Last year, 330,000 households in Germany had their power cut off because bills had not been paid. Ideally, the number would be zero. But is the number high in comparison to other countries? Craig Morris investigates.

Which Germans be able to heat their homes this winter? (Photo via Wikipedia, edited, CC BY-SA 4.0)

If you recently read headlines like “Germany set to pay customers for electricity usage as renewable energy generation creates huge power surplus” or “Germans Could Be Paid to Use Electricity This Weekend” (Bloomberg) and wonder how that can happen in the country with the second highest power rates in Europe, you’ve come to the right place.

But first, this: In October, Germany’s Network Agency – the regulator of the power grid, gas networks, and telecommunications – shared a draft of its Monitoring Report for last year. A lot is in the report given the Agency’s broad mandate (here’s the 422-page PDF from 2016). But the press always picks up one thing: the number of households that had their power cut off because they couldn’t pay. Note that this number is not in the 2016 report’s Key Findings, which cover three full pages. It obviously isn’t considered a key finding.

In 2016, the number was 330,000, down insignificantly from 331,000 in the previous year. The high was 350,000 in 2014. Households had to be in arrears for at least 100 euros, and multiple reminders need to be issued along with a final warning for power to be cut off. The fee for turning the power back on averages 35-40 euros. Households that repeatedly fail to pay can have prepaid meters installed; some 20,000 were added in 2015.

How long were these people without power on average? The report doesn’t say. Apparently, such data are not collected. And that’s just the beginning.

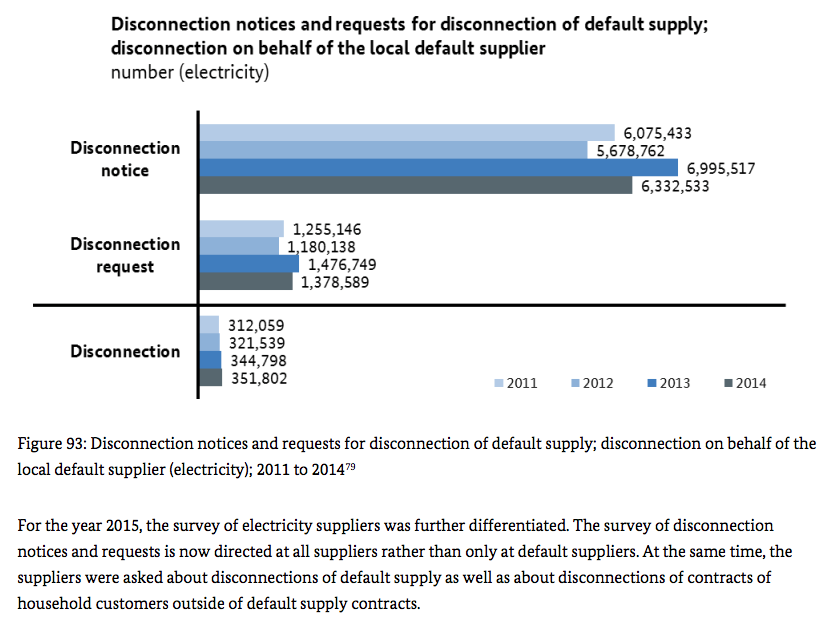

In the screenshot above from the 2016 report, note first the mention of “default suppliers”; we’ll come back to that below. But first, six million “notices” were sent out. And while the number rose from 2011-2014, it has dropped since. But still, how many is that?

Germany has some 44 million households, so 14% of them were behind payment on power bills in 2014 (above). But comparisons with other countries are hard. First, current data are not available everywhere; one reason everyone reports on the German situation is because the data allow us to. An OECD report from May (PDF) used stats mostly from 2010. And it lists five different ways that countries measure the impact of energy expenses on poor households.

