E.ON, one of Germany’s two biggest power providers, announced over the weekend that it plans to sell its conventional power plants and focus on renewables, the grid, and “customer solutions.” Craig Morris says the real message has been overlooked.

E.ON’s management presenting their historic decision to split up the company in order to avoid further losses in the conventional power market. (Source: E.ON)

What does Germany look like to a conventional utility? Judging from recent news, you might think it seems to be an uninteresting market – maybe even scary. Certainly, utilities around the globe are looking to Germany with trepidation. Will the transition to renewables spell doom for utilities in general?

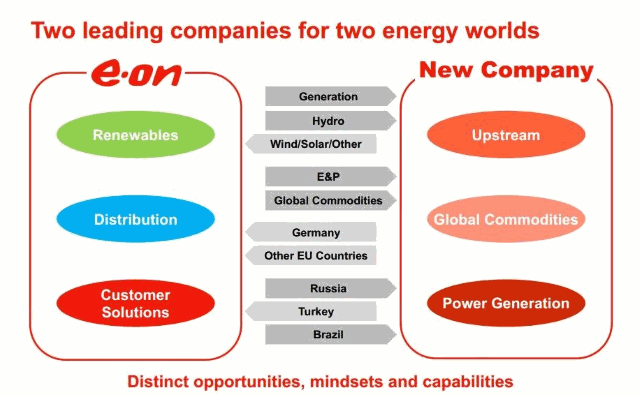

How E.ON depicts its own new strategy. The new company is on the left; what will remain of the old, on the right. Source: E.ON.

Eon’s announcement could hardly be more radical. The firm plans to put the future, which it hopes will be profitable, in one firm and the past, which is currently unprofitable, in another:

- It is divesting entirely from Spain and Portugal. These assets have apparently already been sold. It is also looking into stepping away from Italy and the North Sea.

- Its power generation assets are to be spun off into a separate publicly listed company. Essentially, this is the kind of bad bank that has been proposed for coal and for nuclear, except that this one will be investor-owned, not a ward of the state (at least, not initially).

- The focus on “customer solutions” reflects the idea that utilities will need to be enablers for the paradigm change from customers to prosumers. It remains to be seen whether large utilities are needed, say, for smart homes (SMEs can easily provide such services), but this is at least an area where utilities have a chance of making money.

- The decision to focus on distribution lines goes in the same direction. These are the lines connected to retail customers, so we are talking about smart grids, smart homes, etc. here. Note that, by EU law, E.ON is prevented from investing in high-voltage transmission grids, but not low-voltage distribution lines, as long as it generates power as well.

- The focus on renewables within power generation will mean that E.ON will indeed continue to produce power, so the transmission grid remains out of bounds. In all likelihood, E.ON aims to build utility-scale solar plants and wind farms, but we have no details yet.

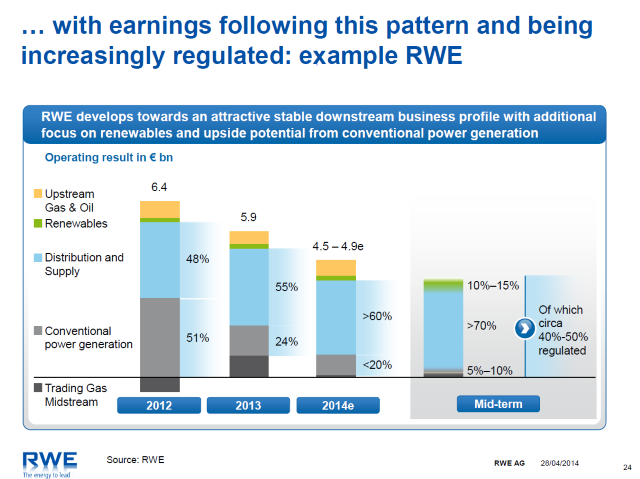

To understand the reasoning, we need look no further than a presentation given by the head economist of RWE, E.ON’s biggest competitor, in April.

If I take that chart seriously, I would divest from conventional power generation (expected to fall from 51 percent of earnings in 2012 to less than 10 percent in the next two years) and invest in distribution and renewables. It looks like E.ON has just taken RWE’s advice. It also looks like earnings are about to be cut in half for the long-term, and half of that amount will be “regulated,” meaning both guaranteed and unresponsive to corporate risk-taking. In other words, just do what the government says, and you will make a certain profit, but there’s no longer a playground for risk-takers.

