How big can a community project be? How does 93 turbines and 400 million euros sound? The latest onshore wind farm going up in the Netherlands will be more than 50% larger than the biggest one now standing – and it may be just the beginning. Why is Dutch community wind so utility-scale? Craig Morris investigates.

Zeewolde: a hugely successful, community-owned wind farm (Photo by Floris Oosterveld, edited, CC BY 2.0)

Literally formed out of land reclaimed a half century ago from Ijsselmeer, the giant lake in northwest Netherlands, the province of Flevoland is largely farmland – and the center of Dutch onshore wind power production.

The new Dutch campaign’s ad reads, “We are doing it for her, too.” (Source: Windunie.nl)

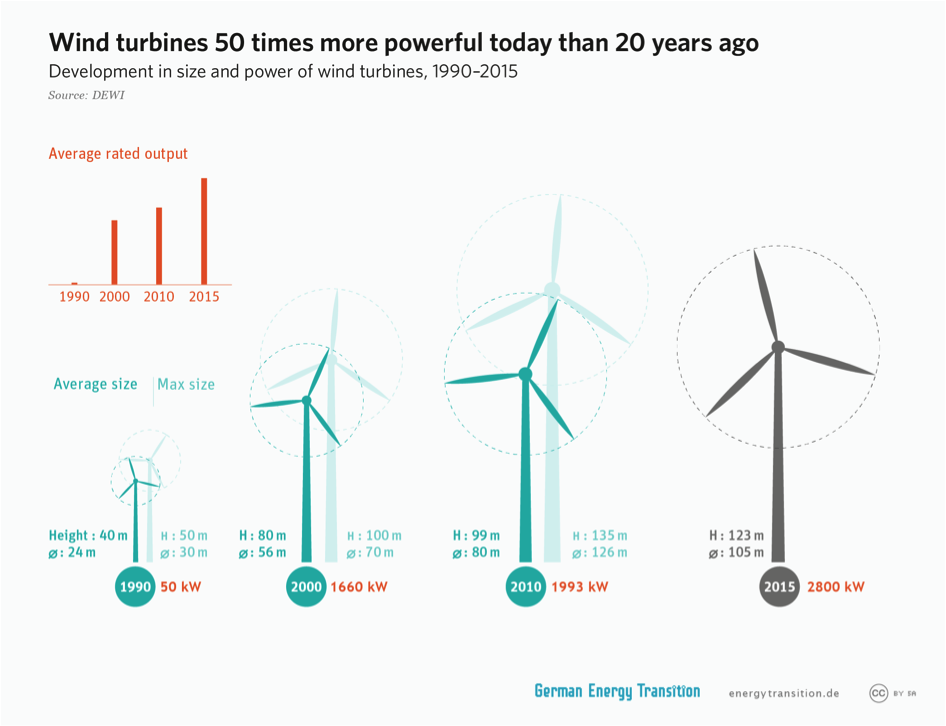

Hundreds of turbines there are nearing the end of their 20-year service life. Replacing them – a process called repowering – is not a one-to-one proposition because wind turbines have grown so much in the past few decades.

One question I am often asked when presenting the success of German community projects in the wind sector is whether projects haven’t simply gotten too big for small players. In light of the growth of turbines, the question seems logical.

The Zeewolde wind farm provides a clear answer. Roughly 200 local citizens, many of them farmers, and owners of the old wind turbines realized around a decade ago that they would soon need to start planning for the end of their wind turbines. “There was some bad blood from those days,” says Siward Zomer, head of Dutch wind cooperative De Nieuwe Molenaars (the New Windmillers). “Some landowners were making 30,000 a year because the turbines were on their land,” he explains, “but their neighbors, who basically lived just as close to the turbines, got nothing.”

At the behest of the European Commission, most European countries are now switching to auctions, a system in which bidders compete with each other. But to overcome the inequities of the current situation, “the municipal and provincial governments made everyone collaborate.”

