Fresh EU directives have spurred new legislation across the EU to expand citizen-owned energy projects. But collective renewables still bump up against the powerful forces of traditional utilities, grid operators, and conventional energy interests. Paul Hockenos gives us the details.

A new study by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) on community renewable energy in Europe illustrates just how broadly the concept of citizen-owned energy services has been applied across the continent. As a result of the EU’s Clean Energy for All Europeans package, which confirmed that prosumers and their collective forms will play central roles in the energy systems of the future everywhere in the EU, new national legislation is currently being drawn up to make community energy possible in countries where it is hitherto unknown – and more sophisticated where it already exists.

“Community renewables” or “citizen energy” are the labels for a broad palette of collective energy actions in which citizens and communities engage as partners in clean energy projects. In community energy, climate protection becomes a DIY endeavor. The traditionally passive consumer becomes an energy prosumer. The colorful, heterogeneous projects constitute a fount of truly original social innovation that can take the form of cooperatives, associations, partnerships, development trusts, and even private companies.

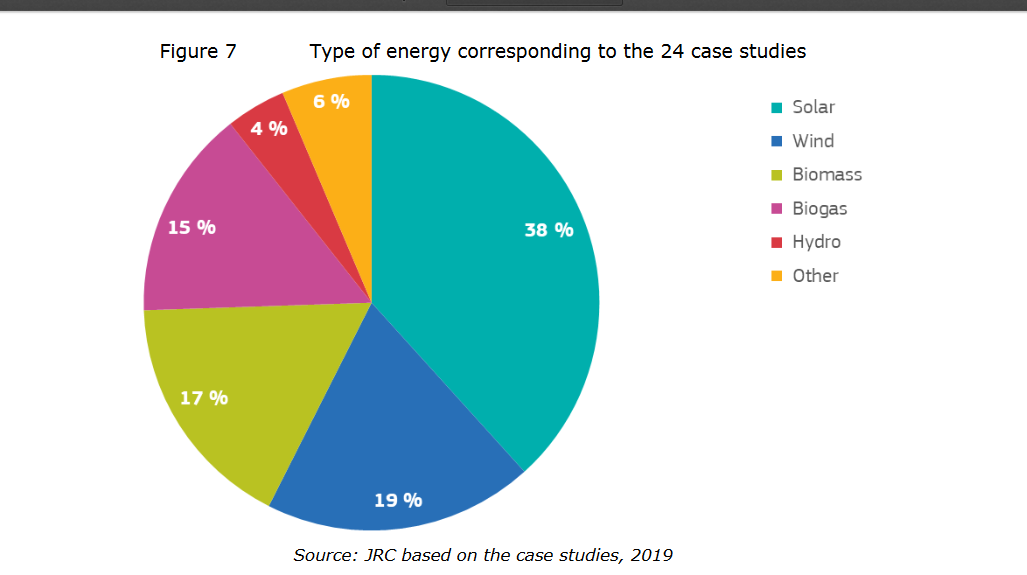

The JRC report, “Energy Communities: An Overview of Energy and Social Innovation,” is a fascinating analysis of where community energy stands in Europe today. Although the majority of community-based projects are engaged in generation — wind, solar, small hydro, bioenergy, heat pumps (see graph) — their undertakings are morphing into more complex, closely linked fields, such as energy supply, energy efficiency, energy sharing and electro-mobility. The report notes that by 2030 energy communities could own 17% of installed wind capacity and 21% of solar Europe-wide. By 2050, almost half of EU households are expected to produce clean energy.

