At the end of January, the Commission on Growth, Structural Change and Employment, aka, the Coal Commission, finally released its 336-page report. Filled with economic observations and recommendations, it sets an end date of 2038 for Germany to close its last coal-fired power plant. L. Michael Buchsbaum reveals the most important facts of the report.

Agreed to by a 31-member team comprised of environmentalists, union leaders, state ministers and representatives of power companies like RWE, though weak on concrete determinations like which plants and mines should be shut and when, the report instead provides a range of goals and deadlines for how many gigawatts of generating capacity should be curtailed. But regarding the still occupied Hambach Forest, site of on-going protests and a symbol of the public’s desire for an immediate coal shutdown, the report only says preserving it “would be desirable.”

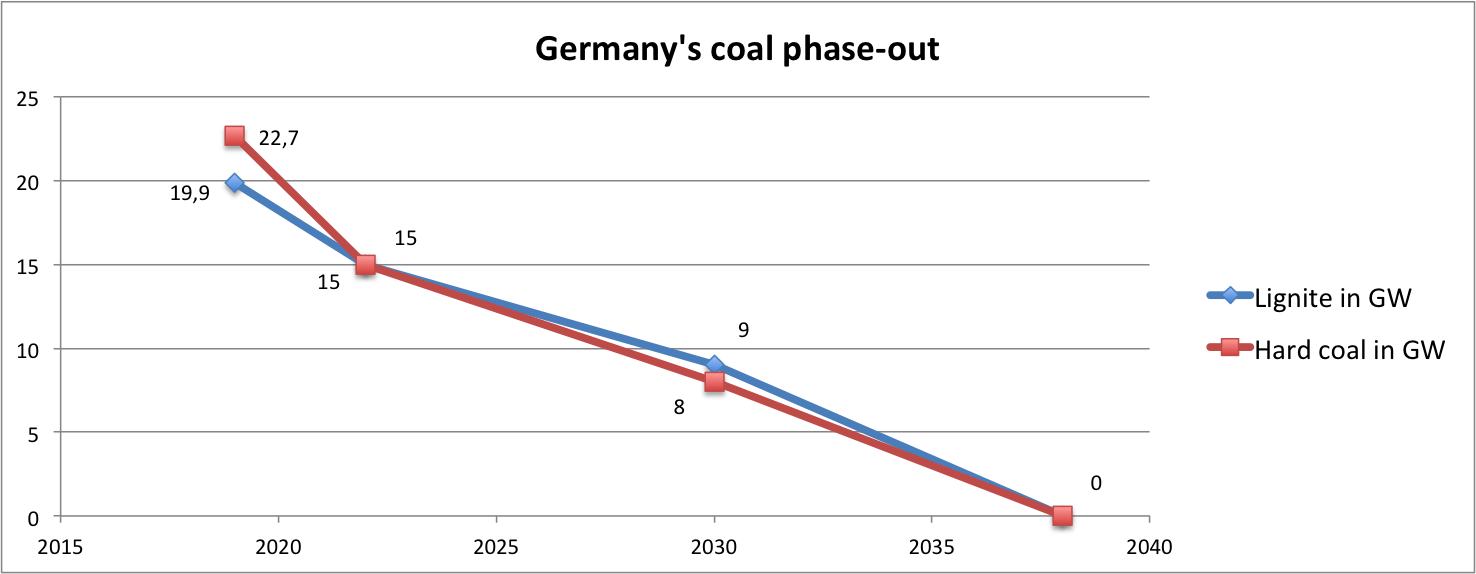

Under the terms of the plan, by 2022 today’s total coal-fired output would be reduced from over 42 gigawatts to 30 gigawatts, split evenly between domestically-mined brown coal and imported hard coal. The planned 5 GW lignite reduction means local production, most likely in the Rhineland area west of Cologne, will be curtailed. However, if you subtract the facilities that were already planned for shutdown, only seven additional gigawatts of coal capacity have been added, according to economic newspaper Handlesblatt. The coal commission proposed that an independent panel assess the announced measures in 2023, 2026 and 2029 to see whether they were delivering in the intended results with regard to jobs, security of supply and prices.

