Jobs, fighting climate change, energy security – there are a number of good reasons to support solar power. But as Alexander Franke explains in his recent essay published by the Heinrich Boell Foundation, arguments by solar activists differ widely in Germany and the US. He argues that solar supporters should continue to focus their ideas and arguments on their target audience, even if that entails talking less about environmental issues.

Solar power gets more and more support from conservative partys and organizations. (Photo by Petr Katrochvil, modified, Public Domain)

Over the last three years, there has been a surprising amount of conservative support for rooftop solar legislation in many states in the US. TUSK, a group which is led by Barry Goldwater Jr., advocated fair net metering rules in Arizona and has now spread to other states. There is also a Green Tea Coalition, which originated in Georgia and unifies environmentalists and Tea Party supporters in their support of solar power. What has changed that allowed this new conservative interest in solar power? Apart from the fact that renewables are getting cheaper by the day, what is striking about these organizations is that they usually do not use climate change as an argument to support their position on rooftop PV, but instead focus on other arguments, such as economic choice and low electricity prices. It is a fitting example of how arguments for technology like rooftop solar can be reframed and how important this framing is in order to win over new constituents.

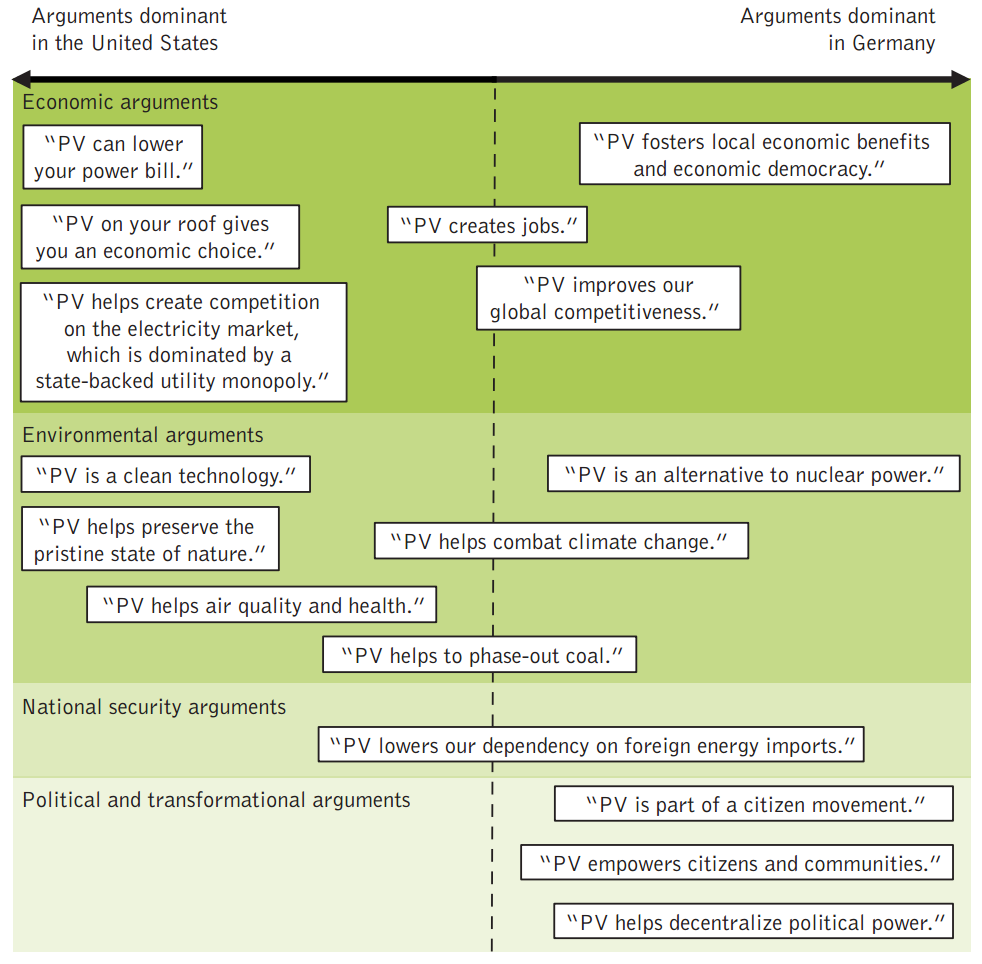

This becomes particularly clear if you compare the differences between Germany and the US in how arguments for solar are framed:

Whereas German solar activists have focused heavily on linking decentralized PV to replacing centralized nuclear power, US solar advocates have focused more on climate change and phasing out coal. Focusing on climate change most certainly was an important rallying point for supporters of renewables in the US, but, due to the political success of climate change deniers, this argument alienated key parts of the American public.

