Critics of the Energiewende suggest that Germany will eventually have to change course. But as Ben Paulos shows, the Energiewende is firmly anchored not only in German society but also in mainstream politics and the administration.

In a recent posting, John Farrell of the Institute for Local Self Reliance lays out three clear drivers for why Germans are going renewable at all costs. He lauds their focus on bills (rather than rates), a clear long term energy policy, and the widespread participation in the energy economy facilitated by feed-in tariffs.

Another side of the coin is what the politicians think of the energiewende. Critics abroad seem convinced that German leaders will come to their senses and change course on energy. Based on what the leaders say in their official documents, these critics are likely to be disappointed.

First, some background. There are two federal ministries responsible for energy, the Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) and the Ministry of Economics and Technology (BMWi). Until the recent election these were headed by Peter Altmaier and Philipp Roesler. (Rosler has resigned due his party’s loss in the recent election.)

With near unanimous support, the German parliament adopted legislation in 2010 that sets ambitious targets for carbon reductions, renewable energy and energy efficiency, and commits to a phase-out of nuclear power. According to Altmaier, the environment minister for the Merkel Administration, “this is unprecedented and brings to an end decades of public debate in Germany.”

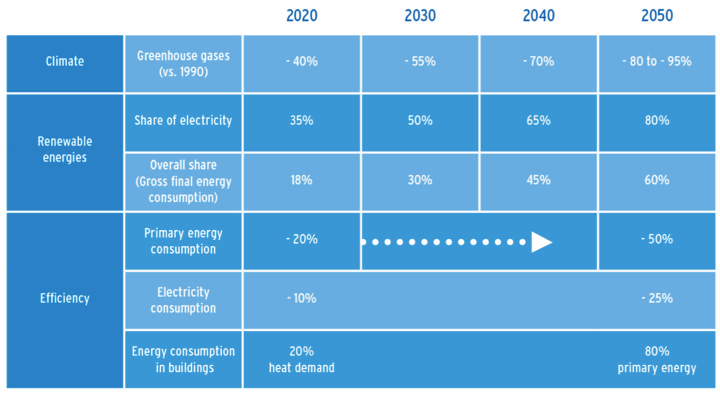

While much international attention is paid to the rapid growth of solar energy and the phaseout of nuclear power, the legislation is a comprehensive energy policy, covering transportation, heat, and electricity use across the whole economy.

German Energy Policy Goals

Now that the political debate about whether is over, the issue now is how. Most of the debate hinges on how to minimize costs.

“The bulk of our energy is to come from renewable sources by the middle of the century,” writes former economics minister Philipp Roesler. “At the same time, Germany is to remain a competitive business location. This requires a complete restructuring of our energy system.” With typical German practicality, member of parliament Hans-Josef Fell has said, “This is not a problem, it is a task.”

What’s the Rush?

While many countries have clean energy goals, Germany has gone farther and faster than most. What motivates German politicians to move so aggressively?

In official publications, Altmaier and Roesler’s ministries have laid out “five good reasons for transforming our energy system.”

1. Responsibility for the future

“A policy of responsibility for the future, policy that also takes account of the interest of our children and grandchildren, means that wherever technologically and economically feasible it is our duty to choose an alternative form of energy supply.” The multiple meltdown at Fukushima, only six months after the adoption of the German energy policy, compelled the Merkel Administration to close seven nuclear plants right away and phase out the nine remaining plants by 2022. The anti-nuclear movement in Germany is strong, motivated by the Chernobyl disaster of 1986 – less than 800 miles from Berlin – and perhaps by a lingering distrust of authority from the days of the Nazi regime.

2. Protecting the climate

Germany has committed to reducing carbon emissions 40 percent by 2020 and up to 95 percent by 2050, economy wide. Transforming the energy system enables Germany to capture the “positive dynamics of renewables and a modern energy infrastructure.” In other words, getting ahead of the challenge allows for an orderly transition and plays into German strengths in technology development, manufacturing, and export.

3. Supply security, competitiveness and cost stability

Germany imports 97 percent of its oil, 90 percent of its natural gas, and two-thirds of its hard coal. Europe is expected to increase total energy imports from 53 percent in 2010 to 70 percent in 2030. Increasing competition for energy from emerging economies like China and India, coupled with limited supplies, “are good reasons to develop new energy sources,” according to Altmaier. With increasing global demand for energy, German industry will face greater competition, higher prices, and less stability. By setting long term energy policy, the government can create “planning certainty for industry.”

At the same time, “in a highly industrialized country energy not only has to satisfy the high demands of industry and be available in sufficient amounts at all times, it also has to remain affordable.”

The main policy tool for renewable power, the feed-in tariff (FIT), pays renewable producers a fixed amount for 20 years. This predictability results in low financing costs, which lowers the cost of capital-intensive renewables. The tariff prices are adjusted down as technologies mature to reduce total costs. As renewables scale up, there is an ongoing debate about the evolution of feed-in tariffs. New solar tariffs are less than the retail price of electricity, making it more attractive to self-generate than sell into the grid. Some technologies are in the process of “graduating” from the FIT market to the competitive wholesale market. Already, about half of renewables are sold through the power exchange, including 80 percent of onshore wind.

While the Merkel administration is keen to lower costs, they have shown little inclination to back away from the goals.

4. Growth and new jobs

Like many countries, German energy policy is an arm of their industrial and competitiveness policy. Major corporations like Siemens and BASF, along with many smaller companies, are selling clean energy technology around the world. A strong domestic policy is a good way to give these companies a local market to incubate new technologies and experience. Jobs in renewable energy have grown 129 percent since 2004, employing over 370,000 people.

5. Greater public participation

As John Farrell points out, German energy policy is explicitly encouraging citizen investment in renewables. Over half of renewable energy projects are owned by individuals and farmers, amounting to over $100 billion of investment. This shares the wealth, but also creates important side benefits. German energy policy is strongly pro-competition, as power markets have been deregulated since 1998. Citizen ownership has taken a 20 percent bite out of utility market share, creating a major form of competition.

Energy investment helps keep rural Germany vital too, maximizing economic development and reducing controversy over siting new projects. Like in the US, crop subsidies can only go so far in alleviating rural poverty. And considering that Germany was reunited less than 25 years ago, the government may be hoping that the energy transition can mend the fabric of the nation. “It is a chance for our society to come together in a unique joint action,” writes Altmaier. “It is a major joint national project.”

By Bentham Paulos, Project Manager, America’s Power Plan.

I am an American ex-pat Army vet residing in Germany for decades. I have been “outsourcing” for Gertman industries – and sustainability ever since the first solar heat, solar voltaic, and wind systems started going up in the country in the early 80s.

The late Hermann Scheer, the S.P.D. MdB primarilly responsible for drafting the 1st set of Renewable Energy Laws under the Red-Green coalition under Cerhard Schroeder- also stressed the long term savings in fossil fuel purchases- as key, driving economic factor. Scheer also predicted point 4 – that “sustainability” would become the key sector in the German Gross National Product. That happened in 2011 when the “sustainability sector” outpaced the automotive sector to become the largest sector in the G.D.P., i.e. 12%, expected to grow to 20% by 2020.

The Stadtwerke München, SWm; Munich city utilities, are aiming for 100 % renewable-sustainable in its power generation and district heat facilities by 2025. They are well within the timetable, generating more tha n 50% of their power with waste to power, and renewable energy systems, and redistributing over 500 mWh of locally installed, private rooftop solar in addition to its own facilities.

I also advisedly note that o ver 50% of the energy transition is not achieved by renwabls, but a broad synergy of different “energy efficiency measures” which also sell quite well abroad.