Lithuania is a net energy importer, and many in the country are worried about security, especially because of their reliance on Russian gas. Nuclear is not an option – the government needs to invest in renewables if they want to improve their energy system, says Monika Kokstaite.

Wind power plant under construction near Vilkyčiai, Lithuania (Photo by Kusurija, edited, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Lithuania is one of the smallest energy consumers in the Baltic region and the EU, and it represents one of the most complex examples of energy security problems in the region.

Lithuania has been struggling with its external energy dependency since 1990. It was the first country to receive imported gas from Russia (at that time, the USSR) back in the 1960s. Currently, imports from Russia still make up a high share of the Lithuanian gas market.

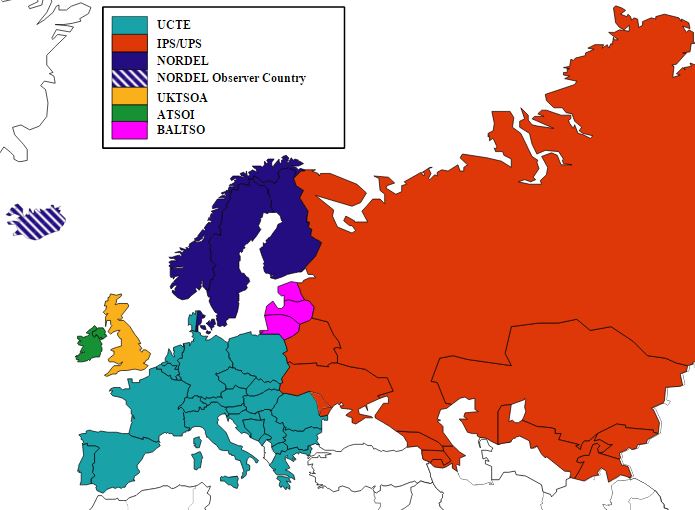

As for the electricity sector: the BRELL (Belarus, Russia, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) electricity ring, part of integrated larger IPS/UPS synchronized zone, has been meeting the domestic electricity demands for almost five decades. Designed under Soviet regime and centrally controlled by Moscow, the system is now perceived as a great risk to Lithuania’s energy security.

European energy systems: the IPS/UPS zone is pictured in red (Photo via Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Although the Lithuanian government has been examining other interconnection options with continental Europe since 1998, various feasibility studies show that the envisioned energy system transfer (the import/export of both gas and electricity from the EU countries or energy interconnections) will not take place till 2025. Thus, the physical isolation of Lithuanian energy market continues to be an issue.

However, there has been some progress in developing new interconnections in the recent years. The grid-extension projects linking Lithuania with Poland and Sweden were finalised in 2016, transporting Nordic electricity. Moreover, the LNG terminal and floating storage in 2014 opened the doors to Nordic gas. Meanwhile, market liberalisation has been progressing at a full speed. The unbundling of generation from transmission activities in the gas and electricity sectors in 2013 made both markets compatible with EU norms.

At the same time, the closure of the Ignalina’s nuclear power plant exacerbated dependency on Russia and energy security issues. In 2012, Lithuania imported almost all of its annual gas demand (~2,4bcm) and 63% of its total electricity needs from Russia. Before 2009, Ignalina’s nuclear power plant met 77 % of the country´s electricity needs, while 58 % of its total output was exported to other countries. However, after the plant closed, Lithuania turned from an exporter to an importer of electricity – 2/3 of the country´s electricity is imported.

Low levels of energy efficiency, low income, the lack of competitiveness, and no long-term strategy for the domestic energy sector posed a significant threat to the state’s energy security. The first long-term energy plan was the 2012 National Energy Independence Strategy, which incorporated EU’s 2020 energy and climate goals. Renewable resources and nuclear energy were seen as a way to reduce excessive imports and heavy reliance on Russian gas, paving the way to a fossil fuel free Lithuania by 2050.

However, the referendum on the nuclear power plant that was planned to be built in October 2012 sent the project to oblivion by population’s negative vote, casting a shadow on country’s capacity and ability to reach its goals by 2020. Due to the national parliamentary elections in October 2016, the new National Energy Strategy has been delayed since September 2016, which makes it even more unclear how the country is going to reach the targets on time and ensure energy security. As the country with the highest energy poverty in the EU, Lithuania’s priority remains affordable energy, reducing energy intensity and cutting its domestic energy bill. Meanwhile, one third of the population cannot afford to keep their homes sufficiently heated.

The closure of the old nuclear power plant and the vote against a new one paved the way for the development of renewable energy sources (RES). Comprising barely 15% of the total energy consumption in 2009, RES increased by one fifth in the following 5 years.

Biomass (86.5 %) and biofuel (4.4 %) represent the biggest share of RES, whereas hydropower and wind energy, account each for 3.9% of the total distribution. Solar power, unfortunately, has limited potential due to the geographic conditions. Wind energy continues to be the most sustainable RES compared to the environmental impact of biomass. However, the government’s plans to increase the existing wind power capacity by 50 % could not be realised without support mechanisms or other incentives. Opinion polls show that more than 80 % of Lithuanians support RES energy and the majority is also willing to pay more for green energy. With a new coalition of Peasant and Green parties, Lithuania could finally opt for the long awaited real solutions to ensure energy security and sustainability in the country.

To conclude, Lithuania’s self-sufficiency continues to be a political priority, but without a clear vision on how to achieve it, the huge imports of gas and electricity will not be replaced. The list of suppliers expanded, but the import itself did not shrink much. The government’s reluctance to support the expansion of wind and solar power is partly due to the lack of financial means. The increasing energy consumption is expected to pose more challenges, as the country’s future energy system remains unclear. However, the reduction of administrative and grid-related barriers, combined with a stable and predictable regulatory framework that attracts investments, could play a significant role in Lithuania’s energy transition.

Monika Kokstaite is a PhD Researcher at IMT LUCCA (Italy) and Senior Consultant-Project Manager at everis, NTT DATA Company (Brussels office). She has been working with energy issues since 2008 in various EU countries, analysing renewable resources, energy policies, efficiency and technology.

The future of the whole Europe is currently at a crossroads since Ukraine has offered its territories to store the US nuclear wastes:

https://topbuzz.com/@olsundberg/america-to-bury-even-more-nuclear-waste-in-europe-CgJAixPv0Vk

[…] and Ukraine, Russia inevitably stepped in to fill the supply gap. By 2012, Russia was providing 63% of Lithuania’s electricity and Gazprom became the sole supplier to Lithuania’s natural gas […]