In Europe, the transport sector accounts for a quarter of all greenhouse gases. A transformation of European mobility is therefore crucial for combating climate change.

Rail transport is the most climate-friendly mode of Transport (Public Domain)

Since the recent diesel scandal, it is clear that the transport sector is responsible for health-endangering air pollution. A European mobility shift must tackle several challenges simultaneously: our mobility must become more climate-friendly, air quality must be improved, and services such as travel times must be more attractive to Europe’s citizens.

The answer to these challenges is a closer European rail network for European passenger and freight transport. This concern is not new, but so far it has been sluggishly implemented at the European level. Too much of European rail transport is shaped by national interests.

Even in Germany, the political starting position for European rail transport is not favorable. With its own investment and tax policy, the Federal Government sends the wrong policy signals: rail transport pays the full VAT rate of 19 percent, while air traffic is completely exempt. Germany is thus in last place in the EU, ahead only of Greece and Croatia, when it comes to promoting rail travel. Germany also invests a much higher percentage of its public spending in roads than rail transport, unlike, for example, our southern neighbors Austria and Switzerland. In terms of climate and transport policy, this favoritism for road and air traffic makes no sense.

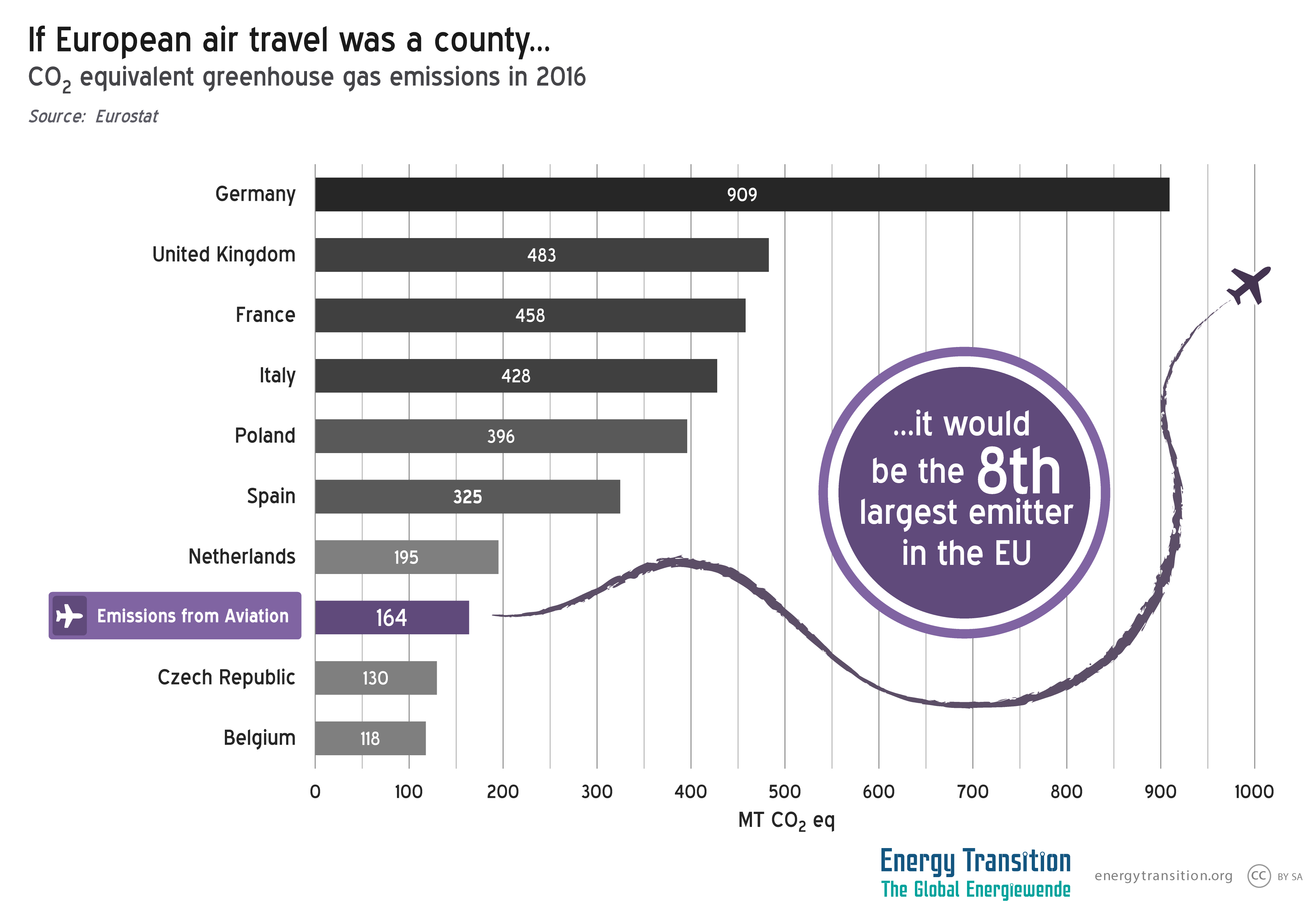

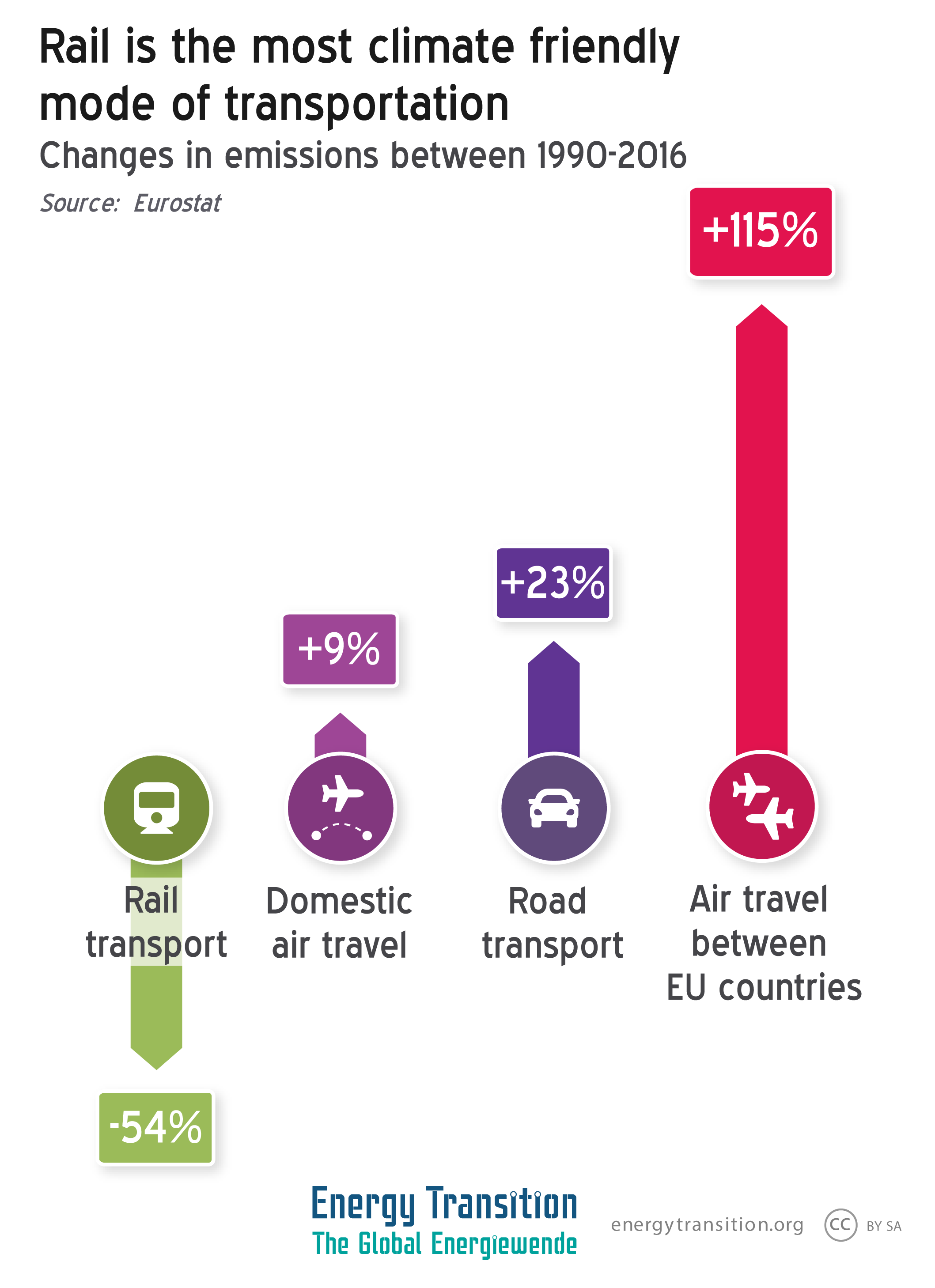

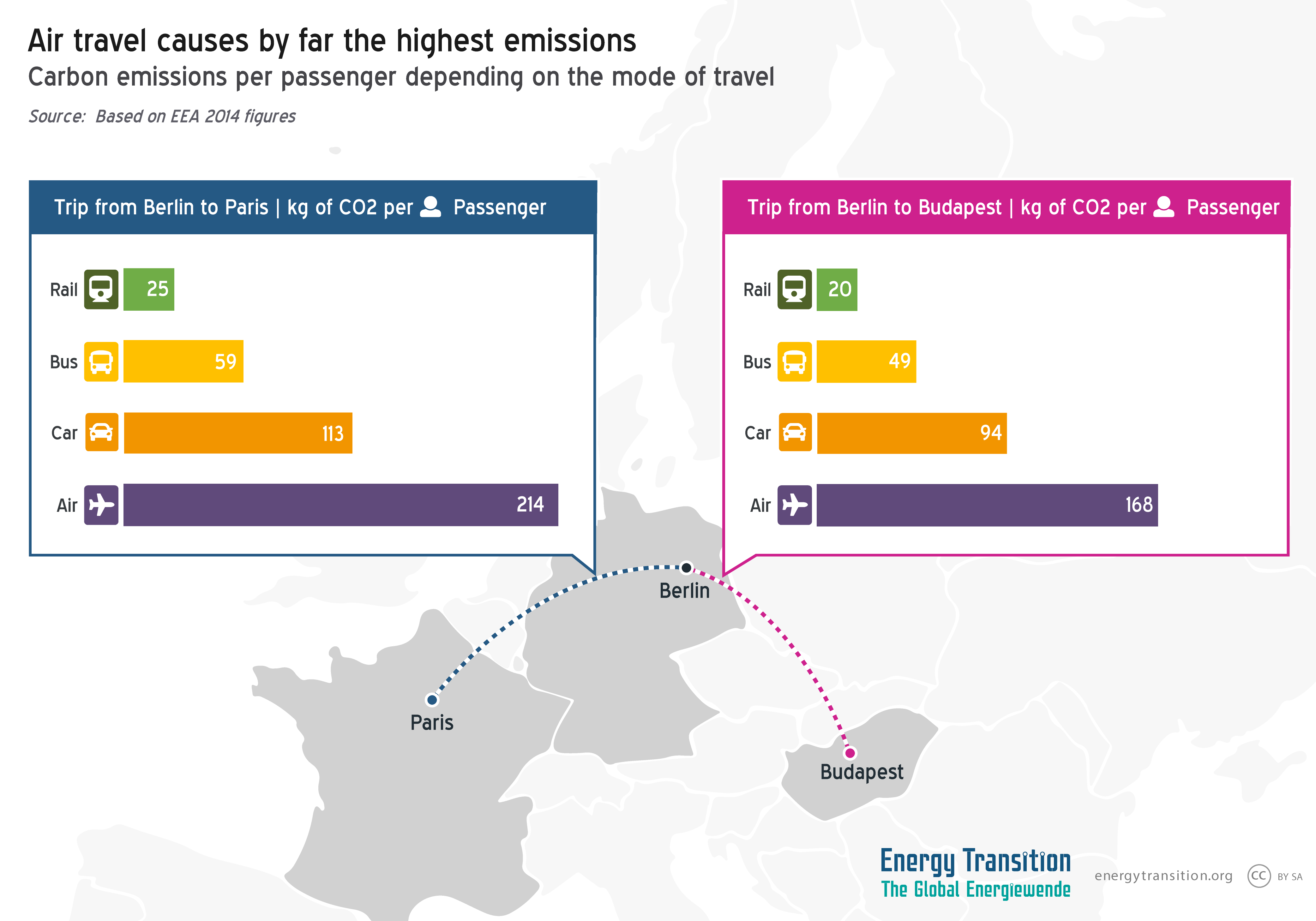

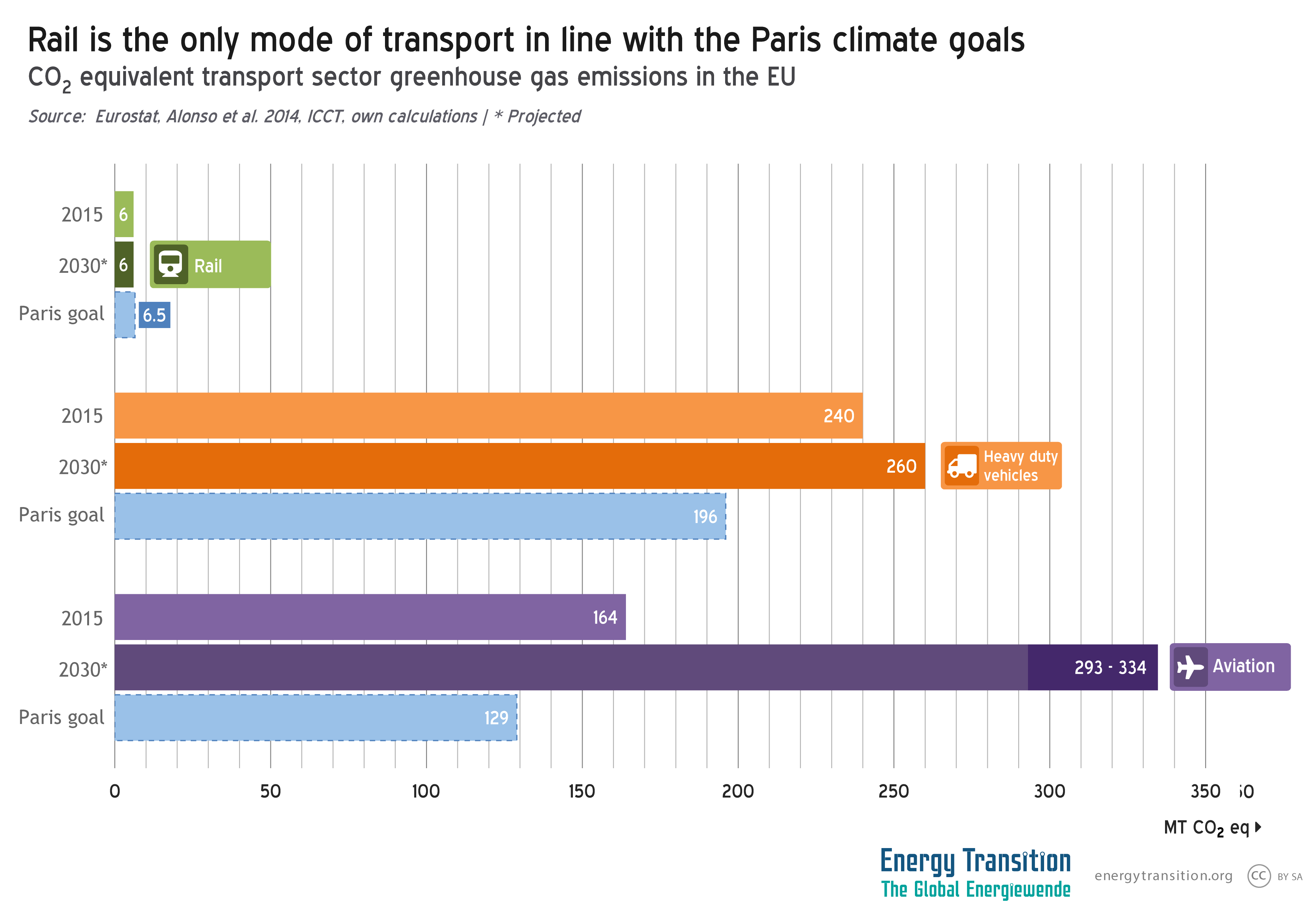