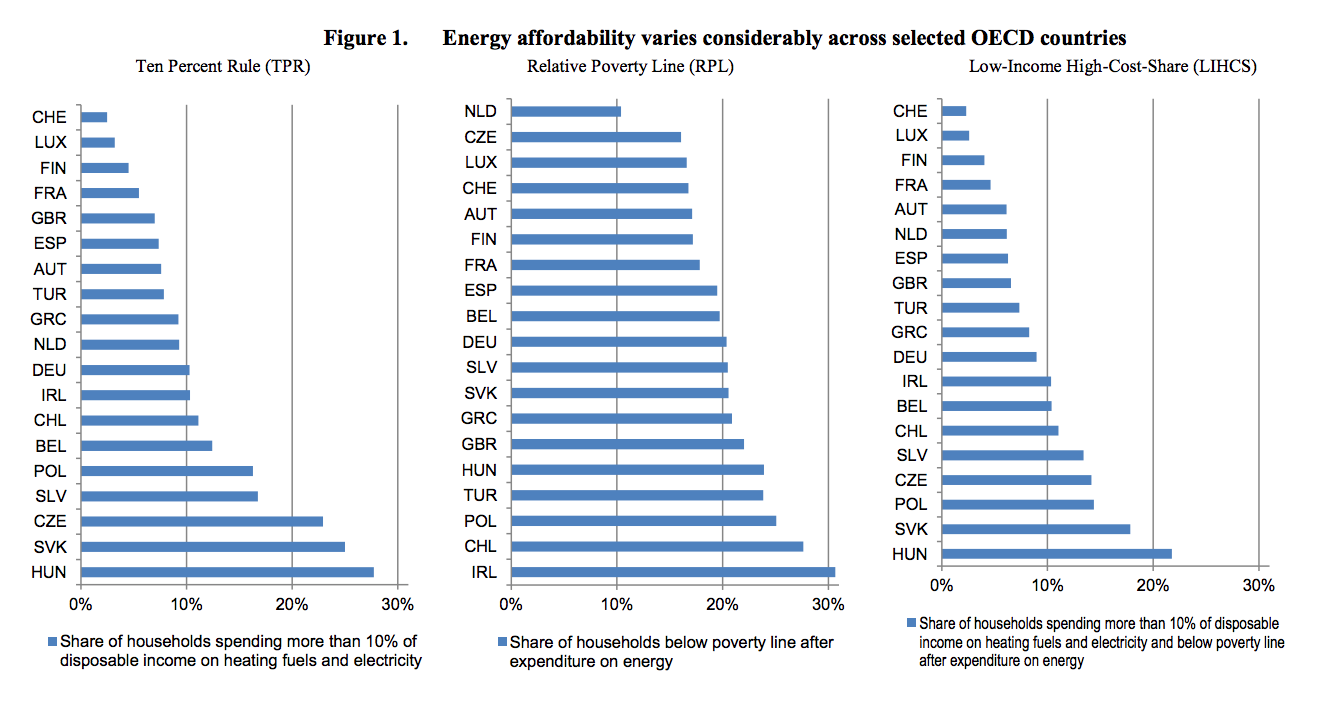

The UK, for instance, speaks of “energy poverty” when a household spends more than 10% of its income on energy. Germany doesn’t use such a metric at all officially, but other data collected allow the comparison to be made. But the metric chosen is crucial: “the United Kingdom has the fifth lowest share according to the ten percent indicator, but the sixth highest according to the relative poverty line indicator,” the OECD report explains.

Source: OECD

In all three of the cases, Germany lands smack-dab in the middle. The problem is, we are talking about energy for power and heat (specifically, electricity, heating oil, and natural gas, with the latter also being used for cooking) here, not just electricity. In other words, this a mess.

Note as well that the United States, though an OECD member, is not included in the study. It wouldn’t be possible; the country doesn’t collect proper statistics for a comparison.

