Germany has held its first auctions for onshore wind farms, and the projects that fit the brand-new definition of “citizen wind power” got almost all of the volume. So why do most people seem so unhappy? Craig Morris investigates.

‘Citizen cooperatives’ may be front organizations for private-sector developers who want special treatment (Public Domain)

Rainer Baake’s job isn’t an easy one. Last year, the German Energiewende Undersecretary told the audience at the annual conference of German energy cooperatives (DGRV) that they would have to take part in onshore wind auctions like everyone else starting this year. The cooperatives wanted to be able to participate as “non-competitive bidders,” meaning that they could go ahead with their projects at whatever price was determined in the auction. Baake rejected the proposal.

But the cooperatives did not give up, and early this year Baake’s ministry announced a compromise (report in German) – one that included a new definition of citizen wind projects:

- At least 10 citizens must be involved, none of whom own up more than 10% of the project.

- The citizens must, however, owned at least half of the shares.

- And at least half of the citizens must live in the county where the wind farm will be built.

In return, the citizen projects do not need an environmental impact assessment (EIA, or BImSchV permit in German) to participate in the auctions. An EIA can be quite expensive and is by no means a foregone conclusion.

In addition to the risk of not getting the permit, citizen projects feared that their bids might not win, leaving them sitting on six-figure losses. It is generally assumed that bigger companies will participate in multiple rounds of auctions and probably make several bids in each round, so economic losses from losing bids can be spread around. In contrast, the prospect of losing everything in a bid might scare citizens away from the outset, and once they have lost they might never participate again.

In March, Germany’s Network Agency (the grid regulator that conducts the auctions) announced what seemed to be a success for citizen wind power (press release in German). Prices were very low at 5.58-5.78 cents, and citizen projects got almost the entire volume. And then the complaining began.

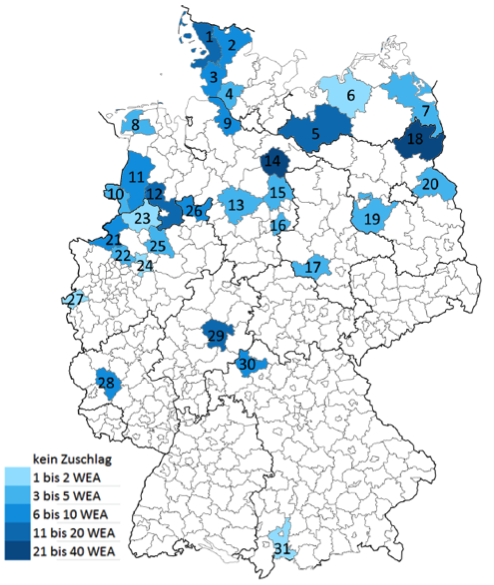

Winning bids were concentrated mainly in the North in Germany’s first round of onshore wind auctions – even though lots of bids came from the areas in white. The numbers show how many turbines are to be built (WEA = wind turbine). Source: Deutsche Windguard.

First, there were nonetheless a lot of losers. Out of 2,137 MW submitted, only 807 MW can be built. There were 256 bids, 71% of which were citizen projects in terms of volume. 65 citizen projects can proceed, but around 100 lost – along with almost all private-sector bidders.

Then, there are the long timeframes: the citizen projects have a whopping 54 months – 4 ½ years – to complete their wind farms, instead of only 30 months. (Wind farms can usually be built within 24 months.) It is likely that none of these citizen projects will be built quickly, so the German onshore wind market could dry up from 2018-2020. Furthermore, 95% of the citizen projects still lacked an EIA, which the winners now have to produce – and that could fail.

Finally, the definition of “citizen projects” met with criticism from the outset – these are not proper cooperatives. When the results were announced, Rene Mono of the Citizen Energy Alliance called for an investigation into whether “all of the companies that complied with the definition of citizen projects have what is needed for community energy: democracy, codetermination, and input from local people” (report in German). In cooperatives, each member has a single vote regardless of how many shares they hold.

German economics daily Handelsblatt then investigated the matter (in German behind a pay wall) and found evidence that the local citizens in many of the projects seem to be employees of the companies. In other words, a lot of the citizen projects seem to be front organizations for private-sector developers who wanted to benefit from the special treatment for citizens. German wind energy organization BWE wanted to have the minimum number of citizens increased to 50 to prevent such abuse, but their proposal was not adopted (report in German).

In the end, we have some amazing headlines: record low prices, and it’s citizen energy! But the reality could be sobering. Unless the legal framework is changed, the business world has to cobble together some citizen lackeys if they want to win bids. And in the next few years, feed-in tariffs will expire for large volumes of wind capacity built 20 years ago. It’s possible that the amount added in the next few years will be smaller than the amount dismantled. The German wind power sector will then be treading water. And Baake, who is bathing in sunlight now, might face stark criticism again.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

At an auction price of 5.58 c€/kwh, the cooperatives should consider just going it alone. Find a customer, sign a conditional PPA, get the EIA, and build. The return will be a little less, but there’s less project risk than in squeezing through the narrow auction window defined by bureaucrats in Berlin. This presumes that there are well-informed PPA intermediaries who will broker deals.

Some 60 GW are already in “Direktvermarktung” , that is about 2/3 of the RE-power capacity traded on the market.

[…] second auction was a repeat of the rules from the first, and the complaints are similar. According to the Network Agency’s press release (in German), […]