New studies are sanguine about emissions-free and carbon neutral aviation in the near(ish) future. But rosy projections meet with justified scepticism from environmentalists. Ultimately, we’re going to have to fly less, no matter how you look at it. Paul Hockenos has the details.

Emissions-free aviation seems possible – in the future. (Photo by DLR, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

The German Aerospace Center (DLR), Germany’s research centre for aeronautics and space, has announced a strategy to achieve emission-free aviation . The development of highly efficient aircraft that use climate-friendly drives and sustainable fuels, as well as optimized flight routes, can deliver on tough EU targets, it claims.

Naturally, it’s good news that the DLR is tackling aviation as flying’s a well-known climate killer – probably even more destructive than acknowledged – and the DLR is one of Germany’s top research institutions. Moreover, if unaddressed, aviation emissions could double by 2050 and consume up to a quarter of the global carbon budget.

The DLR’s work is fully in line with EU ambitions: the next generation of aircraft must slash energy use by half by 2050. The ReFuelEU Aviation initiative proposes EU-wide rules for sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) that will apply to fuel suppliers and airline operators. Airlines, for example, will soon be obliged to tank ever more SAF-blended aviation fuel when departing from EU airports, at increasing percentages from 2030 to 2050.

“Contrary to the road transport sector,” admits the European Commission, “zero emission aircraft are not yet available on the market, and will not be widely in use before 2035 for short-haul flights. Options to decarbonise aviation are limited. It is necessary to decarbonise aviation fuels as they will remain the norm to power aircraft in the decades to come.”

This is the interface at which the DLR is pursuing its research. In terms of fuel andsufficiency drive technologies, it has three priority categories:

- Turbofan engines for long-haul routes

On short- to long-haul routes, the technology with the greatest promise at the moment appears to be highly efficient turbofan engines, basically gas turbine engines, that rely on kerosene generated from renewable sources. The switchover, claims DLR, is doable for whole fleets with negligible technical modifications to the engines and infrastructure. - Propulsion systems for medium-haul flights

Hydrogen can sink CO2 emissions in local aviation to zero, argues the DLR. In the medium term, hydrogen use is particularly suitable for regional and short-haul aircraft, it notes. But: “For hydrogen propulsion systems, volume and weight as well as integration and safety pose particular challenges.” - Hybrid-electric drives in regional travel

Batteries and fuel cells are extremely efficient, but suitable only for small aircraft and regional jets, admits DLR. Research is ongoing into high-performance electric motors, batteries, and fuel cells.

While the DLR report doesn’t downplay the complexity and challenges of getting to emissions-free flying, its conviction is definitely that it is possible. Germany’s new transportation minister, Volker Wissing, agrees at least in so far as that e-fuels are better suited for air transport than for road travel.

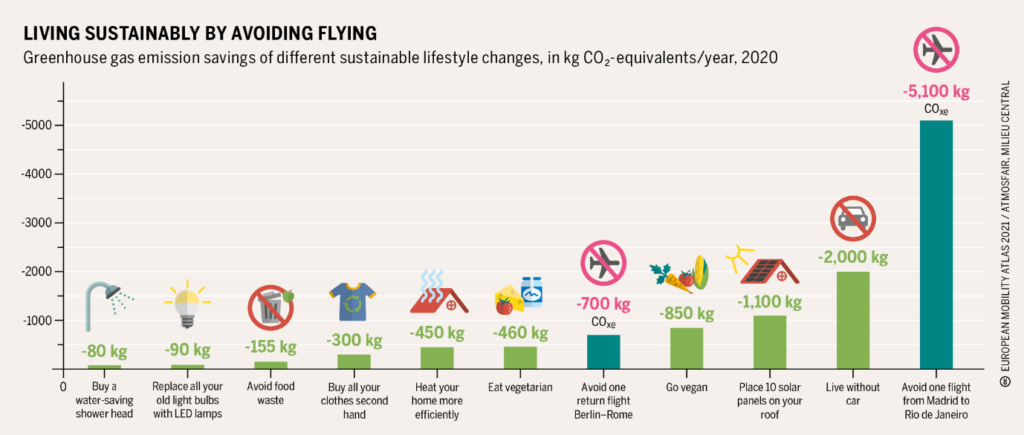

Critics like the network Stay Grounded, an umbrella organisation for about 170 initiatives around the world campaigning for a climate just reduction of aviation, are much more sceptical. They argue that the most effective short–term solution isn’t so complex: namely to cut back on flying, dramatically.

Magdalena Heuwieser, co-founder of Stay Grounded, argues that batteries and fuel cells are simply not viable, primarily for reasons of weight. As for biofuels, she notes that their production often brings accelerated deforestation, biodiversity loss, and human rights abuses. Synthetic fuel made from electricity, on the other hand, while technically feasible, is impracticable: “if all planes currently operating were to fly with e-fuels,” argues the author of The Illusion of Green Flying, “this would consume more than the existing renewable electricity supply in the world, leaving nothing for other sectors.”

Heuwieser and many climate scientists, too, thus argue that “the only way to reduce aviation’s emissions is to reduce air traffic.” They propose limits for short-haul flights, a moratorium on airport expansion projects, and a frequent flyer levy. A key demand is to end aviation’s regulatory advantages over more sustainable forms of transport, for example by eliminating its tax exemptions. Outrageous but true: kerosene is the only fossil fuel apart from maritime heavy oil that is not taxed; flight tickets are exempt from value-added tax.

Perhaps the DLR’s vision, as an option for the distant future, doesn’t clash quite so starkly with Stay Grounded’s take as it might seem – as long as we’re talking about the distant future. In the short term, though, we simply have to fly less.