In the first of a two-part report, Josh Matthews explains why the onus is now on the EU and UK governments to forge a global alliance for renewable energy. Part two will explore the incoming Labour government’s plans for Great British Energy, and why a just transition will need more targeted and aligned policy. Josh Matthews reports.

(Photo by Abby Anaday on Unsplash)

The far right failed to gain significant political power in Europe this summer. But there has been a troubling rise in its support in Britain, the European Union (EU), France, and many other nations, which means it will exert greater influence – whether official or indirect. France and Germany also look set for policy deadlock. It therefore falls to the new UK and EU parliaments to find a higher level of ambition and technical competence in all policy areas, and none is more urgent than tackling the climate and sustainability emergency. The growing likelihood of a Donald Trump presidency makes co-ordinated action even more important.

A global “coalition of the willing”, with Europe at its heart, can combat these political and environmental threats. That coalition should bind together potential allies from positive political shifts in India, South Africa, Mexico, and elsewhere and navigate the mixed signals from the US and China.

A sustainable coalition can create a critical mass that helps pull the rest of the world into alignment with the Paris Agreement and all 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

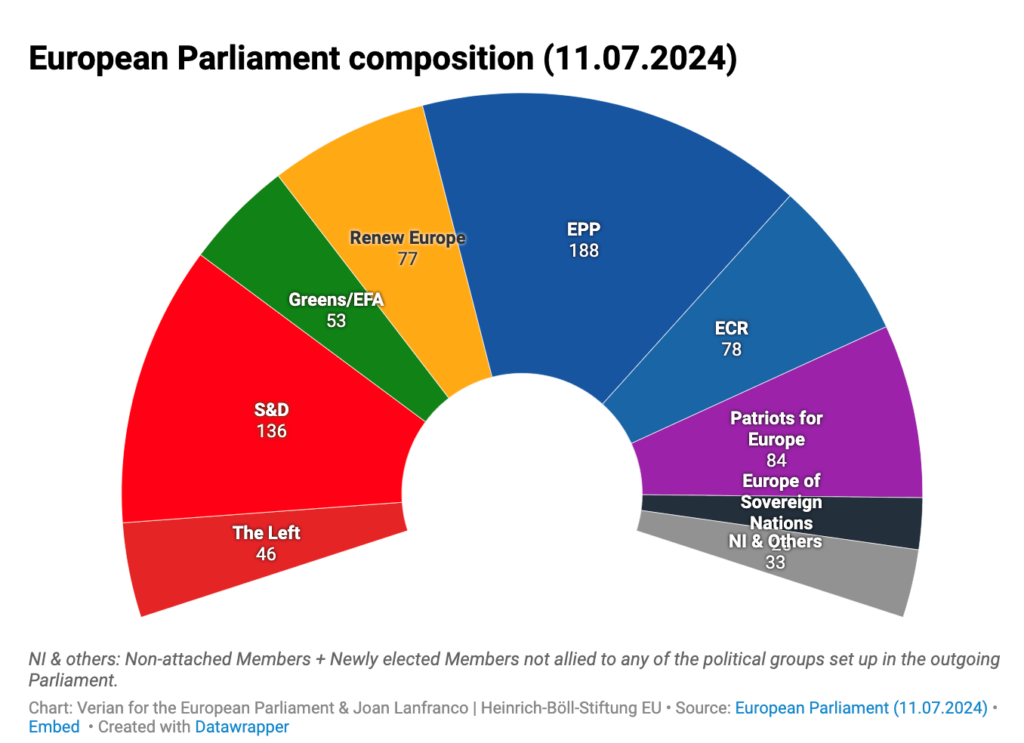

Optimistically, the European Green Deal’s climate and energy targets will probably not be watered down, given that the far right failed to achieve a majority in the European Parliament and among Member States’ governments. However, the rollout of energy transition policy now depends on Ursula von der Leyen’s centre-right political family. During the European Parliament election campaign, they suggested removing parts of the legislation that had just been endorsed under the European Green Deal. That is why it is too early to have full confidence in the EU’s direction (see Figure 1). Coalitions could prove volatile, especially as France’s parliament looks set for a three-way tug-of-war, and the US may seek allies on the right come 2025. But the EU’s centre, centre-left and centre-right alliances held up.

Figure 1. European Parliament composition, as of 11 July 2024.

A just energy transition will help the EU overcome the pressures of protectionism and climate backtracking – at home and abroad.

The US decision to impose 100 percent tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) is a mistake. The EU’s tariff (10 percent plus an individual manufacturer tariff between 17-38 percent) comes closer to accounting for imbalances in subsidies to mimic competition. But for the sake of consumers and innovation, the EU should hold its nerve.

