The Ruhr region of Germany was once a mining stronghold; now residents are seeking new livelihoods. The last hard coal plants in Germany will close in 2018, but what happens to their communities when they do? Emma Bryce looks at a just transition.

The former Zollverein coal mine in Essen, Germany, was closed more than three decades ago, but instead of being left in the dust, it was repurposed into a museum and tourist attraction. In 2001, the former mine became a UNESCO world heritage site and now welcomes more than a million visitors each year. (Photo by Thomas Wolf, edited, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

Seventy-seven-year-old Heinz Spahn, whose blue eyes are both twinkling and stern, vividly recalls his mining days. Zollverein, the mine where he worked in Essen, Germany, was so clogged with coal dust, he remembers, that people would stir up a black cloud whenever they moved. “It was no pony farm,” he says, using the sardonic German phrase to describe the harsh conditions. The noise was at a constant 110 decibels, and the men were nicknamed waschbar, or raccoons, for the black smudges that permanently adorned their faces.

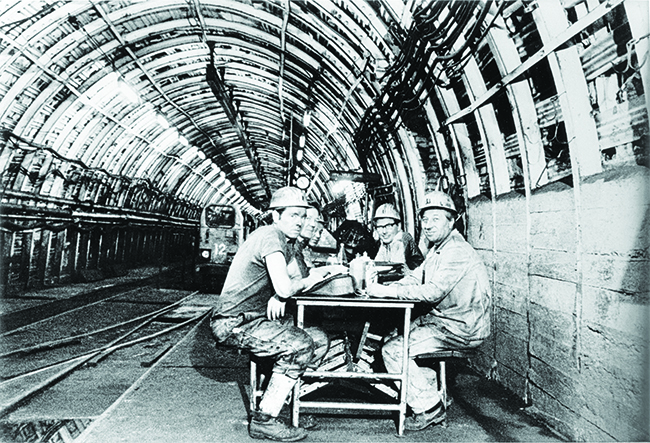

Zollverein miners are seen in the 1970s during a break. At their peak, the mines in the Ruhr valley employed about 600,000 workers, entwining the region’s identity with coal. But in the 1970s, coal imports from other countries drove up the price of German production and it became unsustainable for the government to keep subsidizing the mines. This began the phaseout of coal. (Photo © Fotoarchiv Ruhr Museum)

Heinz Spahn, (left) who worked at Zollverein until the mine shut down on December 23, 1986, remembers when the air there was clogged with coal dust. Now the air is clean, and Spahn teaches visitors about Zollverein’s history.

The Ruhr has become an attractive place for businesses to invest, says Frank Switala (right), a local tour guide who works at Zollverein. But the coal mine has left its mark; after centuries of tunneling below ground, Switala said the earth below the Ruhr valley is like “Swiss cheese” and sinkholes are a regular occurrence. (Photos by Emma Bryce)

Today, the scene inside Zollverein is very different. The air is clean, and its 8,000 miners have been replaced by 1.5 million tourists annually. It’s now a world heritage site of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, and Spahn, who worked here until the mine shut down on December 23, 1986, is employed as a guide to teach tourists about its history. “I know this building in and out. I know every screw,” he says fondly. Zollverein is also the primary symbol of Germany’s transition away from fossil fuels toward renewable energy, a program called the Energiewende that aims to generate 80 percent of the country’s energy from renewables by 2050. That program has transformed Germany into the global poster child for green energy. But in the Ruhr region—the former industrial coal belt—do people welcome the change?

Spanning roughly 1,700 square miles, the Ruhr valley lies in the state of North-Rhine Westphalia, made up of a matrix of 53 cities that sprang up around coal mines in the 1800s. At their height in the 1950s the mines employed about 600,000 workers, entwining the region’s identity with coal. “Coal runs through my whole life,” says Spahn, whose grandfather, father, and two sons were miners too. But in the 1970s, as coal imports from other countries drove up the price of German production, it became unsustainable for the government to keep subsidizing the mines. And so the phaseout of coal began.

The Transition Away From Coal

Today, just two hard-coal mines remain, and in 2018 they’ll both be shut down. Germany still extracts soft brown coal called lignite at hundreds of opencast mines across the country, but with the German federal election, the new government will likely turn its attention to this type of coal and will set a deadline for its phaseout too. That will dock another several thousand jobs in the Ruhr alone, forcing the government to consider how to achieve a fair and final phaseout and the role of renewable energy in that.

The transition away from hard coal has left a lingering legacy in some cities, where unemployment can exceed 10 percent. But despite the heavy historical personal toll, for hard coal, overall “it was really a soft and just transition,” says Stefanie Groll, head of environmental policy and sustainability at the Heinrich Boll Foundation in Berlin. “In the Ruhr area, union representatives and local politicians worked out a plan to compensate and requalify people who worked in the coal industry.”

For families like Spahn’s, it was a success: the mines where his sons worked launched a proactive campaign in 1994 to train employees for different careers. “My one son is now a professional security guard and the other is a landscaper,” he says.

