Developing countries have contributed the least to climate change, yet they are the most vulnerable to climate catastrophes. Now rich countries are championing the “solution” to climate catastrophes in the form of premiums for insurance schemes. Liane Schalatek and Julie-Anne Richards explain why insurance hasn’t worked in Dominica and Malawi.

Despite insurance, the costs for climate catastrophes fall mostly on citizens of vulnerable countries (Photo by Arie Kievit NLRC, CC BY-NC 2.0)

A new report from the Heinrich Böll Foundation North America highlights that developed countries advocate insurance as the main response to climate disasters to distract from their moral and legal responsibility to pay for the environmental damage they have caused.

It’s an egregious injustice: vulnerable countries are paying the majority of direct costs of climate disasters, and are also being forced to pay for the “solution” of insurance for climate catastrophes.

The report examines three case studies in detail: Dominica, the US, and Malawi.

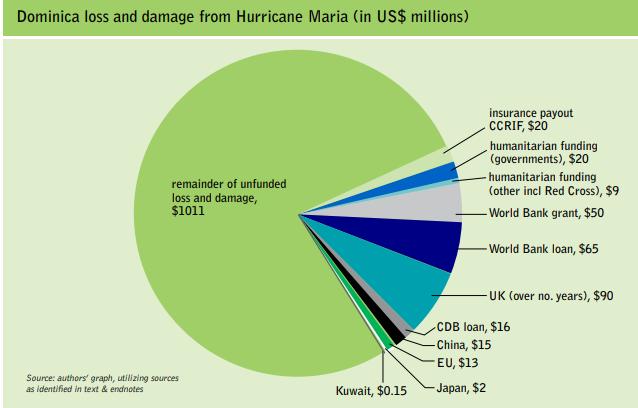

Hurricane Maria is now regarded the worst natural disaster on record to affect Dominica and Puerto Rico and was the deadliest Atlantic hurricane since 2004. The catastrophic loss and damage as a result of Hurricane Maria in Dominica has been estimated at US$1.37 billion (or 226 percent of Dominica’s GDP).

Sovereign insurance under the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF) provided just US$19.3 million or 1.5 percent of the cost of loss and damage incurred. While CCRIF funding had the advantage of arriving quickly, it was vastly overshadowed by traditional international assistance provided by other governments.

Source: Julie-Anne Richards and Liane Schalatek “Not a silver bullet”

The vast majority of the costs for the loss and damage and recovery will be paid for by the people of Dominica. There is no way to scale up insurance to deal with loss and damage of this size – the premiums would be prohibitive.

In comparison, the impact of Hurricane Harvey on Texas was largely covered by the government. Interestingly, the United States is one of the most heavily insured countries on earth, yet as damage from climate-related events increases, paying for loss and damage is being shifted from the private to the public sector: the exposure of the US federal government grew more than four times the rate of private sector insurance exposure. It is the public sector that is coming to the rescue of Americans in the face of climate extremes. The US and other developed countries should acknowledge that the same will be necessary for developing countries.

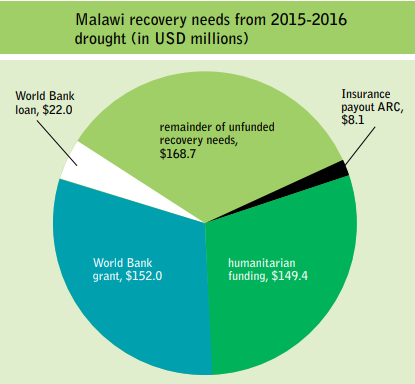

The study also analyses the experience of Malawi with sovereign-level drought insurance from the African Risk Capacity (ARC). ARC served as Malawi’s primary source of risk financing to address the devastating impacts from extreme weather events. In 2015, Malawi faced both a once-in-500-years flood and then an extended drought, causing US$365.9 million in loss and damage.

Source: Julie-Anne Richards and Liane Schalatek “Not a silver bullet”

ARC initially challenged that an insurance claim payout had been triggered, but ultimately paid out US$8.1 million nine months after Malawi declared an emergency. But this was not only too little too late, it also undermined the chief advantage of climate insurance—an immediate payout to address urgent needs post-disaster.

Even a doubling or tripling of insurance coverage for poor countries would have only scratched the surface of the loss and damage associated with the major climate events analyzed. In fact, insurance cannot be scaled up to the point where it would provide a viable disaster response. In each case, the bulk of support came from other sources of public finance.

In the future, developing countries will have to rely on international finance. Selling disaster insurance as a panacea, when it is at best only capable of playing a small supporting role, is not helpful.

The report shows that there is little evidence that climate insurance is a cost-effective approach. Rather, evidence shows that other options – providing governments with public funds to build up social safety nets, alternative livelihood programs, relocation funds, national contingency funds, and concessional credit – are a better solution.

However, there are ways for climate insurance to work. For example, a global solidarity fund could be established through new and innovative, polluter-pays sources of finance. A Climate Damages Tax (on fossil fuel extraction) could be implemented equitably, and generate a significant portion of the $300 billion which will be needed by 2030 due to climate disaster losses and damages.

Liane Schalatek and Julie-Anne Richards are the authors of the report Not a silver bullet: Why the focus on insurance to address loss and damage is a distraction from real solutions.