For months, Germany has been debating how to cover the cost of the country’s nuclear waste repositories. Just when you think an agreement has been reached, more proposals are put on the table. Craig Morris explains.

German energy sector historian Joachim Radkau says German utilities, originally skeptical of nuclear, were offered limited liability in order to enter the sector in the 1960s. Now, it seems their liability for decommissioning and disposal might also be limited when they leave the sector. Photo: Craig Morris

Do German utilities that operate nuclear reactors have the money required to dismantle facilities and store nuclear waste indefinitely? That question is at the center of a current debate in Germany. To understand the issue, we need to define some terms.

First, both the German and international media sometimes talk about the “cost of the nuclear phase-out”– as though not phasing out nuclear would solve the problem. The phase-out did not cause the problem, however; the phase-in did. The longer these reactors run, the more waste they produce, so part of the cost should be lower the sooner these reactors are closed.

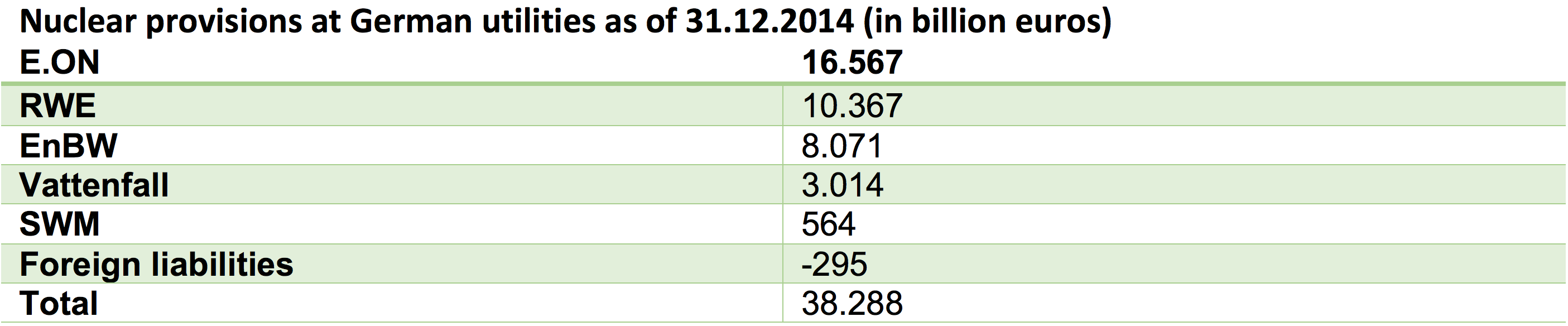

Second, the media speak of both “reserves” (Rücklagen) and “provisions” (Rückstellungen). In common parlance, those words might be interchangeable; in financial reports, they are not. Germany’s five nuclear reactor operators – E.On, RWE, EnBW, Vattenfall, and Stadtwerke München – have set aside provisions, not reserves.

The difference is partly that provisions, unlike reserves, are reported as an expense, thereby reducing profits. Lower profits mean lower tax liabilities, so German taxpayers have already covered part of the phase-out. Furthermore, these provisions are not available as liquid cash; they have been reinvested. For instance, utilities have built new coal plants that are now worthless. In other words, the money for reactor decommissioning and waste disposal might not be there.

In the past few months, an expert commission headed partly by German Green politician Jürgen Trittin has therefore been investigating the matter on behalf of the German parliament. Trittin was also a chief architect of the original nuclear phase-out of 2002. For international policy comparisons, it is noteworthy that the German government would choose someone from outside the governing coalition to head such an important commission. It is another sign of cooperation across party lines. And of course, appointing Trittin was also a clever move politically because whatever agreement is reached will not only bear the coalition’s signature, but also have a green tinge.

An example of a media report misleadingly suggesting that Germany cannot afford the nuclear phase-out. Actually, it’s the phase-in the Germans can’t afford. Source: Wall Street Journal

For the Greens, passing on any of these costs to taxpayers would be anathema, as Trittin has made clear. Nonetheless, the proposal announced in February would limit the liability of these German utilities. In return, these firms would have to hand over half of the 38 billion euros in provisions to a new public-private fund for reactor decommissioning and waste disposal. The money would have to be paid in cash – not in company shares. Coming up with that much liquidity could be a challenge for these companies. The commission also proposes a “risk surcharge,” which has not yet been specified – and the utilities are fighting against it (report in German).

The concept of shared responsibility between the state and the utilities is based on history. As utility RWE’s CEO stated back in 2014, politicians urged the energy sector to build nuclear plants decades ago (report in German). German historian of the energy sector Joachim Radkau agrees in principle that RWE was a “vehement critic” of nuclear power back in the 1960s (report in German), but at a recent event on the upcoming 30th anniversary of Chernobyl, he rejected the notion that German utilities were “forced” into nuclear. Rather, they simply asked the government for financial kickbacks. Some early nuclear reactors were built fully with governmental funding, while the state covered all cost overruns in several others.

Now, it seems that Germany might continue a version of this arrangement for reactor dismantlement and waste disposal. What other choice is there? The commission has estimated that the cost could reach nearly 170 billion euros by 2099 (report in German), and waste storage will hardly be over by then. What company in business today will even be around at the end of the century?

Covering these costs could be such a burden as to bring about bankruptcy, but propping up these private corporations indefinitely so that they don’t go bust isn’t an option either. The public will cover the cost of the nuclear phase-in one way or the other.

Some middle ground seems sensible: any profits that reactor operators post should be devoted to the nuclear fund in the amount required. And if this burden drives the one or other utility into bankruptcy, let them go – let’s not have an energy sector bailout.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.

What will it save?

http://www.dw.com/en/reports-fessenheim-nuclear-accident-played-down-by-authorities/a-19093477

A revenge for treaty of Versaille – eeh – for Fessenheim?

The cost of the waste disposal and decomissioning is deliberately inflated by appointing incompentent ideologues to key positions. For instance, we have a landscape gardener (with diploma in urban planning) heading the federal radiation protection agency. Imagine having a die-hard Jehova’s witness appointed to lead the supervision of hospitals. Would you be surprised if he blatently abuses his position to try and eliminate devil’s work such as blood transfusions and operations for good?

Now we have the Endlager-Comission which seems to be tasked with absolutely making sure that there will be no final waste repository. They spend several hour long meetings talking about political processes and not about physical solutions.

The target by which nuclear energy is measured is that under no circumstances should anyone ever come to harm from the operation of the facilities and their waste.

Civilian nuclear power in Germany has met this target with distinction, while pollution from German coal plants kills 3000 people each year through normal planned operation. They also contribute greatly to global warming, which is a threat to the entire biosphere. But the SPD and the HBF love coal, so this must be a price worth paying for saving jobs in the coal industry.