This is where TUSK and other organizations have helped to change the solar discourse by focusing on the before-mentioned economic arguments that do resonate with conservatives and Tea Party, including economic independence and cost reductions. In Germany, economic arguments have been prevalent at least since the early 2000s, when job creation and particularly global competitiveness in a future industry moved to the forefront for PV supporters.

What is more specific to Germany is the focus on community, a focus that goes back to the longstanding public debate on nuclear power (in which bottom-up solar power was seen as a benefit for rural communities). PV and renewables are seen as a tool to democratize power generation and reinvigorate rural communities by creating local jobs with local economic and social benefits. This line of argument has been particularly important in winning over conservative farmers to the benefits of renewables, similar to how Tea Party supporters have been drawing new connections between PV and the core beliefs of their peers today. Finally, while fracking has temporarily alleviated some of the US’ most serious concerns about energy security, talking about domestic energy and local jobs might be a way to bring Americans together on both sides of the aisle and has played a somewhat more important role in Germany since the recent developments on Ukraine’s eastern border towards Russia.

Overview of some of the most common arguments put forth on solar in the US and Germany.

At the core of today’s fight for solar power is not only a battle for influence and legislation, but also a struggle of ideologies. It is therefore no surprise that discussions around renewables are shaped by the preexisting cultural and political narratives. Solar advocates would be well advised to focus strategically on core beliefs of their constituents and find ways to link solar power to those beliefs. While this can mean talking about jobs and climate change with progressives, it might make sense to focus on framings of economic choice and competition with conservatives. Meanwhile, arguments of community power and local jobs have been popular with Germans and should also function well in rural parts of the US with its focus on small town values such as self-reliance and community development.

To read the full essay, please click here.

Alexander Franke (@al_f) is interested in energy transitions, particularly the political and cultural changes that are necessary for achieving a renewable energy future. Alexander holds an MA in Political Science from the Free University Berlin, where he graduated with a focus on socio-technical transitions and renewable energy support mechanisms.

On the short term it seems to make sense to use promote renewables within the conservative ideological frame. However, there are some side-effects to this approach.

First of all, conservative politicians often only care about really about corporate vested interests. The ideology is just a thin layer of cover to keep their voters happy. So you may convince conservative voters, but not the politicians. These will just invent new arguments against renewables.

More importantly, if you start to take over the conservative frame, you loose the chance to set your own frame. For example, if you start to use only non-climate change type of arguments, you help making climate change a taboo subject. In the end the conservatives determine what kind of arguments are allowed. This way you might score some short term wins, but you will loose the possibility to promote your own core progressive values, and might even loose them yourselves, because you are constantly thinking within the conservative frame.

Hey Hans,

that’s a very important point and actually one of the mistakes that were made in Germany. People talked so much about the economic advantages of renewables (through what is mostly referred to as the discourse of ecological modernisation), that it was relatively easy for opponents of renewables to debunk that frame when power prices started rising in 2012. Proponents of renewables had forgotten to talk about why we are doing the energy transition in the first place. In the end, you have to talk about environmental issues and using conservative frames can only be a temporary remedy.

A good example for the opposite, for setting your own frame and being successful, is the growing public moral outrage over fossil fuels, saying we cannot just keep going and digging up fossil fuels, it is simply wrong in our time and day. The starting success of the divestment movement is proof to me that this position is starting to gain traction.

Best,

Alexander

Alexander,

I think you mis-attribute the recent success of the divestment movement to moral outrage, when the economics of the fossil industry are beginning to be undercut by renewables with no hope of reversal.

Now that renewable electricity is becoming cheaper than coal power, the coal miners are facing some tough sledding. It was the people with the progressive values that brought renewables to this point, and now the economic argument will take over for people with more conservative perspectives, as the divestment movement will become an economic imperative. The same will come for the oil companies once the price of electric cars falls enough (which may happen surprisingly soon).

