Electric vehicles (EVs) are approaching a tipping point, as a wave of new cars are matching the cost and performance of traditional petrol cars. Three breakthrough electric cars, from GM, Tesla, and Nissan, are offering drivers everything they want – but without the pollution. Ben Paulos takes an in-depth look.

Tesla Model 3 has one of the best ranges of the new electric vehicles sold (Photo by Steve Jurvetson, edited, CC BY 2.0)

Growth of electric vehicles is being driven by the confluence of falling prices and improved performance of batteries, consumer demand, and especially regulatory demand.

The new cars

GM’s Chevy Bolt, Tesla’s Model 3, and Nissan’s LEAF 2.0 are average priced cars with 250 mile ranges. While previous electric cars had either the range (Tesla) or the price (Nissan), the new cars have both. This is the breakthrough that many have been waiting for, triggering a round of new policies, new product announcements from major car companies, and new forecasts of future sales.

The Chevy Bolt was the first on the streets, boasting an EPA-estimated range of 238 miles (383 km). With a sticker price of $36,620, it has been a steady seller, trailing only the Tesla Model S in the most recent sales quarter, according to EV Obsession.

The Tesla Model 3 went into production in July, with the goal of producing 5000 cars per week by year’s end. But Tesla has struggled with “production bottlenecks,” according to CEO Elon Musk, and appears unlikely to reach that goal.

Musk whipped up a frenzy around the Model 3 by collecting reservation deposits of $1000 each from half a million potential customers, eager to buy some of the Tesla mystique for only $35,000. As a result, Tesla got an interest free loan of $616 million from its customers, mostly from Model 3 deposits.

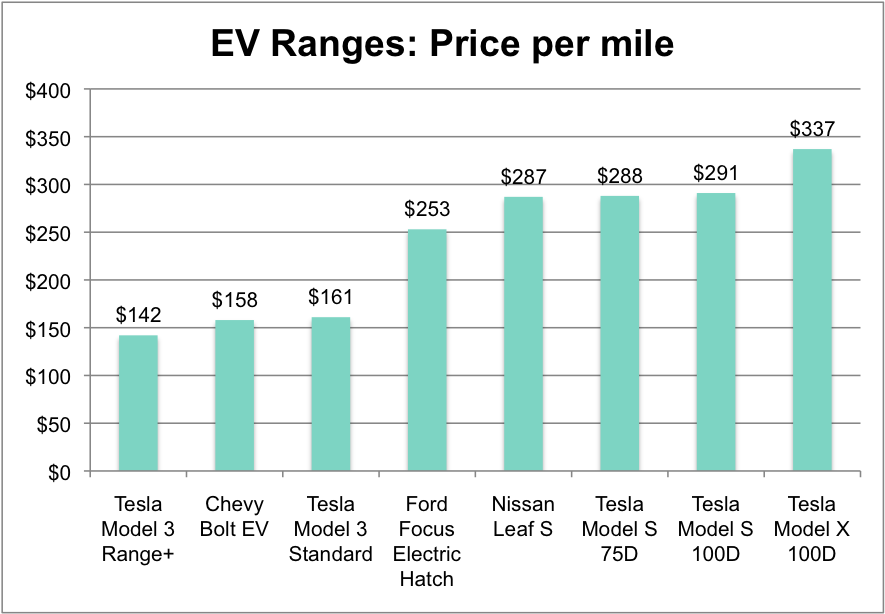

The $35,000 base model has a range of 220 miles while the $44,000 “long range” version can go 310 miles, giving it the most miles-per-dollar of any battery-electric car on the market, according to Bloomberg.

The new Nissan LEAF hit the market this October in Japan, and is expected in the US early next year. While the initial version of the LEAF has been a top seller, the new 2018 model will have an improved range of 150 miles, as well as a host of “smart” features, like following the car ahead at a preset distance, staying centered in a lane, and pedestrian detection. The sticker price starts at only $29,990. Nissan has said that the 2019 version will have a larger battery pack and a range well over 200 miles.

Big policy changes

This breakthrough on price and performance has inspired policy makers around the world to become more aggressive about electric vehicles.

Norway, England, France, Scotland, India, and the Netherlands have all announced plans to phase out internal combustion engines.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel has yet to commit to a phase-out of diesel cars, but has acknowledged the British and French plans “were the right approach,” according to Reuters.