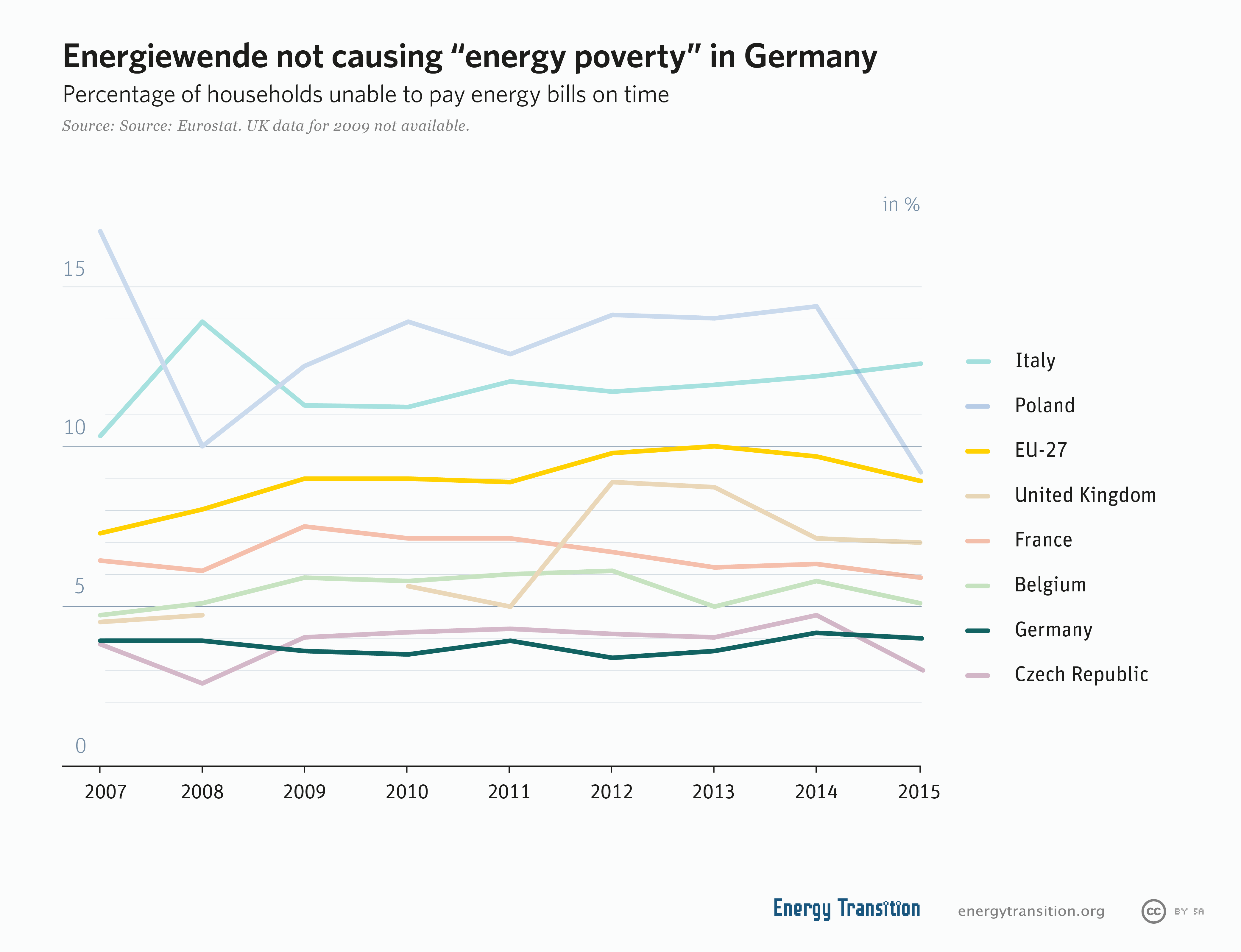

We do know from EU data (up to 2015) that Germany performs quite well in terms of the number of households behind on “energy bills” (heat and power). There are two reasons: 1) Germany is relatively rich, and 2) German welfare covers heating bills. But German welfare doesn’t cover power bills, so they are a challenge for poor families in Germany.

