewarm at best about their greatest power source: onshore wind.

And there, we come full circle, for the main problem the English have with onshore wind is the visual impact – a true marketing coup by the conventional energy sector. Little Britain (England and Wales) could probably make do with wind power onshore and off at a lower price in combination with solar and biowaste; Scotland already loves onshore wind. If a little ocean energy is used, fine – but it is unlikely to be the backbone of any renewable future.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

Waves come from wind, so wave energy is wind energy with a lag and some smoothing. It still varies (predictably, as Craig notes) with the weather patterns. It is not despatchable, the real disadvantage of wind and solar. Since these are already the cheapest form of power generation, it’s hard to justify large further investments of public research money in wave technology. (Private investors are free to make their own bets.) Put the long-range money into technologies that can offer real advantages here, like CSP with hot salt storage and EGS geothermal.

Both the HuffPo authors and Craig make the mistake of lumping wave with tidal. This is a mature and reliable technology; the Rance tidal plant in Brittany was opened in 1966, half a century ago. It’s not despatchable, but the daily tidal cycle is known and calculable ahead for centuries. The problem is that the total number of suitable sites is very limited. Spain for example has plenty of coastline, but a useless tidal range.