By 2020, Germany aims to get 35% of its power demand from renewables, but the share was much higher in the first half of this year. But there’s also some bad news. Craig Morris explains.

Wind and solar have made great strides – but new policy may stop them cold (Public Domain).

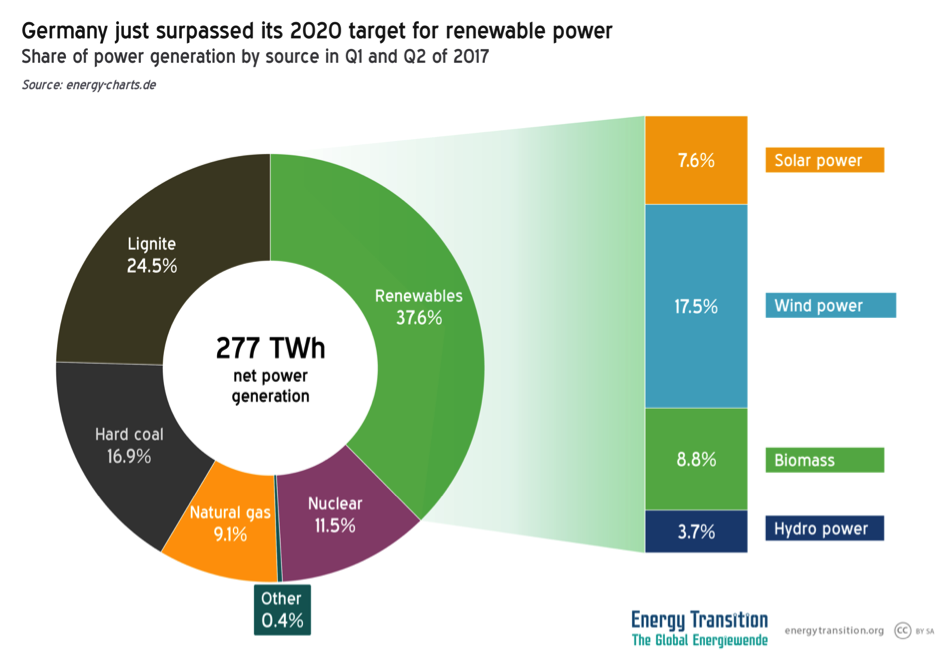

At the beginning of July, Fraunhofer ISE’s website showed that Germany had 37.6% renewable power in the first half of the year – far above the goal of 35%.