I am not discounting the importance of progressive values, but just saying that society will make broad changes more quickly for economic reasons than it would for ethical reasons (take the meat industry for example, which may itself be decimated once cheap synthetic meats are developed). It is the people with progressive values that are driving the developments that change the economics.

Regards,

Niall

@ Alexander: I have been following the discussion in Germany quit a while now, but I never heard the argument from renewable energy supporters that this would bring down consumer electricity prices. Economic arguments focused on jobs and local economic benefits.

There was a combination of factors that helped the conservative-liberal and later the conservative-socialist coalition to push the electricity price frame.

1) The original renewable energy law (EEG) reduced the feed in tariff for new systems with a fixed percentage each year, the so-called regression. Around 2008 the prices of PV system decreased much quicker than this regression. This meant that PV was oversubsidised and building a system was very lucrative, causing the EEG apportionment (an addition to the price per kWh to pay for the cost of the EEG) to rise.

2) Government freed more and more large companies from paying the EEG apportionment and the grid EEG apportionment shifting the burden to citizens and small companies.

3) Power producers got free CO2 emission certificates, but nevertheless increased their prices like if they had to buy them.

4) Renewables caused spot market prices to drop, but this was not passed on to normal consumers and only large companies profited from this.

This not happened all at the same time, but combined it drove up the consumer electricity prices up. This made it very easy for the lobby of the former utilities (now split up) to blame the whole price increase on the renewables and call for a slowing down of the energy transition. Which than carried out by the different Merkel governments.

Hey Hans,

I think your analysis is spot-on. But I think you misunderstood me if you understood me claiming that the pro-renewables camp used lower energy prices as an argument – they did not (at least in the short term view). They used a macroeconomic frame (basically the ecological modernisation discourse, arguing that renewables would create new jobs, increase competitiveness and so on). But what opponents managed in 2012-2014 was to counter the macroeconomic frame by using the rising power prices (which, as you said, had many reasons) and claiming that they threatened the industry of Germany and created energy poverty, basically arguing that the Energiewende was too expensive and that economic and enviromental interests were not reconcilable – which, as I said, was the core of the macroeconomic frame of the pro-renewable camp for two decades.

Even today that frame is used by the government and is now completely removed from any detailed debate on power prices – but has very much a macroeconomic focus on the competitiveness of German industry.

Alexander

Hi Alexander,

Good to know we agree. I was put on the wrong foot by the following sentence in your first comment:

“that it was relatively easy for opponents of renewables to debunk that frame when power prices started rising in 2012”

To debunk (entlarven in German) means to use facts and logical reasoning to show that an argument is bunk/nonsense. This is not what happened, the anti-renewable side did not directly address the arguments of the pro-renewable side. They just introduced a new, more effective (populistic) frame. The “electricity is getting expensive and renewables are to blame” frame was simple and about something that affects everybody in the here-and-now and therefore more emotionally appealing than the more long term and more abstract arguments of the pro-renewables side.

So the pro-RE frame was not debunked, but pushed aside by an emotionally more effective frame of the anti-RE side.

Dear Niall,

please excuse me for only responding to you comment now, it wasn’t visible so far. I agree that the decline of coal can be partly attributed to economics, but if you look to Germany you will see that economics or economic arguments alone don’t cut it.

Why would Vattenfall not close down their lignite operations in Germany but instead decide to sell them for a loss (!)? Utilities know that the end of coal is coming, but the usage of coal power could never only only be explained by its favourable or unfavourable economics, as it was, directly and indirectly (see the externalizations), highly subsidized throughout all times. It’s raison d’être has always been a mixture of arguments that also included energy security, local unionized jobs, well-being of the communities. This is why the changing economic outlook alone did not lead to German utilities closing down their operations (even though RWE’s coal assets are already valued negatively), instead, there have been calls for politics to financially support the operations (for example by carrying the financial burdens that come along with a later phase-out, such as pensions and renaturation of the regions).

This is where I believe the Divestment movement can make a difference. First of all, they start talking about the “real” macro-economics of coal, which are, as you are saying, increasingly looking bad. Furthermore, they shift the debate to the question of right and wrong where the answer is an unambiguous “we can’t keep doing this”.

Best,

Alexander

Hi Alexander,

From what I read on this website, I agree that in the German case it is absolutely the moral argument that is the most important for shutting down the coal power, especially since there is tradition and economic incentive to be using it in parts of Germany.

