Plans for a new nuclear power plant in Czech Republic are currently on the brink of collapse. Jan Ondřich explains the remaining options.

The government is considering various options in favour of the realization of a new nuclear power plant (Public Domain)

The Czech government still remains hopeful that it can start construction of a new nuclear power plant. But the Czech utility CEZ, which is listed on Prague stock exchange and in which the government holds 70%, will not be able to build such a plant without some form of a state guarantee – the investment cost may easily reach a level of current market capitalization of the whole company, that is some USD 200 million.

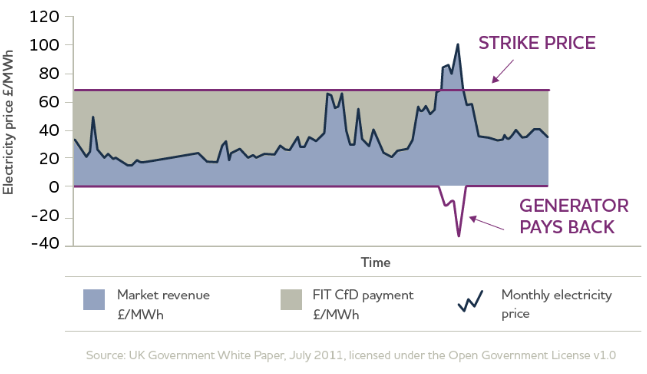

The government has considered various options, such as funding with the state budget, or the British-style contract for difference. This style of contract, which stipulates that the seller pays the buyer the difference between the value of an asset and the value at its contract time, means that when the market price for electricity generated by a CFD Generator (the reference price) is below the Strike Price set out in the contract, payments are made by the company (see diagram below).

The contract for difference guarantee has been rejected outright by Prime Minister Babis when he was heading the finance ministry in the last government. This has left the Czech government stuck between a rock and a hard place: the litigation risk from minority shareholders if the government ordered construction of the plant irrespective of its economic impact, and the threat that direct fiscal help can amount to illegal state aid under EU competition policy.

In the end the Czech government has only a few options if it wishes to go ahead and build the plant with recourse to the state balance sheet.

One option put forward by the Ministry of Industry and Trade is for the Czech state to set up a new special-purpose vehicle company of which it will own 100%. This company would acquire the new nuclear project from CEZ. In order to capitalize the company, the Czech state may sell a minority share to CEZ itself, to the EPC contractor or to other third-party investors.

This arrangement would enable the Czech state to raise its equity contribution by issuing bonds backed by the state budget. In addition, the Czech state could guarantee loans lent directly to the SPV by providing a parent-company guarantee – the lenders would have recourse directly against the state budget in case the SPV become insolvent. Such structure could enable the state to fund a new plant even without price floor mechanism if the lenders were comfortable enough with recourse to the state budget. However, it is unlikely that the state would find an equity investor for the minority share without guaranteed power price offtake since payback for the equity investor would solely depend on power price.

Another option proposed by the ministry draws inspiration from splitting of a German utility E.ON. In this scenario CEZ would be divided into two parts. Existing shareholders would be left with conventional power generation (a sort of Uniper), while the state would own carbon-free portfolio – that is renewables (mostly large hydro in the Czech Republic), grid and nuclear generation. The state-owned part of CEZ would then be capitalised through a state budget and would be able to borrow against a parent company guarantee provided by the government.

This scenario would also enable the construction of the new plant without power price guarantee if the Czech state was willing and able to provide enough equity for the construction and the lenders would be comfortable with the parent company guarantee. Just like in the first option, the government would find it difficult to attract co-investors without a firm guaranteed power price floor.

The “splitting” scenario presents one additional challenge – that is agreeing with minority shareholders on relative valuation of the two parts of CEZ. The state would end up owning the part of the company which has been generating the most shareholder value – the grid and the legacy nuclear assets. Minority shareholders would be left with largely lignite-fired generation fully exposed to the double risk of carbon and power prices. The cost of settling with minority shareholders would have to be included in the cost assessment of the new nuclear project.

It remains to be seen how the state can fund its new nuclear plant, and what the costs will be for taxpayers. In any case, it would be far cheaper to invest in renewable energy in the long run.

Other question:

Who would build it?

GE/Westinghouse is out,Hitachi is out and Mitsubishi is out.

EdF says they need at least some € 6 billion in subsidies/cash for free to build a merchant atom power plant.