Zimbabwe citizens currently experience power cuts of up to 18 hours on a daily basis despite the country’s largely untapped renewable energy potential that for years could be a panacea to the enduring power crises. According to its national clean power plan, the country would have enough green energy to satisfy local demand through sources including solar, hydro, biomass, geothermal and wind. However, a lack of investment and political will has prevented most of the Southern African country’s renewable projects from taking off. Kennedy Nyavaya has the story.

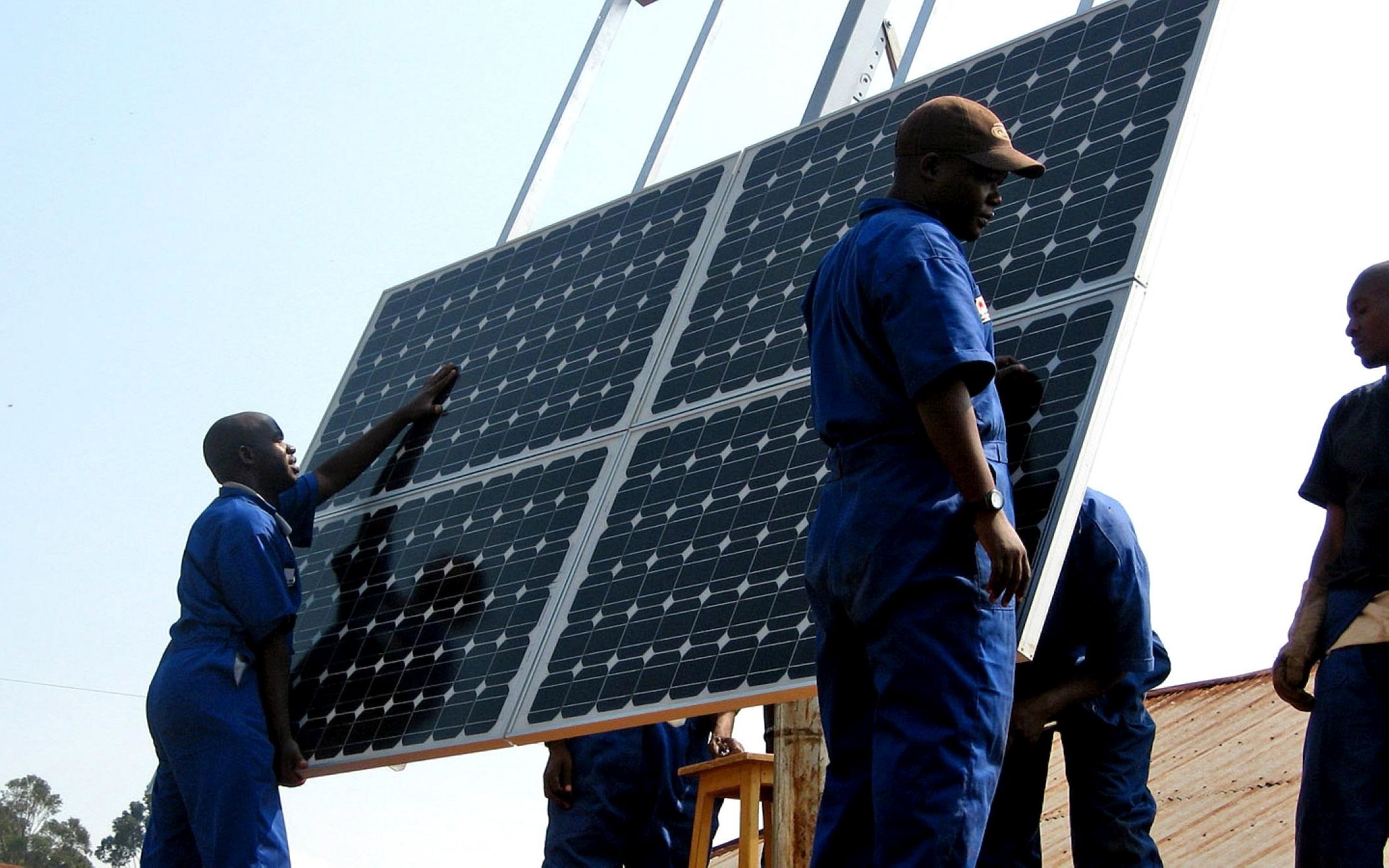

Investment in solar power installation can help stabilise Zimbabwe’s power supply. (Photo by Walt Ratterman, CC0)

In the most affluent of Harare’s suburbs, diesel-powered generators roar for hours daily while huge clouds of smoke dominate the sky in the Zimbabwean capital’s populous ghettos.

Citizens rely on alternative energy sources, mostly ecologically unsustainable ones, to deal with an immense power crisis the country has been facing, especially over the past months.

Zimbabwe mainly relies on Kariba hydro and Hwange thermal power stations for its national grid electricity, with the stations producing 1050 megawatts (MW) and 920 MW at full capacity respectively, while the remainder of electricity needs is generated by various smaller stations.

