The goal of 500,000 people employed in the renewable energy sector moves further out of reach every year. The trend is now embedding in wider reports of “environmental jobs,” not reported separately. Craig Morris takes a look.

Jobs in the German renewables sector are endangered (Photo by Viola/pixelio.de, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In 2000, when Germany passed its Renewable Energy Act, parliamentarian Hermann Scheer stated that the goal was partly to get German industry focused on exporting renewables (in German):

“Some types of renewable energy, such as photovoltaics, are still relatively expensive here but are already the cheaper alternative in areas of the Third World with no grid access. And if we want to do more there, we have to get the industry moving here…. We have to keep in mind… that we are an export economy.”

Scheer had come to renewables from peace policy; he understood that German manufacturers needed to make money off of something that promoted peace. Renewables seemed perfect.

But if he thought that Germany would produce systems and export them, he and many others are increasingly turning out to be wrong. Back in 2004, the German Environmental Ministry said (in German) that “400,000 people could be working in renewable energy.” It would have been a several fold increase from the 120,000 jobs in the sector at the time. The overall number of jobs in the renewables sector is growing, but from a German perspective – mostly abroad.

By 2010, the figure had reached 367,400 (PDF in German), so half a million ten years later might not have seemed far-fetched. The sector itself, at least, began speaking of this goal around 2010 (PDF in German). As the head of the German Renewable Energy Federation put it at the time, half a million jobs would make renewables “bigger than chemicals” in Germany (which is home to the world’s largest chemicals firm, BASF) (in German).

But then, in 2011, the figure peaked at 382,000 renewable jobs (in German). The German solar sector was already shrinking at the time, and by 2012 the job losses could no longer be ignored.