If Germany and Europe are serious about the Paris climate targets, the transportation equation must change. After all, rail transport is the most climate-friendly mode of transport compared with buses, cars and planes. In the Paris Climate Agreement, the European Union is committed to reducing greenhouse gases in the transport sector by 20 percent by 2030 compared to 2008, and by 60 percent by 2050 compared to 1990 levels. However, looking at the current situation and projections for the year 2030, rail transport is the only mode of transport within these objectives. In air traffic, the discrepancy is particularly dramatic. Here, the 2030 projection is almost three times as high as the Paris climate target. A stronger European rail network is therefore urgently needed in terms of climate policy. Unfortunately, the current progress on a European network is nowhere near where it needs to be.

If Germany and Europe are serious about the Paris climate targets, the transportation equation must change. After all, rail transport is the most climate-friendly mode of transport compared with buses, cars and planes. In the Paris Climate Agreement, the European Union is committed to reducing greenhouse gases in the transport sector by 20 percent by 2030 compared to 2008, and by 60 percent by 2050 compared to 1990 levels. However, looking at the current situation and projections for the year 2030, rail transport is the only mode of transport within these objectives. In air traffic, the discrepancy is particularly dramatic. Here, the 2030 projection is almost three times as high as the Paris climate target. A stronger European rail network is therefore urgently needed in terms of climate policy. Unfortunately, the current progress on a European network is nowhere near where it needs to be.

