Inadequate primary healthcare facilities, including lack of access to electricity and health personnel in rural areas, poverty and bad roads, are among the factors fueling maternal and infant mortalities across Nigeria. Samuel Ajala looks closely at the need to provide sustainable energy solutions in primary health centres.

Signpost of Bethesda Primary Health Centre, Utabiji Ainu, Benue State. (Photo by © Samuel Ajala)

From dusk to dawn, when no sunlight was visible, Helen Ode, 34, a farmer who lives in Iga Village, Oju Local Government, Benue State, went into labour.

Fig. 1: Helen Ode with his son. © Samuel Ajala

She was rushed to Bethesda primary health centre in her village for her child delivery. “I went into labour one night and was taken to the primary health centre.”

Mrs Ode was not attended to immediately because the midwife was not around. When the midwife came, she was delayed again for three hours because there was no means of electricity for her child’s delivery. “We waited for a long time before the nurse showed up. When she came, we had to look for light until it was too late for me to deliver the baby myself.”

She was then transferred to a general hospital about 5 kilometres away for a cesarean section after over six hours of delay.

“I was later taken to the general hospital, where I was operated on. I could have given birth by myself if there was light before they could bring local lanterns from my house. I was already weak, and they had to operate on me. That was my fourth child, and I delivered through cesarean section,” she retorted.

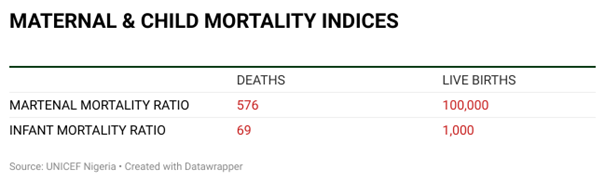

Nigeria has one of the world’s worst maternal and child mortality indices. The country’s maternal mortality ratio is 576 deaths per 100,000 live births, according to the latest data from United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). The current infant mortality rate is 69 deaths per 1000 live births.

Fig. 2: © Samuel Ajala

Woman forced to deliver through an operation because of energy scarcity

Lydia Ogar, 48, who lives in Oruoru local community, Oju Local Government Area (LGA), Benue State, was persuaded into believing she could give birth to her second child by herself at home.

Figure 3: Lydia Ogar. © Samuel Ajala

During labour, when she became weak and could barely push, she was rushed to a primary health centre in her village. “I didn’t know that I could not do it myself. I gave birth the first time myself, but this time. We opted for the hospital.”

Unfortunately, Mrs Ogar, who was supposed to undergo a cesarean section, couldn’t give birth in her local community primary health centre because there was no light.

“On getting to the Utabiji primary health care where they help people give birth, the nurses tried, and they knew that I could not make it myself, so they opted for an operation.

“But there was no light. No power supply, and we waited a while until the generator was switched on. The rain had fallen on it the previous day. That was how we left for the general hospital in Oju where I was operated upon.”

She was transported during child labour to another community of 5 km, plied on a bad road to deliver a baby boy.

“It was so painful to be transported in labour combined with the Bad roads. It was a bad experience for me. The local people did nothing except tell me to push,” she retorted.

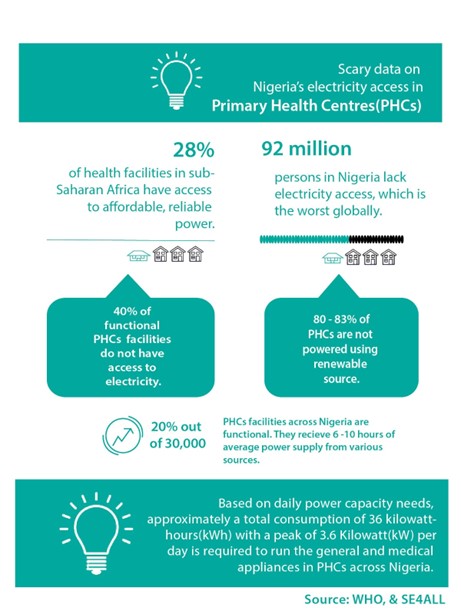

Scary data on Nigeria’s electricity access in PHCs

Based on the World Health Organization (WHO), only 28 per cent of health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa have access to affordable, reliable power. In Nigeria alone, about 92 million persons out of the country’s 200 million population lack electricity access, the lowest access globally.