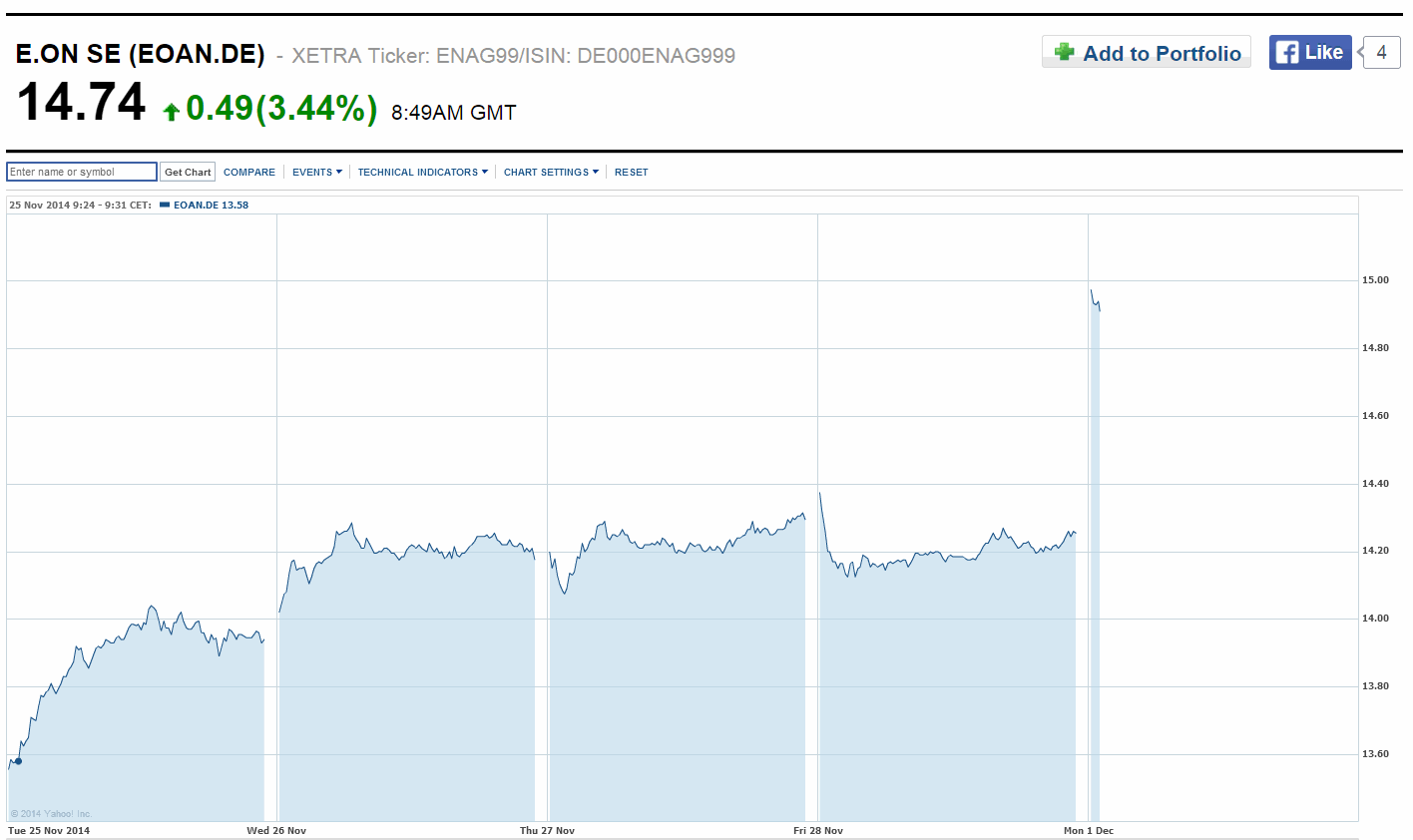

The stock market seems to think E.ON is doing the right thing. Trading ended at around 14.2 euros per share on Friday but leapt up to nearly 15 euros when trading opened on Monday morning.

Source: Yahoo! Finance

As E.ON puts it in its press release, 2014 is “the first [year] in some time in which E.ON has enlarged its customer base in Germany.” So maybe E.ON should be praised for bravely adopting a new strategy that it is already beginning to successfully implement.

But read between the lines, and E.ON is commenting on the business environment in the German power sector. Over the past few weeks, there have been intensive discussions between the government and the utility sector. There have also been calls for a coordinated shut down of numerous coal plants, for which the utilities affected might be paid. Utility lobby group BDEW also wants capacity payments in addition; essentially, dispatchable power plants would be compensated for readiness, not just power production,

The way I see it, E.ON just expressed its exasperation. The next nuclear plant to be shut down is one of E.ON’s, and months ago the firm announced it may decommission it eight months early when it is ramped down for refueling in the spring. It seems to have no confidence that the German government will protect its profitability. And why should it? The discussion in December was a roller coaster ride, just as the nuclear phaseout nuclear policy was in 2010 (reversal of the 2002 phaseout) and 2011 (new phaseout). Indeed, the nuclear phaseout hurt E.ON the most, so it’s not surprising to see the firm take such radical steps first. But I will have to provide those details in a future post.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.

They’ve probably studied Kodak. Finally.

Interesting development. What will the names be? e.ON and e.OR… Funny but too confusing. In the past the names have been synthetic. Perhaps here they’ll shoot form something with some warmth or perhaps history.

It will be interesting to see where the new company comes down on capacity payments. I figure this new company would likely lose in a world with capacity payments… i.e. They’d fight for a different policy. We’ll see.