Germany’s energy transition is mainly one thing: an electricity transition. Little is happening with transportation and heat. Now, the German government has proposed new rules for cogeneration. Craig Morris says the reception can be summed up in one word: disappointing.

Municipal cogeneration plants aren’t only efficient, they can also look elegant, as this plant in Swabia proves. (Photo by Bene16, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Cogeneration is a great idea for two reasons. First, efficiency – while oil-fired boilers can have efficiencies exceeding 90 percent, you then still have to generate electricity. Roughly 2/3 of the energy input into central station power plants goes up the cooling tower unused as waste heat. As a result, the separate generation of power and heat has an overall efficiency of around 55 percent. Cogeneration units bring that number close to 90 percent.

Second, cogeneration can strengthen energy democracy. Cogeneration units are generally relatively small because heat losses are too great across long distances. Municipal utilities can run plants of such sizes, so the market would shift from corporate power providers listed on the stock market (and primarily serving shareholder value) to smaller entities that theoretically primarily address community needs.

Second, cogeneration can strengthen energy democracy. Cogeneration units are generally relatively small because heat losses are too great across long distances. Municipal utilities can run plants of such sizes, so the market would shift from corporate power providers listed on the stock market (and primarily serving shareholder value) to smaller entities that theoretically primarily address community needs.

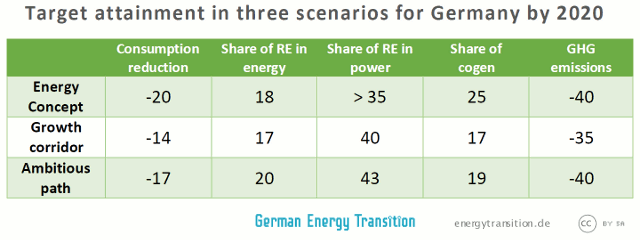

Germany has a target of 25 percent electricity from cogeneration by 2020. Unfortunately, that target currently seems out of reach. In fact, the level has stabilized at around 17-18 percent since 2010. So the government made some proposals in August towards increasing the share of cogeneration in power supply (PDF in German).

A study from this summer investigated current German energy targets along with two scenarios. Cogeneration growth did not look good in either (source article).

Under the new rule, new cogeneration units would have to be fired with gas; coal would be ruled out. A bonus would also be paid so that existing units running on coal could be retrofitted for a switch to gas.

Up to 1.5 billion euros per year would eventually be spent on electricity from cogeneration units, up from about 750 million at present. The average German monthly power bill would then rise by almost a euro to about 85 euros. As with the renewable energy surcharge, energy-industry will be largely exempt from the rising cogeneration surcharge. Nonetheless, industry complains that the proposal will make German firms less competitive (report in German) – but as always, smaller firms are less exempt, so they will once again cross-subsidize bigger industrial companies.

Industry reps also argue that the potential within industry is left unused – and they are right. Electricity consumed directly will not be eligible for any compensation except in energy-intensive firms and mini-cogeneration units, which can be used in residential units. Ironically, some firms will therefore have to pay the cogeneration surcharge for electricity purchased from the grid even though they cannot receive it for the electricity consumed in-house from their cogeneration unit (press release in German). In addition, the rates offered will be cut for small cogeneration, such as the units used in residential complexes and small businesses. The goal of these reductions is to have these generators react better to price signals from the power exchange. Note that there are no such signals for small units (mini-cogen is defined as smaller than two megawatts in Germany), only for larger generators – a conundrum the current bill does not address.

One goal of this bill is to offset an additional 4 million tons of CO2 emissions by 2020 – but critics point out that Germany has to fill a gap of up to 80 million tons. The German chapter of Friends of the Earth (BUND) also cannot follow the government’s math; the environmentalists do not believe that the proposals will reduce emissions by 4 million tons (report in German).

Perhaps the most surprising thing was that the first draft published did not reiterate the target of 25 percent, leading numerous readers to assume that the goal had been officially abandoned. The updated version from August 28 now begins with a clear statement of commitment to that very target. The bill is to be discussed in the Cabinet this month before being passed on to Parliament. It could become law on January 1 next year.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.

Dear Craig,

the cogeneration in Germany suffers from the fact that there is no decoupling of electricity generation from heat generation due to the lack of storage. As long as the co-geneartion is heat-led it may produce more problems than it solves in high RE scenarios and, therefore, I do not see the need for an increase in current structure and my feeling is your critique should be different.

Even proponents of co-generation see some clear issues, e.g. in the study published by the Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie.

“Potenzial- und Kosten-Nutzen-Analyse zu den Einsatzmöglichkeiten

von Kraft-Wärme-Kopplung (Umsetzung der EU-Energieeffizienzrichtlinie) sowie Evaluierung des KWKG im Jahr 2014”