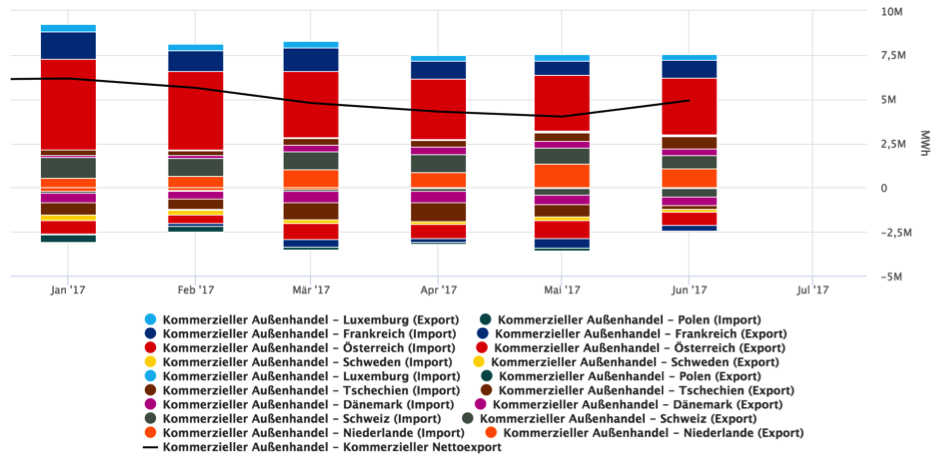

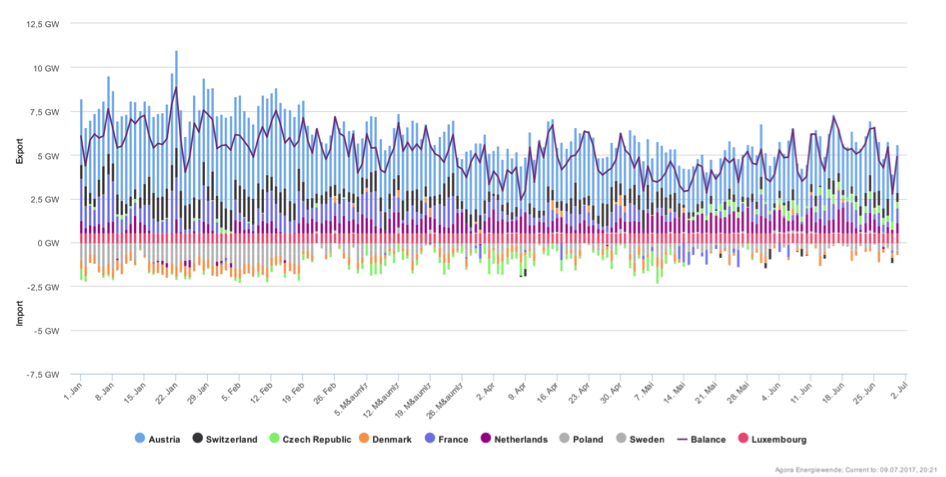

The share of renewables is even larger when we consider power demand, i.e. take out net power exports; the chart above shows generation, not just demand – and Germany became Europe’s leading power exporter last year. To explain this, I’d like to introduce you to a new platform currently only online in German: Smard. Like the Agorameter, it shows net commercial power trading. Germany exported 29.8 TWh net, equivalent to 11 percent of total generation, which we can subtract from the total above for all power generation including exports. Renewables then made up 42% of power demand in Germany.

The Network Agency’s new Smard website is pretty powerful (if you can navigate the German) but could use some tweaking for readability. Here, the bars above the baseline show power exports by country; those below the baseline, power imports. The black line is the net result, which varied from a high of 6.2 TWh in January to a low of 4.0 TWh in May. (Source: Smard.)

These figures are still preliminary, but any adjustments are unlikely to be great. The biggest variable is the weather. The first half of 2017 was both fairly sunny and windy. But it will be hard to drag the share of renewables back down below 35%.

The Agorameter also shows commercial power trading and is available in English. Unlike Smard, it does not let you access raw data. Here, we see that Germany was a net power exporter (line) every day of 2017 up to now. (Source: Agora Energiewende)

Solar continues to creep upwards, but the main growth has come from wind power. In the first half of 2016, solar and wind collectively generated 58 TWh, but that figure rose to 68 TWh in the first two quarters of this year. Wind power made up most of that 10 TWh increase at 7.5 TWh.

One reason has been the recent record expansion of wind farms. In the past few years, wind projects have rushed to finish before auctions take effect. Under auctions, the government will be able to decide which projects can be built; effectively, the government can tell developers they cannot build simply by keeping the volume auctioned at a modest level. (The first round of onshore wind auctions was more than 1.5-fold oversubscribed, meaning that there were 1.5 losers for every winner.) Under feed-in tariffs, the government had no way of stopping projects based on volume. The result was more than 4 GW of capacity additions annually for the past three years after a decade of closer to 2 GW each year.

In contrast, large PV arrays (the size limit is now 750 kW) have had to take part in auctions for the past two years. Since then, new builds have failed to meet the government’s minimum target of 1.5 GW annually.

So what will the share be by 2020? It might not be much higher at all. A lot of wind turbines will leave the feed-in tariff scheme in the next few years after 20 years of eligibility. Those wind farms could theoretically still sell power at the wholesale rate, but that price might be lower than operating costs, especially if any maintenance is needed for the old turbines. Many machines will thus be dismantled.

In addition to this reduction, which will be significant for the first time (not much had been built more than 20 years ago), the auctions also allow projects several years to develop: from 30 to 54 months. The volume awarded this year – already relatively small at 2.8 GW (source in German) – is thus unlikely to be built in 2018 or 2019. Most projects from the first round have until 2022.

So whatever share of renewables Germany has for 2017 as a whole will probably be close to the percentage it will have in 2020. The good news is that the target for that year will probably be reached. The bad news is that solar continues to be developed at a meagre pace, and now the wind sector is bracing for an extended dry spell.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

I would think that the existing concrete base structures, grid and vehicle access, and neighborhood acceptance would have considerable value for repowering with modern generators, even though they might be limited to smaller sizes than one (but not probably not the neighbors) would otherwise prefer. Maybe there need to be some business models for doing this on a significant scale via the auctions.

New generators are bigger, catch more wind and therefore the physical load on the foundations is different.

“So whatever share of renewables Germany has for 2017 as a whole will probably be close to the percentage it will have in 2020.”

That is at least debatabel: According to DEWI and others, around 9 GW windpower are approved for 2017/18, therefore, we will have 10 GW more in 2020 than in 2017.

This means we will see around 25 TWh more RE generation in 2020 than in 2017 with the same average wind speed, i.e. around 4% higher RE share.

“Those wind farms could theoretically still sell power at the wholesale rate, but that price might be lower than operating costs, especially if any maintenance is needed for the old turbines. ”

Well, I thought that the operating cost was extremely low for wind, If expensive maintance (=major repair) is needed then I understand that the wind turbine will be dismanteled. Or if possible on the site in question, repowering with a much more efficient modern and larger(?) wind turbine. Could you please elaborate on this subject?