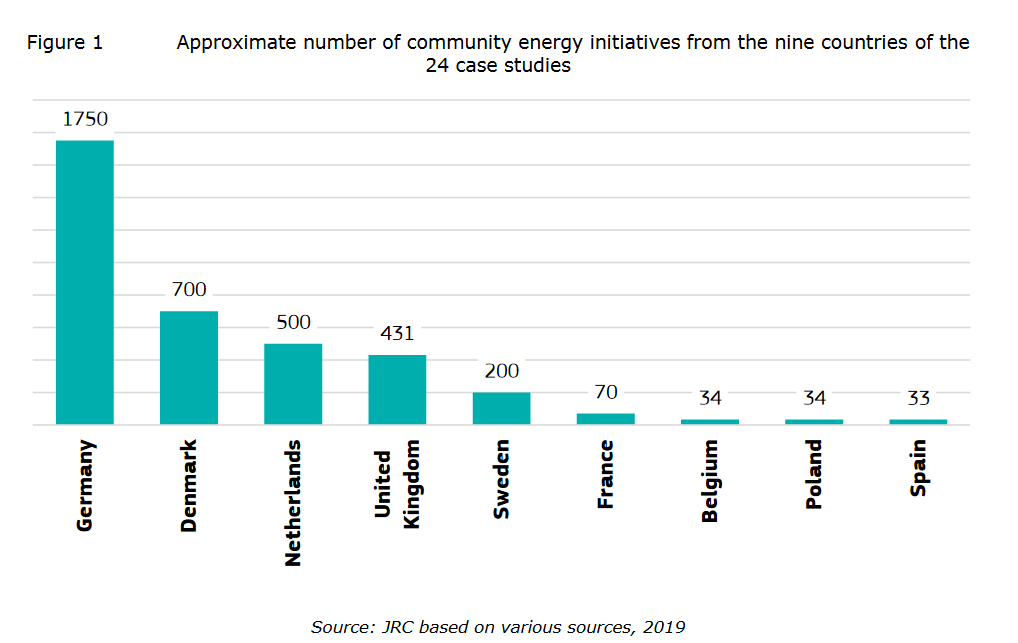

The report found 3,500 renewable energy cooperatives, mostly based in nine North Western European countries (see graphic below). This number is even higher when other types of community energy are included. Indeed, this number sticks to a more narrow definition that includes just cooperatives, eco-villages, small-scale heating organizations and some other projects led by citizen groups. Local utilities, such as the Stadtwerke in Germany, are thus not included in the aggregate number (though they should be.)

The most common citizen-energy enterprises are small-scale, decentralized energy production facilities, such as schools or farm roofs equipped with solar panels, or wind parks built by rural communities. Also there are many small biomass installations, heat pumps, solar thermal and district heating networks. What is more is that ever more of these enterprises, are also getting involved in energy services that benefit the entire community. Energy sharing and peer-to-peer energy, in German Mieterstrom, are means by which renewable energy producers distribute energy to local end-users interested in cheaper and cleaner energy. This could take the form, for example, of an apartment building with solar collectors that offers its tenants energy at cut-rate prices.

“Branching out beyond production alone is important as it addresses the criticism that what most citizen energy projects do is produce energy and then leave the utilities and grid operators to worry about the rest of the job,” says Andreas Wieg of DGRV, the federation for German cooperatives. “Energy sharing links production to consumption,” he says.

Wieg says that the German energy movement’s greatest need is laws that make energy sharing easier, which is stipulated in the EU legislation. But Germany has been very slow to get behind the idea, he says. “There’s still a lot of pushback from the utilities.” But he says the situation is not as bad as in France where the highly centralized energy system and monopolized market is even more resistant to from-below models.

The conditions across Europe should be improving for prosumers of all kinds when the EU directives are turned into law. A recent report by RESCOOP, the European federation of citizen energy cooperatives, updates the progress, showing both progress across the EU and a remarkable heterogeneity in organizational forms. But the devil is usually in the detail. While the EU directives say that the playing field should be leveled in order to enable collectives to compete on the energy markets, the extent to which this must happen and the Member States’ urge to actually implement the legislation are unclear.

Over the years, community energy projects have increased rapidly when driven by renewable energy support schemes that provide incentives. In addition to government support, their long-term sustainability, notes the EC report, will be contingent on the development of viable business models with innovative financing and remuneration schemes, the use of smart technologies, the nature of national regulatory support, and degree of citizen participation.

In the end, legislation must oblige utilities and grid owners to buy self-generated energy from the collectives, the way it has been done in Germany, says Toby Couture, Director of E3 Analytics, an independent renewable energy consultancy based in Berlin. In countries across eastern Europe, independent, decentralized producers are still denied access to the grid, through a number of means. “It’s easy to pick on Eastern Europe,” says Couture, “but France is equally guilty of this.”

“In particular,” notes the RESCOOP report, “national energy regulators will need to monitor the removal of unjustified obstacles to, and restrictions on, the development of collective energy communities.”

Let’s make sure this happens as community renewables is the way to put the global Energiewende in the hands of the citizenry – those most keen to make it happen.