The backtracking in Germany and France, due to the Heizhammer and gilets jaunes protests, is a reminder that transition policies can hurt the least well-off. But it has led to uncertainty and hindered the energy industry’s trajectory towards environmental, social, and economic goals – including the tripling of renewables and heat pumps by 2030 – as well as stalling, or even unwinding, anticipated green jobs growth and training.

Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) requirements, supply chain transparency, and cross-border carbon pricing have all been largely welcome additions to EU law. That leadership is also having a global effect when global companies align towards the most ambitious regional legislation.

The EU Green Deal of 2019 was a success, but there remains a great deal to do. Hints from Ursula von der Leyen that the Deal represented the pinnacle of the EU’s ambition are not encouraging. Neither is the Commission’s backtracking on a proposed heat pump roadmap.

As well as braver policy, collaboration among EU allies must extend to the new UK government.

Labour’s cautious strategy worked. But it will quickly fall apart if it does not find the ambition the country wants, and the world needs.

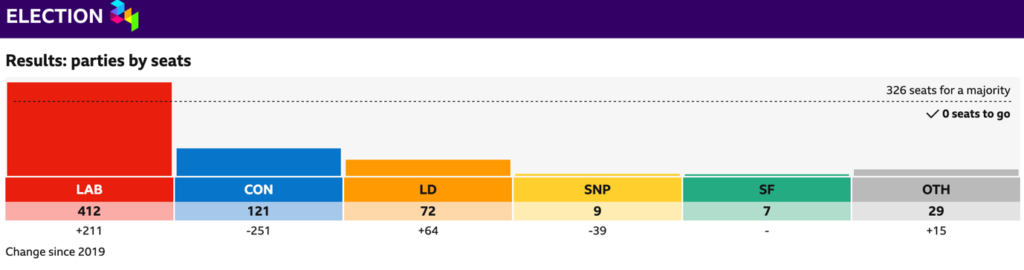

In the UK, Labour has won a historic majority (see Figure 2). But that majority is based on a risk-averse campaign and anger towards the outgoing government. In many seats that fell to Labour, the combined Conservative and Reform vote would have won. Turnout was also low. The Liberal Democrats picked up 72 seats (mostly from the Conservatives, but with safer majorities) based on positive, progressive policy on environmental, social, and economic issues. The Green Party, despite receiving at times unfair economic criticism from the media and fiscal institutes, also won four seats.

Figure 2. UK general election result, 4 July 2024

Source: BBC

Labour’s Great British Energy plan is clear about its climate ambition. But another level of ambition is needed to meet the emergency.

Labour has proposed an £8 billion investment in Great British Energy, a public investment vehicle intended to build partnerships in the energy ecosystem.

Part 2 of this report will explore the potential of GB Energy and how it could serve as a global example for a just transition. But perhaps its biggest role should be to link up the UK with the EU and other countries to encourage the mass adoption of renewables.

Global renewable capacity has tripled since the Paris Agreement in 2015, largely through policy support. The cost of solar and wind has fallen by roughly 40 percent. Clusters of countries can share common solutions to the challenges of infrastructure, technology, and financing.

Politics beyond Europe show promising signs for the energy transition – if the right leadership steps up.

South Africa’s governing coalition has a new liberal influence. Mexico recently elected Claudia Sheinbaum, a climate scientist, who may break from her predecessor’s policies. The failure of Narendra Modi in India to win an outright majority may push him in a more positive direction on all manner of sustainable policy areas. The UK and EU should seize these opportunities for collaboration. Where it is possible, collaboration with China will also require political ambition and bravery, in order to, for example, access significant economy of scale in solar panel manufacturing.

Financing remains a tremendous barrier globally. To paraphrase one attendee at the Africa Investor COP28 summit, which your author also attended: ‘Shovel-ready projects across Africa say, ‘I can’t see the investment’. While finance says, ‘I can’t see projects.’’ Policymakers can play the role of broker, as well as helping with capital, offtake agreements, and partnership confidence.

The UK, Europe, and a critical mass of allies can prove that the energy transition works for the environment, people, and economics.

The energy shocks of the last few years have made it clear that renewable energy is vital for security, stability, and social justice – alleviating fuel poverty, for example. A separate IEA report, which Part 2 will discuss, further illustrates the case for sustainability. But both affordability and fairness for all cannot be taken for granted. Upfront costs must fall on those who can most afford it. This is the responsibility of policymakers: to step in where the market will not, to harness the best of globalisation and innovation, and with the right incentives for all. The costs, capital or otherwise, must be reserved for those who can afford it right now.

The views and opinions in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union.