Its many manifestations give those intent on helping curb climate breakdown a spectrum of choices and models. The no-holds-barred climate activism of Letzte Generation and Just Stop Oil grabs headlines today the way Fridays for Future did a couple of years ago. But the climate movement is a broad and textured phenomenon that encompasses thousands of bottom-up groups around the world, with strategies and approaches that vary immensely. Paul Hockenos has an overview.

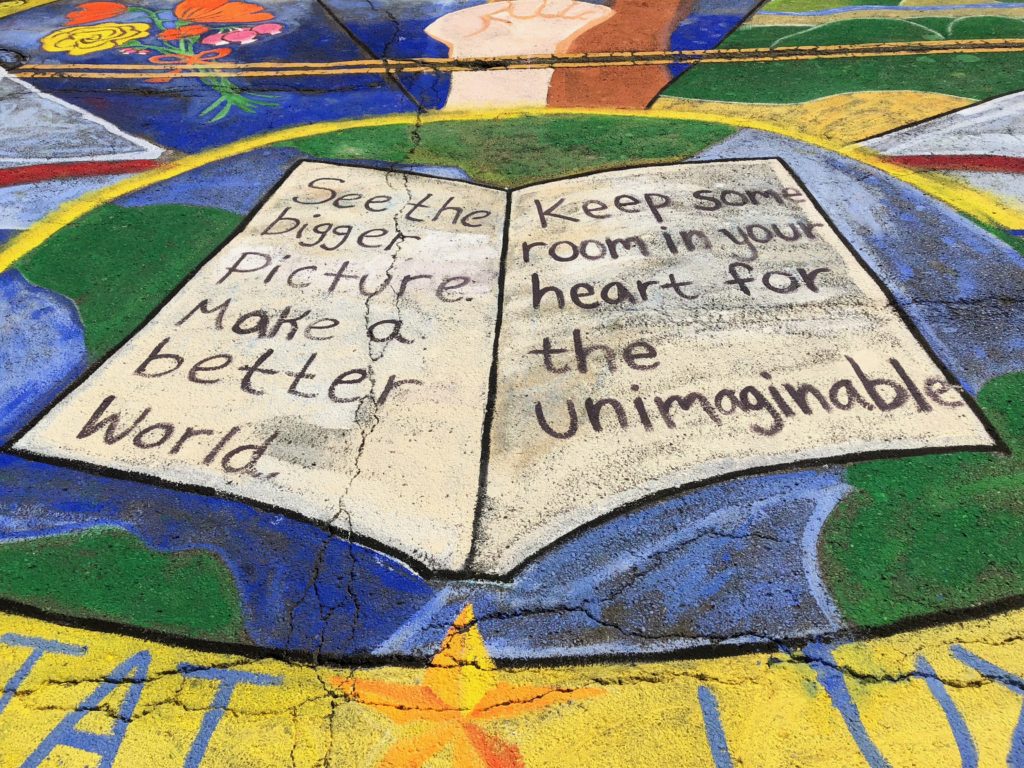

Art in the climate movement. (Photo by Fabrice Florin, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Let’s take a look at the six finalists for the Tageszeitung’s (taz) annual prize of their in-house foundation, the taz Panter Stiftung. (Panter is “panther” in English, the newspaper’s adopted symbol.) The taz is Germany’s left-liberal daily newspaper – sometimes satirical, always critically minded, never a pushover – which prides itself in the way that it combines journalism and political engagement. No media is “objective,” claims the taz, and the newspaper that grew out of the social movements of the 1970s is proud and outspoken about its subjective values, among them environmentalism and social justice. The tazler, as the staff fondly refers to itself, brought the taz Panter Stiftung to life for the purpose of bolstering basic democratic rights and civil courage in Germany and the wider world.

One of the foundation’s activities is the Panter Prize, which this year went to the most original, effective grassroots initiatives fighting for climate justice. The foundation picked six finalists from hundreds of entries and encouraged its readership to pick their favorite – two of which would receive €5,000 in prize money.

The finalists reflect just how varied and creative the climate movement is.

The Mahnwache Lützerath, an anti-coal campaign group in Lützerath – a tiny western Germany town that stands in the way of the giant utility RWE’s newest coal pit – is the contact point of the village’s neighbors: a cultural center, information hub, and café at the edge the opencast mine Garzweiler. On the periphery of the Rhenish coalfield, the project’s 15 primary members, from 17 to 69 in age, are on-the-job around the clock. Despite the nearly certain demolition of their village early next year, the cohort refuses to give up and is calling all of Europe’s anti-coal campaigners to come and help defend the village. They draw strength and hope, they say, from the massive solidarity shown to the initiative by locals and the European climate movement.

Meanwhile, SuperCoop, a collectively owned grocery in Berlin’s Wedding district, sells mainly organic products, grown and traded fairly, at affordable prices. This is only possible because its members run the shop. Passivity, says SuperCoop co-founder Johanna Kühner, won’t solve anything. Getting up and into action is the beginning of any solution, she says. One year after opening, its membership doubled to 960.

The Umweltgruppe Cottbus (Environmental Group Cottbus) is also part of the German anti-coal campaign, though located in the country’s eastern territories, near the city of Cottbus. A part of the country-wide Grüne Liga, a 1990-founded environmental group, is currently in court fighting a land expropriation case. The Nochten open-pit coal mine in the federal state of Saxony has its eyes on part of the forest. René Schuster, coal expert for the Grüne Liga, has been active in the Lausitz region against coal mining and for nature conservation since he was 15 years old. He claims that resistance across a decade has already prevented several opencast mining projects in Saxony. Yet, despite the German government’s “coal phase-out law,” residents could still be (involuntarily) resettled for the purpose of lignite extraction. “We fight for the preservation of the villages and their surrounding areas, against water crisis and climate catastrophe and for a sustainable future of the region!,” reads its website.

The Nigerian-born activist Peter Emorinken-Donatus works with the Ecocide Law Alliance for internationally effective regulation: “If we are serious about fighting climate catastrophe, ecocides must be classified as crimes,” he says. Emorinken-Donatus emphasizes that Europe has built its current economic strength through the continued exploitation of Africa. He is critical of the fact that we often look the other way when it comes to acute crises on our neighboring continent, as was recently the case with the flood disaster in Nigeria, which affected thousands of people in the Niger Delta.

And then there’s 500 AKA (500 People Active for Climate and Species Protection) that tirelessly mobilizes volunteers to create biotopes in and around Osnabrück, a city roughly in Germany’s middle. Founder Kai Behncke speaks out against forgetting “the little brother or sister” of climate change: namely, species extinction.

Lastly, Jasper Holler and Uwe Greff run a BioBoden cooperative that buys up land and leases it to farmers who practice organic farming. Their goal is to “protect as much soil as possible. As we all now know, soils are an important CO2 reservoir, whose importance even exceeds that of forests.” It’s made possible by 6,500 coop members who kick in €1000 a piece. Thus far, the initiative has bought and leased 4,500 hectares of farmland.

As it happened, BioBoden and Peter Emorinken-Donatus won the prizes – but they opted to share it with all of their co- finalists.

More than anything, it’s the experience of these people’s commitment and ingenuity in the face of the climate crisis that packs a punch. Their activism is every bit as important as that of Letzte Generation and Just Stop Oil, but they don’t grab the headlines – yet.