“We need to organize a smooth transition into the new era so that people keep their jobs,” she said, during the recent campaign season.

The biggest potential impact is from China, by far the largest single market for new car sales. In 2017 so far, total Chinese vehicle sales have risen 4.3% to 17.51 million units, while US auto sales have fallen 2.7% to 11.35 million vehicle units, according to industry data tracker Market Realist.

In September, the Chinese government announced that they too are “researching” a phase-out of internal combustion cars. China currently has a goal of 20% of all car sales to be from EVs and plug-in hybrids by 2025.

Norway is currently the world leader in EV adoption per capita, thanks to substantial incentives, like an exemption from the 25% tax applied to vehicle sales. Norwegian buyers set a new record in June, with 42% of new cars being EVs, including 27% from battery-only cars.

Regulatory demand for EVs initially came from California, where the Air Resources Board (CARB) imposed a zero-emission / low-emission vehicle mandate in 1990, known as ZEV-LEV. The rule required that in 2% of vehicles sold in California had to be ZEVs by 1998, increasing to 5% in 2001 and 10% in 2003. Subsequent changes allowed a range of other technologies to earn credits, including hybrid cars.

Auto-makers challenged the rule in court, but grudgingly complied, with GM releasing the EV1 in 1998, a battery-only EV model with a range of 124 miles. But the price of electric vehicles was high, demand was low, and car makers had more success with hybrid cars.

Regulators at CARB saw the success of hybrids as a way to drive bigger air quality gains more rapidly. Instead of a small number of zero-emission cars, they could put a large number of low-emission vehicles on the road.

While critics castigated CARB chair Alan Lloyd as the man “who killed the electric car,” CARB’s revision of the rules in 2001 launched the global hybrid industry.

Toyota especially jumped at the hybrid opportunity in California with the Prius, selling over 800,000 units over the first ten years in the US; about a quarter of all Prius’ were sold in California.

Nine states followed California’s lead in adopting ZEV-LEV laws, mostly in the Northeast and Northwest. This move created essentially two car markets in the US – “California” cars and non-California cars.

Altogether, the “California car” states require that 15% of new vehicle sales be ZEVs by 2025, or about 4 million vehicles. California still dominates sales, with over half of all plug-in vehicles sold nationwide in 2017 to date, according to the Association of Global Automakers. Almost 5% of new sales in California were plug-ins, compared to only 1.1% nationally.

Policies trigger big plans

The combination of market and regulatory pressure is now pushing car makers to move into EVs in a big way.

Volvo was the first major car company to announce plans to phase out conventional engines, committing to selling only hybrid and electric cars by 2019. GM recently announced that it will sell at least 20 new all-electric and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles globally by 2023. Ford too said it would add 13 electric models over the next several years, with a five-year investment of $4.5 billion.

Altogether, Bloomberg New Energy Finance expects over 120 different models of EV to be on the market by 2020, including SUVs and small vans. The “EV Revolution” is underway, they say, with EVs accounting for 54% of new car sales by 2040.

“Tumbling battery prices mean that EVs will have lower lifetime costs, and will be cheaper to buy, than internal combustion engine (ICE) cars in most countries by 2025-29.”

The International Energy Agency, typically more conservative, predicts there could be between 40 million and 70 million electric cars on the roads by 2025. The ten member countries of IEA’s EV Initiative recently launched the EV30@30 campaign, setting a collective goal of a 30% market share for electric vehicles by 2030.

While the EV revolution currently seems inevitable, the coming year will be critical in the success of clean cars. Sales of the three breakthrough models from Chevy, Tesla, and Nissan will dictate whether the public is willing to follow the regulators.

Bentham Paulos is an energy consultant and writer based in California. His views are his own, and don’t necessarily represent those of any of his clients. For more information see PaulosAnalysis.com.

The normal English plural of Prius is surely Priuses (omnibus : omnibuses). If you want to show off your Latin, go for Prii (Horatius : Horatii). If you want to show it off even more, use Priūs {manus : manūs).

The growth of EVs does not depend on Tesla, Nissan, and GM. It depends on China. A single Chinese car leasing company, Panda, has signed a MOU for 150,000 EVs. That’s not a misprint.

[…] has been promoting low emission vehicles since the 1990s, and has a goal of putting 1.5 million electric vehicles on the road by 2025. It is currently home to 330,000 plug-in electric vehicles, accounting […]