Nevertheless each committee member voted to adopt the report, except for Greenpeace’s Martin Kaiser, who criticized the coal burning end-date of 2038 as “unacceptable.” However he seemed to sum up the prevailing mood by stating that “At least Germany is moving again after years in a climate policy coma. With the help of the pressure of tens of thousands of protesters, Greenpeace and other environmental groups were able to push through important partial successes: Germany finally has a road map for how to make the country coal-free. There will be no further coal plants.”

However, even as the report’s recommendations are debated, Commissioner Antje Grothus, called on environmental activists to stay in the embattled Hambach Forest. “You just can not trust RWE here,” said Grothus on Monday to radio station WDR5. “And you have to make sure that it is protected.”

While envisioning an end to coal mining and burning in Germany, the plan notes this will come in part by converting some coal-fired power plants to burning imported fossil gas instead. Additionally, since the last nuclear reactor will also be shut down in 2022, the efforts to increase the share of green energy must be considerably increased. To avoid surcharges on the price of electricity, private households and the overall economy should also be shielded from rising energy prices and the commission considered a subsidy of at least €2 billion per year will be necessary to reduce network costs. The commission said energy customers should not face a surcharge for the phasing out of coal.

To help ease the pain of structural transition in coal regions, the Commission proposed at least 40 billion euros ($45.7 billion) in aid to North Rhine-Westphalia, Brandenburg, Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt. The commission recommended the federal government provide €1.3 billion per year over 20 years. In addition, they should provide all German states with €700 million per year over a 20-year period, and decommissioned areas should be prioritized for the further expansion of renewable energy capacity.

The report said ways to determine further compensation for power producers could include capacity tenders or simply keeping plants on standby, similar to existing reserve payments for operators that have totaled as much as 150 million euros ($171 million) per gigawatt per year in the recent past.

Compensation should also apply to plants in operation and those that have not yet entered service or were still being built, including Uniper’s Datteln 4. However, the older the plants, the lower the compensation, the Coal Commission added. Eckhardt Ruemmler, chief operating officer of Uniper, which operates 3.8 GW of coal-fired capacity in Germany, said the report suggested the Datteln 4, a 1.05 GW coal plant that has so far cost 1.2 billion euros, would never enter service.

RWE, Germany’s biggest power producer, lignite miner and the largest operator of coal-fired plants at 13.3 GW of capacity, said an end date of 2038 was too soon, urging lawmakers to consider extending this during a planned review in 2032. “We are obliged to protect the interests of our employees as well as our shareholders,” RWE Chief Executive Rolf Martin Schmitz said in a statement. Either way, German coal producers and burners will not walk away empty handed.

Calling the agreement “a good compromise for climate protection,” federal environment minister, Svenja Schulze (SPD) also lauded its economic suggestions for the affected mining regions, saying in total, the plan shows how Germany could guarantee supply security. “The commission has done a very, very good job, she told Deutschlandfunk.

However, even though the contents of the plan have now been published, they are not binding. Indeed many have suggested that the real negotiations are only now about to begin. Claudia Kemfert, energy economist at DIW, while praising the compromise warned that “it is particularly important that politicians follow the report’s recommendations. The time for excuses is over, the coal exit has to be put in action fast and the Energiewende must be advanced.”

In a first step, the relevant federal ministers will now thoroughly review the report. Federal Economy and Energy minister, Peter Altmaier (CDU), said it will “take a few days” before conclusively commenting on the proposals, he told public broadcaster ZDF. “We will discuss this with the state premiers, but also with the four commission heads over the coming days, and then present a plan with the necessary laws,” he said. Then it falls to the German parliament to decide upon each individual concrete step.

Whatever final plan is eventually adopted, Green party leader Annalena Baerbock, reminded, that “we’ll need more than what the compromise says if we want to meet [our 2030] climate targets.”

“The commission said energy customers should not face a surcharge for the phasing out of coal.” Whyever not? The principle means that the burden will be shifted from energy consumers to taxpayers at large, including those like the service sector who hardly use any. The lengths German politicians will go to to protect their favoured 19th-century industrial sector are amazing.