One other thing complicates the matter: as the Network Agency’s Monitoring Report explains, you get a bad credit rating when you default on bills, so switching to a cheaper provider become harder. As a result, poor households get stuck with the “default supplier” (the former local monopoly utility), which is generally more expensive. One easy fix is to cover power bills (maybe up to a certain extent) under welfare – and also allow people to choose providers regardless of their credit rating.

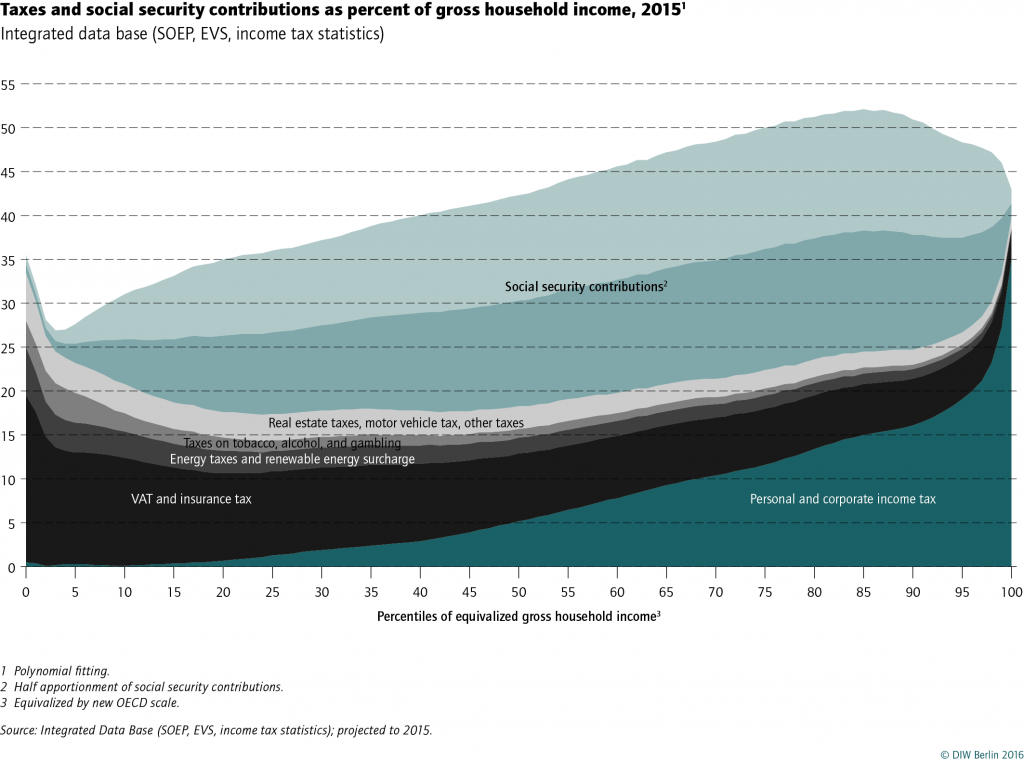

Otherwise, keep in mind that energy prices are not energy bills and that VAT is the main tax type that regressively affects the poor the most, as the “whale in a bathtub” below shows. In the end, the best way to fight “energy poverty” is to fight poverty.

Source: DIW

Now back to those headlines: basically, spot market prices were negative. But households buy retail power, and those rates are the second highest in Europe. They’ve been among the highest for the past two decades, so the Germans use power efficiently – hence, their power bills aren’t that high.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

[…] Morris von energytransition.org geht ist diesen Fragen in dem sehr lewenswerten Beitrag Is 330,00 (sic!) German households without power a lot? nachgegangen. Er zeigt an Hand der Daten auf, dass Deutschland im OECD-Vergleich im Mittelfeld […]

As if it wasn’t enough to lose their power, these people how to deal with elitists telling them it doesn’t matter.