One reason for this is the general lack of prominent European support for the subject. In the EU Commission, it is not pursued by Directorates-General (DG) Transport, which is responsible for transport policy, but rather neglected by regional policy DG Regio. The liberalization of rail transport in Europe has not done much to improve the situation, and EU directives and regulations are being implemented sluggishly. Member states are reluctant to comply with the European Commission’s call for harmonization of standards in rail transport, such as signaling, security and power systems or other regulations.

One reason for this is the general lack of prominent European support for the subject. In the EU Commission, it is not pursued by Directorates-General (DG) Transport, which is responsible for transport policy, but rather neglected by regional policy DG Regio. The liberalization of rail transport in Europe has not done much to improve the situation, and EU directives and regulations are being implemented sluggishly. Member states are reluctant to comply with the European Commission’s call for harmonization of standards in rail transport, such as signaling, security and power systems or other regulations.

The lack of strict European implementation deadlines has also hampered implementation. National railway companies, which are predominantly state-owned in Europe, usually have little interest in providing their national rail network to foreign competitors. Time and again, foreign railway companies have to pay extra if they use the rail network of their European neighbors. Often the locomotives have to be changed at the borders so that the train can continue on the other side. This slows down intra-European rail transport unnecessarily and makes it unattractive to Europe’s citizens.

But there is another important reason for this slow harmonization process: the alleged lack of economic efficiency. At first glance, it is often not worthwhile for railway companies to engage in intra-European rail transport. Changing locomotives and a long wait at the border costs money. Yet if you look more closely, companies have pursued different strategies. The Deutsche Bahn from Germany abolished all night trains, mostly intra-European, at the end of 2016 , as they deemed it just a niche business. Yet other railway companies have taken over the European business for themselves and are making it profitable. The Austrian Federal Railways ÖBB is increasingly focusing on intra-European night trains, for example for the routes from Hamburg to Vienna or Zurich to Berlin. Since ÖBB serves a geographically smaller area than Germany, it engages in intra-European night train traffic, which already accounts for 20 percent of passenger traffic. The ÖBB has thus placed itself well in intra-European rail transport.

In order to further boost intra-European rail transport, infrastructure measures are urgently needed. Such measures could be used to close existing infrastructure gaps that have existed since the post-war period, for example between Colmar (France) and Freiburg. In addition, it is essential that these gaps are also prioritized, rather than only sponsoring major infrastructure projects. For the project Stuttgart 21 over 10 billion euros are spent to shorten the travel time only a few minutes; travel time between Berlin and Wroclaw could be cut by more than two hours for 100 million euros if the political course were set for a European rail infrastructure. Infrastructure investments in cross-border rail transport pay off directly in terms of connecting Europe and climate policy.

In order to further boost intra-European rail transport, infrastructure measures are urgently needed. Such measures could be used to close existing infrastructure gaps that have existed since the post-war period, for example between Colmar (France) and Freiburg. In addition, it is essential that these gaps are also prioritized, rather than only sponsoring major infrastructure projects. For the project Stuttgart 21 over 10 billion euros are spent to shorten the travel time only a few minutes; travel time between Berlin and Wroclaw could be cut by more than two hours for 100 million euros if the political course were set for a European rail infrastructure. Infrastructure investments in cross-border rail transport pay off directly in terms of connecting Europe and climate policy.

A better-connected Europe would also benefit Europe’s citizens. Not only would European border regions benefit economically, with positive effects on local jobs, but better transportation could also create a new space for European encounters. In a Europe, where national states are drifting farther apart, the cohesion of citizens would be strengthened. In the train, unlike in an airplane or bus, it is easier to talk to one’s immediate neighbor. One takes time for each other and experiences Europe from its human – not just bureaucratic – side.

A better-connected Europe would also benefit Europe’s citizens. Not only would European border regions benefit economically, with positive effects on local jobs, but better transportation could also create a new space for European encounters. In a Europe, where national states are drifting farther apart, the cohesion of citizens would be strengthened. In the train, unlike in an airplane or bus, it is easier to talk to one’s immediate neighbor. One takes time for each other and experiences Europe from its human – not just bureaucratic – side.

Therefore, intra-European rail transport should be understood as an integral element of European transport, climate, investment and structural policy. European policy must finally pave the way for the harmonization process to be stimulated, the Member States to adhere to fixed deadlines, and intra-European train services to be attractive to Europe’s citizens. Of course, this also means that tax, market and subsidy mechanisms allow European train journeys to compete at a competitive price with aviation. Only then can rail transport bring out its full potential in European climate policy.

This is something that should happen, but as you note, the issue is politics.