At Zollverein, the viewing platform offers a 360-degree view on the landscape-level change the transformation has brought about. The Ruhr’s low-built cities are set among lush forests and parks. Amid smokestacks stand the spires of wind turbines. Zollverein’s 55-meter-high mine shaft itself makes a striking contribution to the landscape. In 2000, Germany’s former President Johannes Rau dubbed it “the Eiffel Tower of the Ruhr”—and in doing so highlighted an important trend: the cultural rebranding of the Ruhr’s industrial history.

The swimming pool at Zollverein was created in 2001 as part of the art project “Contemporary Art and Criticism” by Frankfurt-based artists Dirk Paschke and Daniel Milohnic. The pool now is a popular meeting point for children and young people in Essen, Germany. People 30 years ago would have scoffed at the thought of holidaying here, says Frank Switala, a local tour guide who works at Zollverein. (Photo © Jochen Tack/Stiftung Zollverein)

People 30 years ago would have scoffed at the thought of holidaying here, says Frank Switala, a local tour guide who works at Zollverein. “Now the number of hotels has increased. There are new museums. We have five philharmonic orchestras in the Ruhr area, and so many theaters.” The mines themselves have become a cultural stage: a museum and gallery at Zollverein alone attracts 250,000 visitors a year, and several mines now host music concerts and food and cultural festivals. In the nearby city of Bochum, an old industrial plant, now the site of the German Mining Museum, is set somewhat incongruously in an inner-city suburb. But its cultural presence appears to have boosted, not undermined, the area’s status: the surrounding homes are stately, flanked by lush gardens. The change hasn’t gone unnoticed, for the Ruhr was officially named Europe’s cultural capital in 2010.

Zollverein, like many former mines, is now also home to companies and creatives. Artists, jewelry designers, choreographers, design firms, and tourism companies are just a sampling of those who have made the trendy industrial space their home. The Ruhr has become an attractive place for businesses to invest, says Switala. And yet moving away from coal hasn’t just been about economic revival. “The earth beneath this region is like Swiss cheese,” he says. Riddled with tunnels from centuries of mining, the geography has become so brittle that the region regularly battles with sinkholes. Groundwater flooding the old tunnels now has to be laboriously pumped out.

The mines’ legacy of pollution also became untenable. “Every evening my grandmother tested the wind and then decided whether or not to leave the washing out,” Switala recalls. Otherwise, her clothes would be black in the morning. Knowing the health risks, his grandfather who had worked in the mines all his life adamantly kept his five children out, Switala says. “That was quite common in that generation. You wanted your kids to have a better life than you did.”

The Transformation of the Mines

Roland Sauskat, a social worker with a local soccer club called Rot-Weiss-Essen, shares a similar family story. In the neighborhood of Gelsenkirchen-Horst, he walks around the grounds of Nordstern, the former mine—now museum, events space, and business park—where his father and grandfather spent their working lives. His grandfather started mining when he was just 14, at a time when they still used horses underground to haul coal. He died of the schwartze lunge—black lung—a disease triggered by the accumulation of small rock particles inhaled during mining, which ultimately causes tissue death in the lung. His father died of lung cancer. Despite this, Sauskat doesn’t recall his family expressing any bitterness about the work. “It was a job,” he says bluntly. Ironically, Sauskat himself was spared this fate because of childhood asthma, which made him unfit for the mines, a problem he says was common among the region’s youth. In any case, his family wouldn’t have wanted him to work in the mines. “Every worker here said my son will do better with his life,” he notes, as we ascend Nordstern’s mine shaft. At the top of Nordstern’s mine shaft, an imposing, 18-meter-high statue called Hercules stands as a symbolic tribute to the miners: erected there by a German artist in 2010, he gazes over the Ruhr, observing the regional transformation as if he’s curating it.

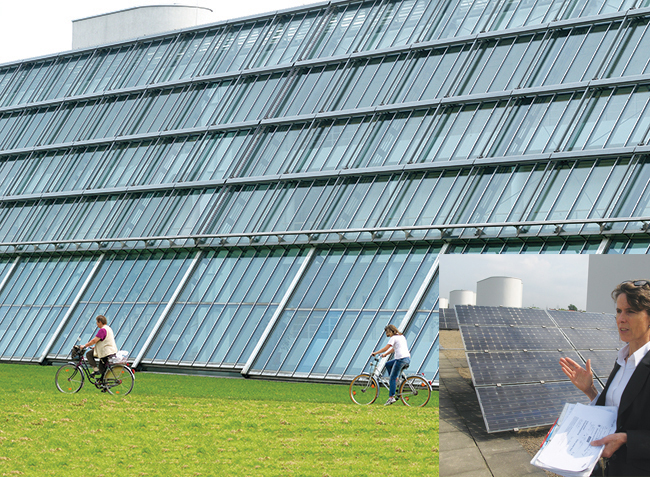

The Science Park in Gelsenkirchen, Germany, was built on the site of a former coal-powered steel plant. The building’s glass facade looks over a man-made lake flanked by rolling lawns, and its roof is outfitted with 900 solar panels that generate a third of the building’s electricity. Hildegard Boisserée-Frühbuss (inset), project manager of the park, says the building houses 55 businesses mostly focused on science, technology, and renewable energy development. (Photo by Unkel/ullstein bild/Getty Images, and inset photo of Boisserée-Frühbuss by Emma Bryce)

Six miles south, near Essen—one of the region’s largest and most prosperous cities, whose center was once home to more than 20 mines—Sauskat points out signs of environmental change that the transition has ushered in. In the district of Altendorf, a former coal and steel production site is now a lake at which people walk their dogs and have picnics, he says. It’s part of the wider Emscher Park initiative, a multimillion-euro project to restore, create, and connect green spaces along a 300-square-mile span of the Ruhr that was once devastated by mining.

