Today, Craig Morris is back with a new chart added to our e-book this year. It concerns Germany’s development bank—and it stems from coverage of solar in Germany at the Economist.

The KfW, a German government-owned development bank, is the world’s biggest green tech lender (Public Domain)

A decade ago, the Economist accused Germany of taking solar panels away from developing countries with its brand-new feed-in tariffs:

Since the German government fixed the price for solar power at munificent levels, the country has been sucking in huge numbers of solar panels that could be put to better use in sunnier climes.

If we always looked at the world this way, we would find that many things we have in developed countries “could be put to better use in sunnier climes,” but we rarely see things that way (it would require sharing). The statement was clearly uninformed anyway; at the time, German development bank KfW was already the single largest lender for clean tech, with a volume twice as big as even the World Bank. But I did not know how other comparable bank groups stacked up in comparison, and I never investigated the matter further.

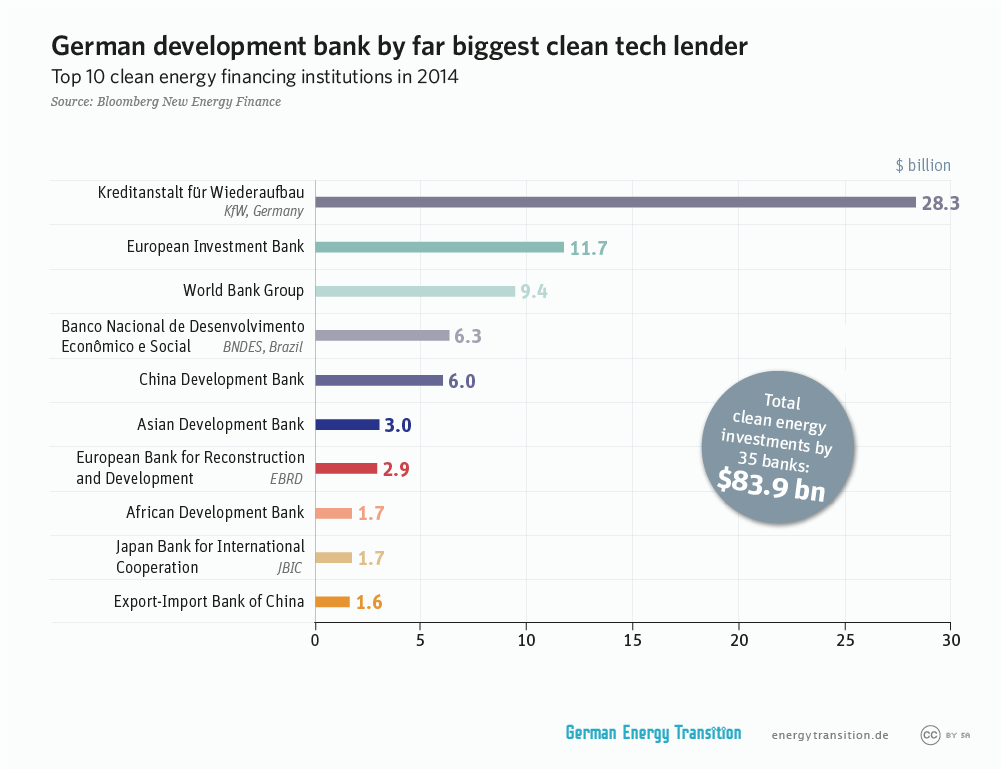

Then, in 2015, BNEF published the data I wanted a decade ago. As the chart below shows, KfW is now three times bigger than the World Bank in terms of clean tech loans and 2 ½ times bigger than the European investment bank in second place. According to that report, this list alone accounts for a third of total funding in the sector. KfW makes up a third of the total investments in the chart (83.9 billion), so this German development bank alone covers 1/9 of loans for clean energy worldwide.

To put this into context, Germany spent around 12.5 billion euros on Official Development Aid (ODA) in 2014. Clean energy makes up only a fraction of total ODA, however. So we see that the special funding Germany provides for clean tech is not only far greater than what other countries provide, but also twice its own development aid.

Cherish the irony—the Economist accused Germany of taking clean energy technology from the poor when it was actually the largest enabler. Repeatedly, that weekly draws seemingly logical conclusions without actually bothering to check its assumptions (say, whether German policy is indeed not taking renewables away from developing countries because its development bank is the biggest enabler of renewables for them). My favorite is the “insulation instead of photovoltaics” meme. Here is the Economist again from January 2014:

The largest source of renewable energy in Europe is wood. The cost of subsidies has been far greater than anyone had expected: €16 billion ($20 billion) in Germany in 2013, which works out at a massive €150-200 per tonne of carbon dioxide. (Home insulation, in contrast, saves money while reducing emissions.)

The meme has taken a beating since that publication as the cost of PV continues to plummet and oil and gas prices drop (thereby making investments in insulation less profitable). But most of all, the Economist once again merely draws a logical conclusion without bothering to check its assumptions in the real world. It turns out that the Germans (along with the Swiss and Austrians—I should probably say “the German-speaking world”) are leaders in Passive House architecture, which they invented. And incidentally, the UK is the biggest consumer of fresh timber in the power sector; Germany is a net exporter of wood pellets, which it mainly uses in more efficient processes for heat, and it focuses on waste products, not fresh timber.

Slowly, however, the Economist is coming around to renewables. They still don’t like solar in Germany—here’s what they had to say about the global success of solar (thanks partly to Germany’s commitment over the past decade):

Rather than the rooftop panels popular in Germany, countries where solar irradiance is much stronger than northern Europe are creating vast parks with tens of thousands of flexible PV panels supplying power to their national grids.

You’re welcome. But perhaps the clearest sign that the British weekly now accepts solar even in the UK—which is cloudier than Germany!—came this week in a piece calling for an end to the new nuclear project at Hinkley Point. After claiming that “the days of big, ‘baseload’ projects like Hinkley are numbered,” the weekly added:

In the past six years Britain’s government has reduced the projected cost of producing electricity from… solar power by nearly two-thirds…

With all respect to Downing Street, I’m pretty sure the British government didn’t do that alone. And while we’re at it—when are the British going to start helping clean tech be built in “sunnier climes” and not just at home?

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende.

That’s great and all, but the real question is: How much of those 28 billion for renewable energy projects actually went to developing countries? The KfW isn’t just an international development bank. It gives out plenty of loans to German citizens as well. I distinctly remember hearing you talk about the renewables-boosting power of purpose-specific low-interest loans for citizens and small businesses funded by taxes through the KfW in a podcast a while ago.

“How much of those 28 billion for renewable energy projects actually went to developing countries?”

why should German citizen asking this question, considering that main purpouse of KfW existance is to aid local projects and economy…

Of course it also supports project in clean energy which are international and have influence to the world, and to developing countries… and that is ok.

Vivi: You are missing the point. By supporting pv-projects in Germany the KfW brought down the cost of PV (learning curve). Now the whole world can profit from the low prices.

The Brazilian BNDES is out of place in the table here. It’s a purely domestic mechanism for channelling cheap taxpayer-supported capital to politically favoured sectors and projects. These loans are not all above-board, but the BNDES has been important in supporting wind and solar farms.