The result was a five-year-long discussion in which citizens had to answer questions like: how much money should a landowner get if a cable runs over their property? how much do you get when a wind turbine is on your land and how much does your neighbor get? Normally, the terms are negotiated with the project developer. Now, these conditions were set by the democratically organized wind organization set up by the citizens themselves. The government then would only continue with the planning permits if the public accepted the outcome – not after some fluke referendum or election based on empty promises, but after informed, lengthy negotiations between citizens. “It wasn’t easy,” Zomer sums up the experience.

The citizens who owned a wind turbine or had property in the area used to be members of the wind organization, but citizens living in nearby villages were left out. REScoop.nl and REScoop.eu (the Dutch and European federation of citizen energy cooperatives) therefore put capital together to buy an existing wind turbine in the area and set up a local REScoop for citizens in the villages to own. This local REScoop would get the same rights to participate in the new wind farm. “We were short some 40,000 euros at one point,” Zomer remembers, “so we worked with REScoop.eu to find international citizen investors.” REScoop connected the Dutch with Spanish citizens, out of solidarity and cooperation with their northern citizens.

In the end, some 80 million euros in equity needs to be collected to leverage 320 million euros in bank loans to cover the full price tag of 400 million euros. Daan Creupelandt, spokesperson for REScoop.eu, says his organization is currently working on a revolving fund as part of the REScoop MECISE project to make it more convenient for local co-ops to make international investments. For the full potential of such citizen projects, see this.

Ten million euros of the project will be on offer as bonds for public purchase. The price of a single share, the smallest amount procurable, is a mere 250 euros, thereby allowing a wide range of income levels to participate. “Locals get to buy first,” according to Zomer, “but others can also get on board if not all the shares are sold locally.” In the end, some 200 locals farmers and owners of the old turbines will join forces with an expected 1,000 citizens to finance the gigantic project.

If all goes well, it could lead to subsequent projects. After all, other old turbines will be coming up for repowering soon. “We could have a revolving fund,” Zomer hopes. “New coops that lack money could join forces with old coops looking for new projects.” He puts the potential for community wind repowering at “1,000 MW”; to put this into perspective, only 4,328 MW had been installed in the country by the end of 2016 (PDF).

Perspective may also be useful for the project’s size. At 350 MW, it is twice as large as any single project in Germany (list in German). The largest onshore wind farm in Europe is a 600 MW project in Romania built by the CEZ Group from the Czech Republic in 2012.

What’s more, the discussion and ownership options are making wind power more popular in the Netherlands. In other countries, you might expect protesters to appear during the information events in the planning stage, but Zomer says “we increasingly have people coming by to have look at their wind farm.”

If you speak Dutch, you can learn more here about the Nieuwe Molenaars. The Zeewolde wind farm should be finished in 2019.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

I’ve been sceptical in the past about Craig’s enthusiasm for community wind, but this piece provide solid evidence for a rethink on my part – and more important, by others. Solving the distribution issue fairly is a major plus. It’s still a very large investment to ask the locals to make (it must be a big share of their assets), but focussing on re-powering lowers the risk because the wind conditions are known precisely from the old turbines.

Really interesting and important. In general I worry with such projects (for example if one tried to do something like this in the US) about upper limits on the risk, since one is often at the mercy of larger forces.

[…] artikel is eerder verschenen op Energytransition en met toestemming van de auteur vertaald door Krispijn […]

[…] the recent Community Energy Congress. Community ownership isn’t limited to size, either – the biggest planned wind farm in the Netherlands is set to be partly community […]

[…] such as the Community Energy Congress. Community ownership isn’t limited to size, either – the biggest planned windfarm in the Netherlands is set to be partly community […]

[…] their “polder mentality” – their community can-do spirit. In 2017, it led to a gigantic citizen-owned wind farm: 93 turbines worth 400 million euros. “The government basically insisted that farmers get […]