On a more global scale, it will be the economic argument that gets India and the developing countries of the world to install renewable generation instead of importing fossil fuels, which is hurting the large coal companies.

Here in Canada we are about to begin a new phase of the pipeline debate, as the conservative federal government has been replaced by a former canoe instructor who wants to approve a pipeline to appease the petroleum producing regions. The newly elected left wing Alberta provincial government (which was recently elected after a 40 year conservative dynasty) has just agreed to cap carbon emissions (much higher than the current levels) and needs to be given an export pipeline in exchange if the carbon cap is to be maintained.

I am quite convinced that the only way to seriously limit the amount of oil produced from the sands will be to transition away from petroleum fuel in cars and thus undercut the economics of production. The oil rout of the last year has done more to reduce heavy oil production growth in Canada than any argument for protecting the climate.

Reducing the use of fossil energy for transportation is the only way to limit heavy oil extraction, and improving the economics of electric cars is the best way to achieve that without requiring extensive, quick, (and unrealistic) cultural shifts in North America and probably much of Europe as well.

As much as I may wish otherwise, people in Alberta are not prepared to accept that “we can’t keep doing this” until the economics force them out of business. I think that many people will support electric mobility as it becomes practical for them and I hope that this is how pragmatic Canadians, and people in developed countries will change the economics to force our heavy oil industry out of business. If that doesn’t happen, Canadian emissions will continue to grow for a long time, regardless of how many international agreements our national governments sign.

All this to say that your thesis in the original is correct. The particular arguments in support of transition are vitally important to the target audience, and in many parts of Canada, it will be the economic ones that convince us not to invest in extracting and transporting heavy oil. The rest of the world can help us by reducing demand for liquid fuel.

Thank you for the interesting discussion.

Niall

Hi Alexander,

From what I read on this website, I agree that in the German case it is absolutely the moral argument that is the most important for shutting down the coal power, especially since there is tradition and economic incentive to be using it in parts of Germany.

On a more global scale, it will be the economic argument that gets India and the developing countries of the world to install renewable generation instead of importing fossil fuels, which is hurting the large coal companies.

Here in Canada we are about to begin a new phase of the pipeline debate, as the conservative federal government has been replaced by a prime minister who is a former canoe instructor and wants to approve a pipeline to appease the petroleum producing regions. The newly elected left wing Alberta provincial government (which is the first break in a 40 year conservative dynasty) has just agreed to cap carbon emissions (much higher than the current levels) from heavy oil extraction and has imposed regulations to shut down all the remaining coal power plants. Now they need to be given an export pipeline in exchange for those sacrifices if the carbon cap is to be maintained.

I am quite convinced that the only way to seriously limit the amount of heavy oil produced in Canada will be to transition away from petroleum fuel and thus undercut the economics of production. The oil rout of the last year has done more to reduce heavy oil production growth in Canada than any argument for protecting the climate.

Reducing the use of fossil energy for transportation is the only way to limit heavy oil extraction. Improving the economics of electric cars is the fastest way to achieve that without requiring extensive, quick (and unrealistic) cultural shifts in North America and probably much of Europe as well.

As much as I may wish otherwise, people in Alberta are not prepared to accept that “we can’t keep doing this” until the economics force them out of business. I think that many people will support electric mobility as it becomes practical for them and I hope that this is how pragmatic Canadians, and people in developed countries will change the economics to force our heavy oil industry out of business. If that doesn’t happen, Canadian emissions will continue to grow for a long time, regardless of how many international agreements our national governments sign.

All this to say that your thesis in the original article is correct. The particular arguments used in support of transition are vitally important to the target audience, and in many parts of Canada, it will be the economic ones that convince us not to invest in extracting and transporting heavy oil. The rest of the world can help us by reducing demand for liquid fuel.

Thank you for the interesting discussion.

Niall

Sorry for the double post.

See these articles for context and opinions and note the comments for a sense of the tone of the debate:

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/why-trudeau-must-approve-one-of-these-pipelines/article29784102/

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/albertas-carbon-tax-bringing-canada-closer-to-new-pipeline-notley-says/article29767086/

This article provides some insight into how the environmental groups and oil companies are now framing their debate:

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/industry-news/energy-and-resources/oil-firms-meet-with-environmentalists-in-bid-to-reduce-pipeline-opposition/article29765739/