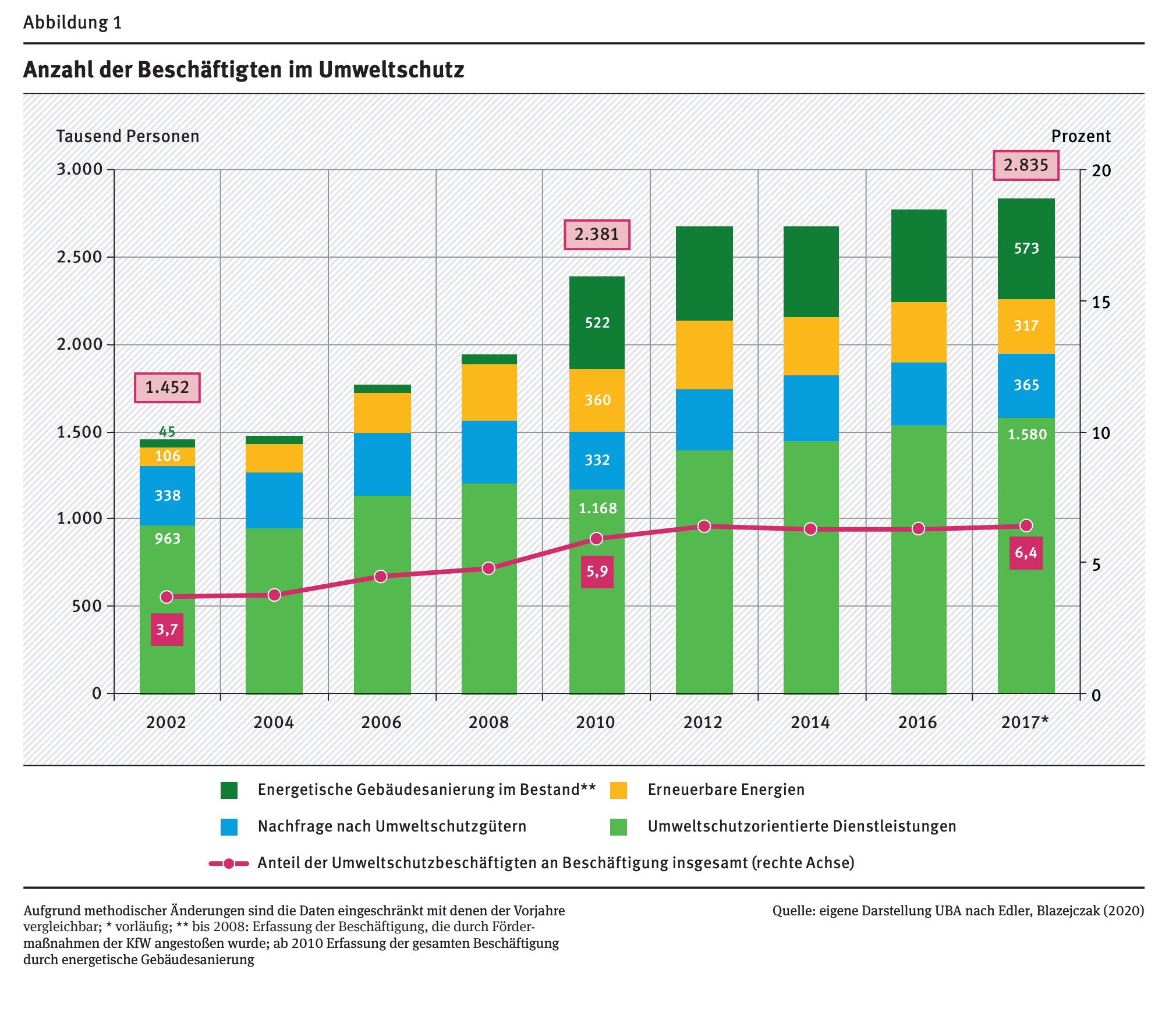

The German Environmental Ministry BMU and the Environmental Agency UBA have, at various times, reported figures either for jobs in “climate action” or “environmental protection.” In the latest report from March (PDF in German), UBA provides the following overview.

Employees in thousands by sector. From top to bottom in the bars: green = energy refits in buildings; yellow = renewables; blue = environmental goods; light green = environmental services; and the red line = share of green jobs in total employment.

The bar for 2017 shows only 317,000 people working in renewables. And the number today will be much lower. Since then, some estimates put the job losses in wind alone at 40,000, with up to an additional 25,000 at stake this year (in German).

Germany no longer has a major solar panel or cell manufacturer, and it may have been unwise to expect the country to be home to such an industry; after all, solar panels are about as high-tech as radios, which Germany also no longer makes many of (remember Blaupunkt?). Likewise, remember Grundig? “Plasma TVs” – a bit more high-tech than mere radios – was a bit of a German meme for a technology it lost in competition with Asia a decade ago. (On the other hand, who has a plasma TV today? Once again, Germany’s best engineers banked in the wrong tech #Dieselgate.)

Germany largely abandoned biogas after 2014, leaving mainly wind power. Arguably, this tech fits Germany better: heavy metal stuff that engineers continually tweak.

The problem is that the Germany wind market collapsed in 2019, and no change of course is on the horizon. The German government now mainly pursues a “hydrogen strategy”, which will give the country’s giant gas sector a role to play – which is good. Less good is the strategy’s focus on importing green hydrogen from abroad in a decade that is likely to see a net reduction in wind capacity at home, with around 2 GW scheduled to be dismantled annually in the 2020s. Only half that amount was added in 2019. The result could be less renewable power in 2030 than Germany has now.

Exports of wind power equipment continue, of course, but they will not stop the job losses at home without an uptick on the domestic market. Towers, for instance, are better made locally; blades often as well. International players from Germany can still expand on the growing international market, but those jobs will mostly not be in Germany.

For what it’s worth, the number of jobs in Germany’s chemicals sector remains stable, having risen slightly in the past decade to just over 300,000 (in German). When the figures come in for 2020, chemicals are likely to be considerably bigger than renewables in Germany in terms of employment.

The German PV manufacturing industry is seeing a strong pick-up:

https://www.pv-magazine.de/2020/04/27/solarwatt-verzeichnet-bestes-quartal/

During the lockdown SolarWatt had been flying in cells from China to keep up with demand.

Europeans incl. Germans want no jobs, they want a basic unconditional income and carbon neutrality by 2030:

https://eupinions.eu/de/text/in-crisis-europeans-support-radical-positions

The idea to be slave and to support the cane isn’t that widespread in Europe. The majority wants to live a moderate emphatic life style seeing ‘more’ not as better.

The linked Bertelsmann study is social dynamite, most German media don’t mention it.I don’t know if is published in German language, Bueckware ……. 😉