Request for data seconded. At first sight, it doesn’t look plausible. The German day-ahead wholesale price oscillates round about €30/mwh; that should be plenty to keep a fully amortised old turbine operational. The phaseout of the remaining nuclear plants, combined with the modernisation of the surviving coal fleet, will reduce the number of hours when must-run capacity drives the wholesale price into negative territory.

In fact, it seems more likely that at an average price of €30/mwh, and with some further technical progress, it will be possible to build new wind farms outside the auctions entirely, for sale into PPAs with large customers like steel mills or on a merchant basis. This is beginning to happen in the UK.

Correct, the new off-shore ‘subsidy-free’ wind generators plan to operate within the free market.

The on-shore generators have considerable lower maintenance and construction costs and a much wider acess window.Their sites are probably in high demand by developers.

One of the reasons why the old on-shore generators could see a certain amount of decomissioning after the FIT runs out is the availability of spare parts, they were build in much smaller quantities, mass production wasn’t that common 20 years ago and many manufacturers gave up.

Some building permits were only for temporary usage for 20 years or so. However the communities got used to the income and would be more than pleased to keep it flowing.

“The German day-ahead wholesale price oscillates round about €30/mwh; that should be plenty to keep a fully amortised old turbine operational.”

Enercon gets IIRC 1-2 cents/kWh for full service contracts, and they are expensive. They also sell their latest turbines with a 30 year production life, this only makes sense if the wholesale price covers service costs and still gives income for the owner. 🙂

In addition, almost everybody expects HIGHER wholesale prices after 2021 when more than 10 GW baseload will be retired.

Re. power futures:

these are falling in the German market resp. staying at the level we are used to. Despite the atomic exit and the new coal emission legislations( http://www.euractiv.com/section/air-pollution/news/dawn-of-new-eu-rules-could-sound-death-knell-for-coal-power/):

https://www.eex.com/en/market-data/power/futures/phelix-deat-futures#!/2017/08/08

The French futures however are bullish,France closes atom power plants ahead of building enough RE-capacities firstto compensate. At least this is the official statement from the government and the speculaters act accordingly:

https://www.eex.com/de/marktdaten/strom/futures/french-futures#!/2017/08/08

But for the German market there is hardly any interest shown by traders in the long term futures, the pricing is still to high to complete deals. Most buyers seem to speculate on further price drops, the traders simply get no orders for 4-5 years ahead.

RE-capacities are faster installed than the futures reach (year 2023), if future prices rise unexpectedly a very quick RE-installation would be the response.

Material is available, the technology is understood and with a demand (contract) the financing is no problem.

After the summer break of the German parliament the standardisation of Plug-and-Play PV installations will be put into the legal dry.

Meaning everyone will be allowed to buy and connect a PV-installation into the next household socketin a couple of weeks,limited up to 0.6KW per circuit/fuse board fuse I think.

This will cause a major boom in the number of small installations, a voter’s and maket force that can’t be ignored.

Since these guerilla installations are not limited by auctions or FITs this will allow – in theory – for a 100%+ PV covering of the German electricity demand in due time.

40 million households/individual meters with an average of 8 circuits on the fuse board multiplied with 0.6 kW allows for 3.6 KW per household. Plus the existing PV-installations of 40 GW results in a double or triple overcapacity of the max. recorded German peak demand at noon.Roughly.

This German regulation will be the blue print for the long awaited EU standardisation for plug-and-play/guerilla PV, the new EN standard for grid connected small scale generators.

If anyone familiar with the issue would pick-up these calculations please do so, thanks.

In the mean time the oil producers are throwing out what they can.

About the “SMARD” data collection:

An English version would be fine, similar to Fraunhofer ISE.

Between now and 2022 that 11.5% of nuclear will be phased out, offsetting any growth in wind and solar. Only once that has been achieved will carbon emissions start to fall further. Also, we have the rest of the German economy that is not significantly reducing fossil fuel usage. The result is that slow-growth Germany is making little read headway on reducing carbon emissions, and won’t until at least 2022. That should be the real headline, rather than the feel good one.

http://www.euractiv.com/section/air-pollution/news/dawn-of-new-eu-rules-could-sound-death-knell-for-coal-power/

Germany’s old bangers are making no profit no more and the new ones are to expensive:

https://www.platts.com/latest-news/coal/london/german-coal-margins-for-oldest-power-plants-turn-26784077

There is no major price change expected for electricity for many years ahead:

https://www.eex.com/en/market-data/power/futures/phelix-deat-futures#!/2017/08/08

If the CO2-emmission price increases most coal power plants and many gas power plants as well will close.Plus the closures for the linked reasons …

The average RE-part in the public grid has surpassed 40% for the time frame week 6/2017 to week 32/2017

https://energy-charts.de/ren_share.htm