Fig. 4: © Samuel Ajala

According to Sustainable Energy For All, 40% of functional primary health centres (PHC) facilities do not have access to electricity, and 80–83% of PHCs are not powered using renewable sources. The report says, “Although 40% of health facilities have no access to electricity, majority of PHCs still have unreliable access to electricity from any combination of electricity sources.”

Only about 20 per cent of the 30,000 PHC facilities across Nigeria are functional. They receive 6-10 hours of average power supply from various sources. Based on daily power capacity needs, approximately a total consumption of 36 kilowatt-hours (kWh) with a peak of 3.6 Kilowatt (kW) per day is required to run the general and medical appliances in PHCs across the country.

How can clean energy sources alleviate energy poverty?

Key stakeholders in the energy space have identified that there is a nexus between energy access and health care.

A clean energy source that is renewable via off-grid (stand-alone and mini-grid) solutions is a dependable one that is reliable to electrify healthcare facilities and actively encourage economic growth.

In locations where power is limited, especially in isolated rural areas, renewable energy supplies health clinics with effective, affordable, reliable, and independent sources of electricity. This has the potential to significantly improve healthcare access and delivery.

Interventions to provide sustainable energy solutions in primary health centres

National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) and Renewable Electrification Agency (REA) have important roles in the resource mobilisation and coordination required to provide sustainable energy solutions in primary healthcare centres in Nigeria.

The Federal Government flagged the PHCs revitalisation programme in January 2017. Under which is committed to refurbishing 10,000 PHCs across the country with at least one centre in Nigeria’s 109 senatorial districts.

To power 10,000 PHCs in the next five years and keep power solutions operational for 15 years, it is estimated that for a minimum sized system of 5kWp, a total of $525m (Capital Expenditures of $300m and Operative Expenditure of $225m) would be required over the next 15 years. This excludes project development and technical assistance costs.

Importance of sustainable energy for health centres

In an exclusive interview with EnergyTransition, a medical doctor and international development consultant outlined how lack of electricity affects pregnant women in rural areas during child delivery. They urged the government to develop policies that will reduce maternal mortality and ensure universal health coverage with access to sustainable energy.

Ifunanya Igweze, a medical doctor, said giving birth without electricity is very scary. She said it could result in pregnant women dying from postpartum hemorrhage when the bleeding point is not identified.

The reproductive health specialist urged policymakers to prioritise primary health centres by sponsoring bills to improve maternal health in rural communities. “More men and women actively into reproductive health advocacy need to stand up to influence politics and lobby themselves into the system.”

She said if the government wants to tackle energy scarcity in rural areas, it should invest in clean energy like solar power. “Solar energy is the best means the government can embrace to provide universal health coverage to the local areas.”

Damilola Balogun, youth delegate for Africa-Europe Foundation at Sustainable Energy For All (SE4All), recognised that the hallmark of life is energy and its importance. He said expanding energy access to rural communities will help address the frequency associated with lower odds of safe birth delivery in health care centres.

“To emphasise, due to the lack of adequate electricity supply in rural healthcare centres, certain medical equipment does not function when needed, thereby increasing a woman’s odds of not having a safe birth delivery.”

The international development consultant urged the Nigerian government to develop policies that put the energy issue at the heart of developmental strategies. “Finally, international development agendas are centred on people’s right to sustainable development, poverty eradication, and good health care systems.

“The forerunner to achieving this right is widespread access to secure, affordable, and reliable energy, and to substantially enjoy this right, the role of government cannot be overemphasised,” he ended.