However, with Kariba Dam water levels currently at a worrying low, authorities shut down operations in November 2022 in anticipation that the ongoing rainy season will ensure enough water for power generation by January. The country is in the meantime heavily dependent on Hwange’s coal power as a result.

Still, the stations at Hwange are not producing enough power owing to many factors including obsolete equipment that keeps on breaking down. Zimbabwe is desperate for an energy solution that could ease the burden on citizens currently enduring up to 18 hours of power cuts on a daily basis.

Interestingly, the country boasts a largely untapped renewable energy potential that for years has been touted as a panacea for the power crises. With a renewable energy potential of more than enough to satisfy its needs, one wonders why the country’s main power utility Zimbabwe Electricity Supply Authority (Zesa) is currently failing to supply a paltry national grid demand of 2200 MW.

The National Renewable Energy Policy (NREP) maintains that Zimbabwe has a vast array of clean energy sources including solar, hydro, biomass, geothermal and wind. It sees this as enough to facilitate a transition from fossil fuels.

“The (NRE) Policy aims to achieve an installed renewable energy capacity of 1,100 MW (excluding large hydro) or 16.5% of total electricity supply, whichever is higher, by 2025 and 2,100 MW or 26.5% of total electricity supply, whichever is higher by 2030,” it reads.

Ostensibly, all that lacks now is investment and political will.

Unexplored potential, a case of struggling Independent Power Producers

This is not the first time in recent years that the country has faced such intense load shedding – the deliberate shutdown of electric power in parts of a power distribution system to prevent failure of the entire system when the demand strains the capacity of the system. This reality affects both households and businesses.

A lot of solutions have been mooted to end the crisis and ensure that they do not repeat in the future but, so far, they have all been theoretical.

One of the proposed solutions has been the licensing of Independent Power Producers (IPPs) with over 90 licensed so far according to Zimbabwe Energy Regulatory Authority (ZERA). The majority of those licensed are clean energy projects, although less than 10% have managed to take off and supply electricity.

But, before fingers are pointed at the IPPs for failing to establish stations and generate, there are a number of factors including frivolous government policies that contribute to their failure to make a difference.

Firstly, energy generation projects are extremely capital intensive and often the amount of capital needed is not on offer locally. This means that there is a need for foreign investment and serious government backing for IPPs to secure the much needed funding to start operating.

However, according to some IPPs, the difficulty in accessing offshore funding is related to the ability of the offtake customer Zimbabwe Electricity Transmission and Distribution Company (ZETDC) – a ZESA subsidiary- to pay for electricity supplied by the IPP and the ability of the IPP to immediately convert its income from the sales of electricity to ZETDC.

“If an investor cannot see a clear line of sight between his investment and the returns promised by that investment, he will be reluctant to invest,” Nyangani Renewable Energy managing director Ian McKersie said in an interview with this publication last year.

Secondly, while the NREP states that Zimbabwe has enough clean energy potential to satisfy a local installed grid electricity demand, government support is lagging its efforts to sustaining fossil fuel projects. For example, when the government announced the upgrade and construction of unit 7 and 8 (to the tune of US$1.5 billion) at Hwange power station – expected to add 600MW to the national grid – it was treated as a national project and constant updates were given on progress.

The same can be said about the Muzarabani oil and gas exploration project that recently started up.

However, when publicized, most clean power projects have been beset by confusion and corruption.

In 2015, the Gwanda solar project that saw government pay over US$ 5 million to local businessman Wicknell Chivhayo failed to take off owing to corrupt tendering processes, while more recently the Pomona Deal – a waste to energy project – is still facing hurdles amid reports it is scandalously over-priced and follows an unrealistic implementation timeline.

These are just a few indications that have depleted local trust of renewable energy and need to change in order to inspire local confidence in the future of renewables.

Foreign investment, tech a light at the end of the tunnel?

On paper, Zimbabwe has a comprehensive plan of how to transition into clean power use with short and long-term strategies aiming at green energy access for all and a complete fossil fuel phase out by 2050.

However, the government and other relevant stakeholders suggest that the resources and technology needed for this are beyond the reach of an underdeveloped economy.

“Firstly, equipment is imported and if investment is sourced locally one has to find the foreign currency to be able to pay the foreign suppliers and secondly if investment comes from outside the country, there is need for guarantees that the investor will get back his money when he wants it, (or) receive his return whether interest or dividends,” Renewable Energy Association of Zimbabwe’s (REAZ) chairman Isaiah Nyakusendwa told this writer.

According to Nyakusendwa, issues of volatility in exchange rates, IPPs holding licences for speculation purposes and not showing lucrative returns on investments are some of the issues that “tend to put off investors”.

“Projects also need to be bankable with an economic return to attract investment whether from a local or from a foreign source,” he adds.

Currently, investment in renewable energy projects is low, whilst countries like China and India are largely investing in major fossil fuel projects.

While the European Union as a source of funding has pledged to assist African countries in implementing energy transition plans in its Green Deal, this support has apparently been minimal at best.

This has left energy transition plans in developing countries like Zimbabwe in limbo as they continue to rely on traditional but dirty energy sources.