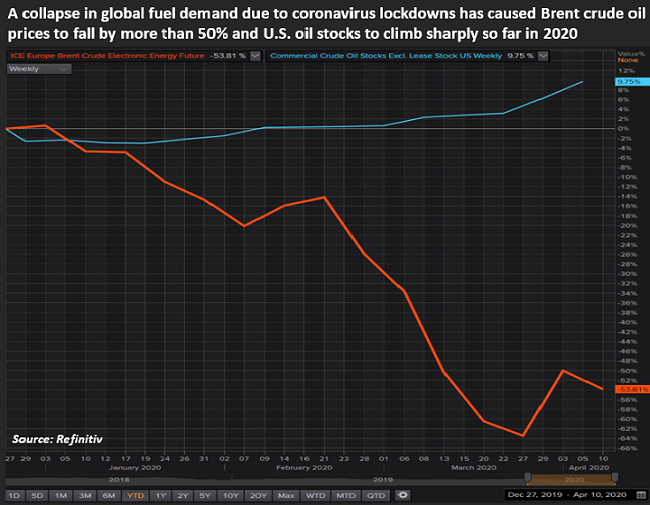

Overshadowed by the pandemic, an oil production and price war waged between the Saudi Arabian-led OPEC, Russia, the U.S. and other nations has landed a body blow upon the already weakened global economy. With billions worldwide now sheltering in place, oil usage has dropped by over 30%. But production hasn’t. The massive oversupply has crashed market prices lower than at any point in almost 20 years. To stop the bleeding, OPEC and other producers as well as the G20 have seemingly come to an historic deal that will slash global production across the boards. But the damage to the underlying fossil-fuel based economy means that Corona’s economic wreckage will ripple out just as we start to emerge into a brave new social-distance demanding world. L. Michael Buchsbaum examines the origins and implications of the Corona oil crash.

The oil industry has been struggling in the Corona crisis. (Public Domain)

Cheap oil, expensive problems

By exploiting its shale oil, the US has become the world’s top oil producer over the last decade. Fracking, the process by which oil can be extracted from underground rock formations after they are hydraulically fractured open, has revolutionized America’s economy and bolstered its global power. Riding the boom since he entered office, a major chunk of Trump’s celebrated economic bounce has literally been predicated upon fracking. Not only oil and fossil gas’ market value, but on how long industry can keep squeezing a steady stream of it out of the ground.

But fracking comes with a really high price tag. Driven by an endless petro-hamster wheel cycle of drilling, production and quick depletion – repeat, it leaves an environmental mess, including groundwater pollution and billowing methane emissions. Even measured by cold numbers, fracking is an expensive enterprise only feasible when oil is fetching much higher prices than today. U.S. producers, almost all of who require oil prices of between $30 and $50 just to break even, are being squeezed by debt, and a lot of it. Some $133 billion alone is due by 2026, according to analytics firm Rystad Energy. Indeed all throughout the shale boom, most frackers have never even turned a profit.

With their U.S. competition limping through the last few quarters, the Saudis, Russians and other government-owned oil companies in OPEC kept pumping away. Armed with “a silver bullet” capable of demolishing even the most resilient North American company, they can access vast reserves at very low costs with “the ability to flood the market anytime,” posits Chris Tomlinson in the Houston Chronicle.

A barrel of oil from an existing well in Saudi Arabia has a marginal cost of $4, according to the number crunchers at Wood Mackenzie. In Russia, Tomlinson adds, the short-run marginal cost is about $10. Compare that to Texas’ premier Permian Basin shale oil that requires $12 just to get it out of the ground, excluding the drilling and financing costs that are far beyond what OPEC and Russia pay. By comparison, virtually all U.S. shale production is 10 to 15 times more expensive. If prices stay below $30/barrel, not one of the 100 largest fracking operations in America can turn a profit.

No demand during an economic quarantine

Shutting down the industry is the very tactic being used against the virus: stopping people from moving around. But “oil is made for people to move around by cars, airlines, ships. So this war hits right on the nerve system of the global oil industry,” said Per Magnus Nysveen, head of analysis at Rystad.

Indeed, as more folks worldwide came under some form of corona-forced lockdown, plummeting demand has caused the entire supply chain of oil drilling, shipping, and refining to seize up as producers at all levels keep pumping, desperately searching for any available storage.

By the end of March, roughly a third of the oil sucked up daily by global capitalism–approximately 30 million barrels per day (bpd) out of the roughly 100 million bpd pumped– stopped being burned. “The biggest drop in history,” noted The Financial Times, it may be seven times bigger than the previous largest quarterly decline following the 2008 economic crash, according to data by consultancy IHS Markit.

As demand has crashed, so have prices. Oil hasn’t been this cheap since the beginning of America’s war against Iraq in 2003—which, not coincidentally, marks the onset of America’s shale gas revolution. Now experiencing their own shock and awe, majors like ExxonMobil, in a few weeks’ time, have seen their market valuations nearly halved.

On April Fools Day, after “Well-Street” refused to loan it more capital, Whiting Petroleum, a Denver-based producer that had made it big in the first major fracking field, North Dakota’s Bakken formation, filed for bankruptcy. Whiting’s stock—which had been trading above $150 a few years ago, had just fallen below $1 a share. Experts expect it will be just the first of hundreds, if not thousands of companies to go under.

Calling it a “game changer for the industry,” the crash will lead to widespread consolidation. But Goldman Sachs warns that after the downturn, big shale’s “capital constraints,” debt and structural disadvantages will remain.

Infographic: Crude oil prices v Wall Street’s oil stocks

Desperate Measures

Over Easter weekend, in a series of desperate, virtual meetings, the world’s biggest oil producers, including Russia, Saudi Arabia, OPEC, the G20 and the United States, agreed to slash the world’s oil output by some 15% over the next few months in a desperate bid to lift prices. Marking a truce between the “warriors”, the overall agreement may still be too shallow “to arrest the price decline,” banks Goldman Sachs and UBS predicted.

Trump himself was personally involved in the negotiations, keenly aware that measures he’s begrudgingly authorized to slow the spread of COVID-19 are hammering the price-vulnerable US shale industry. Coincidentally, America burns some 20 million bpd to fuel its economy—about what it produces.

Efforts to come to an agreement were stymied, however, as Mexico was unwilling to accept a cut of some 400,000 bpd. But in a moment of delicious irony, Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador agreed after Trump personally offered to make extra US cuts dropping Mexico’s portion down to only 150,000 bpd. Perhaps it’s truly all in the Art of the Deal.