The cities show signs of other, more pragmatic economic changes too. In Gelsenkirchen, locals experience some of the highest unemployment rates, hovering around 15 percent. Its quiet streets betray signs of economic struggle, with many businesses boarded up. But since the early 2000s, it has been trying to revisit its former industrial prosperity with the Science Park, a hub for regional business, which lies on the site of a former coal-powered steel plant. The building’s glass facade looks over a man-made lake flanked by rolling lawns, and its roof is outfitted with 900 solar panels that generate a third of the building’s electricity. “Gelsenkirchen was called the city of a thousand fires. It became the city of a thousand suns,” a nod to the park’s huge solar roof, says Hildegard Boisserée-Frühbuss, project manager at the park. The building now houses 55 businesses mostly focused on science, technology, and renewable energy development. Boisserée-Frühbuss spends her time working with local colleges and schools to give the youth exposure to these fields, in the hopes that they’ll be inspired to find employment there. “Once it was a steel foundry. Now the Science Park is a thinking factory,” she says.

Questions of Employment

With the move toward renewables, how much the Ruhr will benefit—having sacrificed so much toward this clean energy goal—has become a primary focus. There are 330,000 people employed in the renewable sector in Germany; 45,000 of those are in North-Rhine Westphalia, and that number will grow, predicts Jan Dobertin of the National Association of Renewable Energies, in North-Rhine Westphalia (LEE NRW). “The Ruhr region is now one of the biggest providers of green economy—such as efficiency technologies, recycling, or renewable energy,” Dobertin says. LEE NRW works with regional energy companies to build better political frameworks for integrating renewables in the Ruhr. “Our argument is that the renewable energy sector is much more employee intensive” than fossil fuels, Dobertin says. A recent poll of Ruhr residents, carried out by LEE NRW, suggests that it has the public on its side: 64 percent of those polled want renewables to be a priority for the state government of North-Rhine Westphalia.

The coal-fired power station fed by the mine Prosper-Haniel spews emissions into the air on February 6, 2007, in Bottrop, Germany. Prosper-Haniel, one of the two last hard-coal mines in Germany, is scheduled to close in 2018. Ahead of that closure, a consortium of local universities, consultants, and mining operators is exploring the chance to turn the plant’s deep mine shaft into a hydroelectric storage facility. (Photo by Ralph Orlowski/Getty Images)

In keeping with this trend, just outside the small city of Bottrop, a plant called Prosper-Haniel, one of the two last hard-coal mines in Germany, has become the front line of a renewables experiment. Ahead of its closure in 2018, a consortium of local universities, consultants, and mining operators is exploring the chance to turn the plant’s deep mine shaft into a hydroelectric storage facility. The plan is at a preliminary, exploratory stage, cautions Andre Niemann from the University of Essen-Duisburg, who is leading the research team. But if it works, it could store and provide power for over 400,000 local homes. He’s motivated by the chance to revive the industrial landscape he grew up in. “The question will be, what did we do to give the region back to the people?” he says.

What the project can’t change is the fate of the 2,600 employees at Prosper-Haniel who will lose their jobs next year. If the hydroelectric project goes through, it won’t be a major employer, Niemann says. This concern extends to lignite mining, which is predicted to go by 2040, officially closing the era of coal. “There’s no officially approved ‘just transition plan’ for the three remaining lignite regions in Germany,” cautions Groll. That will hopefully be mapped out when lignite’s future is decided, which some see as an opportunity to correct some of the wrongs that were committed during the transition from hard coal, like the legacy of unemployment in some cities. “We don’t want to repeat its mistakes,” Dobertin says. He’s adamant about the potential of renewables to improve the Ruhr’s fate, though he understands that this threatens its identity, especially for its older generation. And he does ponder how his grandfather, the last miner in his family, would have felt about his anticoal stance. “But I think ultimately my grandfather would have been happy about it, because we have to do something about climate change, and renewables are one big solution for this challenge.”

Reflecting on this future, Heinz Spahn, sitting just meters away from the machine where he toiled for 26 years, shares his views. “Eventually the [coal] legacy will die out, and that makes me sad. But I have made my peace with it,” he says. “I am very happy that the Ruhr region has become so green and healthy. I am glad the youth today will have a better childhood than I did.”

This article was originally published by the Stanley Foundation.

Emma Bryce is a London-based freelance journalist who writes about science and the environment for the Guardian, Wired UK, Audubon, Anthropocene, and others. She reported from Marrakech, Morocco, on the 2016 climate talks as part of an International Reporting Project fellowship, organized in collaboration with the Stanley Foundation.