French President Macron has proposed closer cooperation with Germany to strengthen the EU. One aspect is higher carbon prices – between 25 and 30 euros per ton of CO2. Craig Morris explains what impact different prices would have on Germany’s energy system.

Germany’s lignite plants give off massive amounts of CO2, but a carbon price looks unlikely (Photo by Harald Hillemanns, edited, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A new study by Energy Brainpool (PDF in German) comes to an unsurprising finding: Europe’s carbon emissions trading scheme (EU-ETS) has no effect on shares of gas, hard coal, and lignite in Germany. The price of carbon continues to flail along below 10 euros per ton of CO2; it’s closer to seven euros at present and even fell below four euros in 2016.

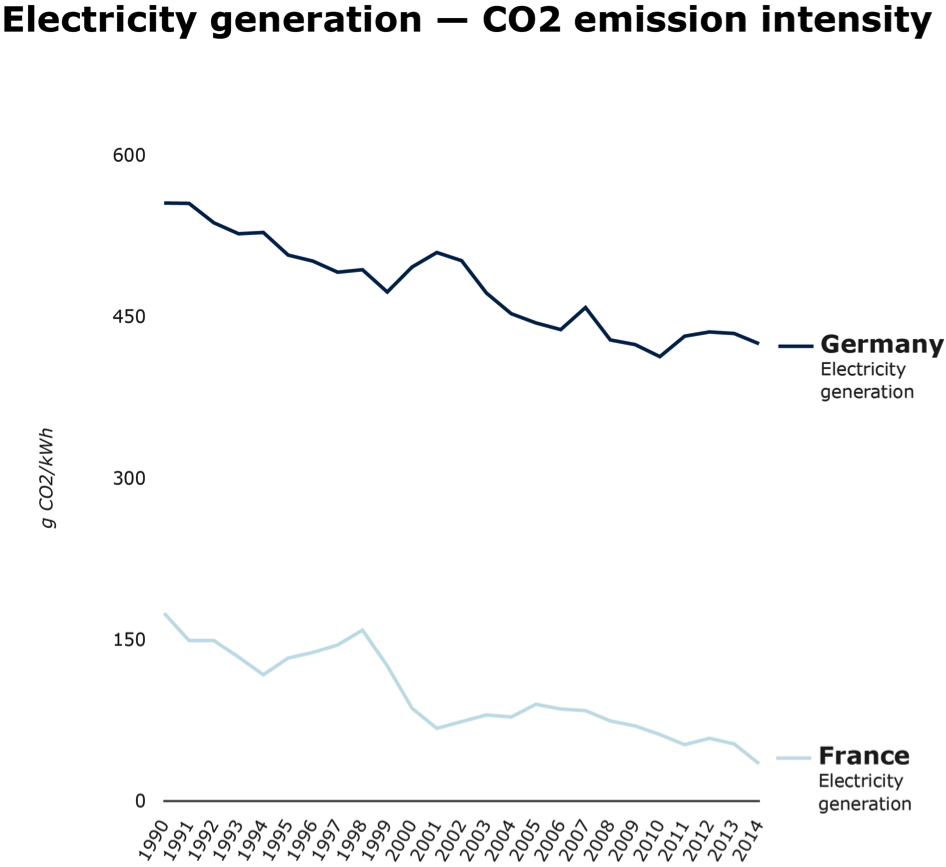

French President Macron has now called for the price to be set at a minimum of 25-30 euros. France has long been a supporter of higher carbon prices, but the German government remains lukewarm about such ideas, which would make France more competitive relative to Germany due to the high share of low-carbon nuclear power in France (around 75%) and the high share of coal power in Germany (around 40%).

In recent years, the carbon intensity of German power has been roughly ten times greater than France’s, partly because the French are clamping down on the already small share of coal power. However, the French have had a plan for a minimum carbon price for some time now; unlike the UK, they simply refuse to implement one unilaterally – in particular, they want Germany in.

Source: EEA

Macron’s idea is thus unlikely to meet with more approval in Berlin than his many other ideas about stronger Franco-German cooperation – but let’s wait to see what coalition Merkel brings about.

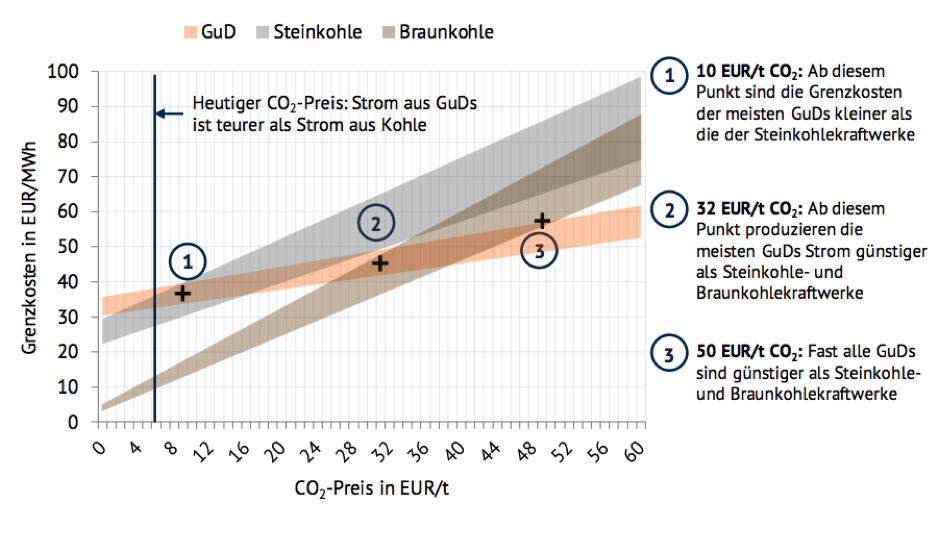

Energy Brainpool identifies the following price signals:

- Below 10 euros per ton of CO2, the price of carbon has no fuel-switching effect on power markets in Germany, meaning that none of the fuels (gas, hard coal, and lignite) start to shift market shares.

- At 10 euros per ton of CO2, combined-cycle gas turbines (CCGTs) start to become competitive with hard coal plants.

- At 32 euros, CCGTs start to be competitive even with lignite plants.

- At 50 euros, practically all CCGTs are cheaper than all coal plants, hard coal or lignite.

GuD stands for CCGT, Steinkohle = hard coal, and Braunkohle = lignite. The marginal price of lignite in Germany – a domestic resource – is dirt cheap. At Macron’s lower proposal of 25 euros, lignite just starts to be replaced by natural gas in CCGTs. Source: Energy Brainpool

These findings are, for what it’s worth, nothing new. Germany’s Öko-Institut came to similar conclusions years ago in a paper for the WWF (PDF in Germany). For that matter, so did Energy Brainpool in 2013 (PDF in German). Back then, the price where CCGT would replace all coal was estimated at 55 euros.

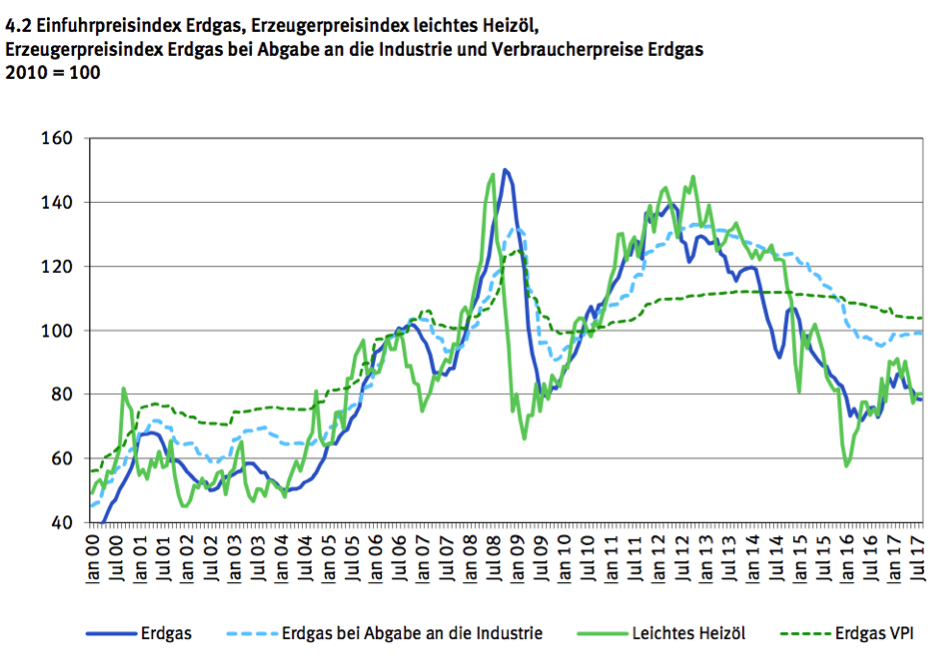

It thus seems that the necessary carbon price remains fairly stable even though the price of gas imported to Germany nearly fell by half from 2013 until today, according to the latest data from the German Statistics Office. Note that the chart below is an index (100 = 2010).

The price of light heating oil (solid green line) and natural gas (all other lines) imports is quite low at present but still not competitive with German lignite. Source: German Office of Statisticss

At the same time, the German Office of Statistics shows that the price of hard coal imports is slightly rising. The price of gas thus cannot realistically fall low enough to replace domestic lignite in Germany, and the shift in prices for natural gas and hard coal imports (Germany will close its last hard coal mine next year) is not enough for a fuel switch either. In other words, the market will not take care of this by itself. We need a carbon price.

If the Jamaica coalition of the CDU, FDP, and Greens comes about in Germany, it is unlikely that the new German government will play along with Macron towards a minimum price, however. The Greens have long called for one and continue to do so (in German). The CDU opposes the idea (in German): “The ETS is a tool to control the volume of emissions, not to control prices,” a leading CDU member states in August. As for the FDP, its opposition to a floor price for carbon was prominent in the election campaign (in German).

In all likelihood, Germany will continue to oppose a minimum carbon price, preferring a market failure – the current ETS – to any “governmental intervention.”

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

The ETS isn’t a market failure but a policy one. History shows that it needs a minimum price to work.

At some point Macron may just introduce one in France, hoping to start a movement that will isolate Germany and Poland.