A recent study contracted by the German Greens finds that Germany stands little chance of reaching its 40 percent target for carbon emission reductions by 2020. But if you think coal power is the big issue, you might be surprised to hear what Craig Morris has to say.

Emissions stay high – but coal might not be the culprit (Photo by Leon Liesener, edited, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Call it hubris – or maybe just basic unrealism: back in 2007, Chancellor Merkel and then-Environmental Minister Gabriel adopted an ambitious target to reduce carbon emissions by 40 percent by 2020. How unrealistic was it?

First, consider that the original nuclear phaseout of 2002 (revised in 2010 and then summarily readopted in 2011) would have seen the closure of most nuclear plants in Germany by 2020. The removal of that low-carbon power would only make it harder to lower carbon emissions during those years.

What’s more, in 2007 we didn’t know that renewables would grow so fast. From 2000 to 2006, the share of green power grew from 6.6 percent to 11.2 percent, an increase of less than one percentage point per year. Since 2006, that share has grown twice as fast, but this success was not certain in 2007.

And then there was the rate of emissions reductions. By 2012, German needed to reach a 21 percent reduction for Kyoto, leaving eight years for another 19 percent – roughly 2.4 percentage points annually. To put this number into context, an 80 percent reduction is the goal by 2050; measured from 2012, that’s 1.55 percent annually. So the short term goal is 50% more ambitious than the long-term one – despite the simultaneous nuclear phaseout!

There is one mitigating factor: Germany actually reduced emissions by close to 25 percent by 2012, far surpassing its Kyoto target, so Germany only needs to lower its emissions by 15 percentage points by 2020. But still, 15 percent in eight years is fast – a third faster than the long-term average.

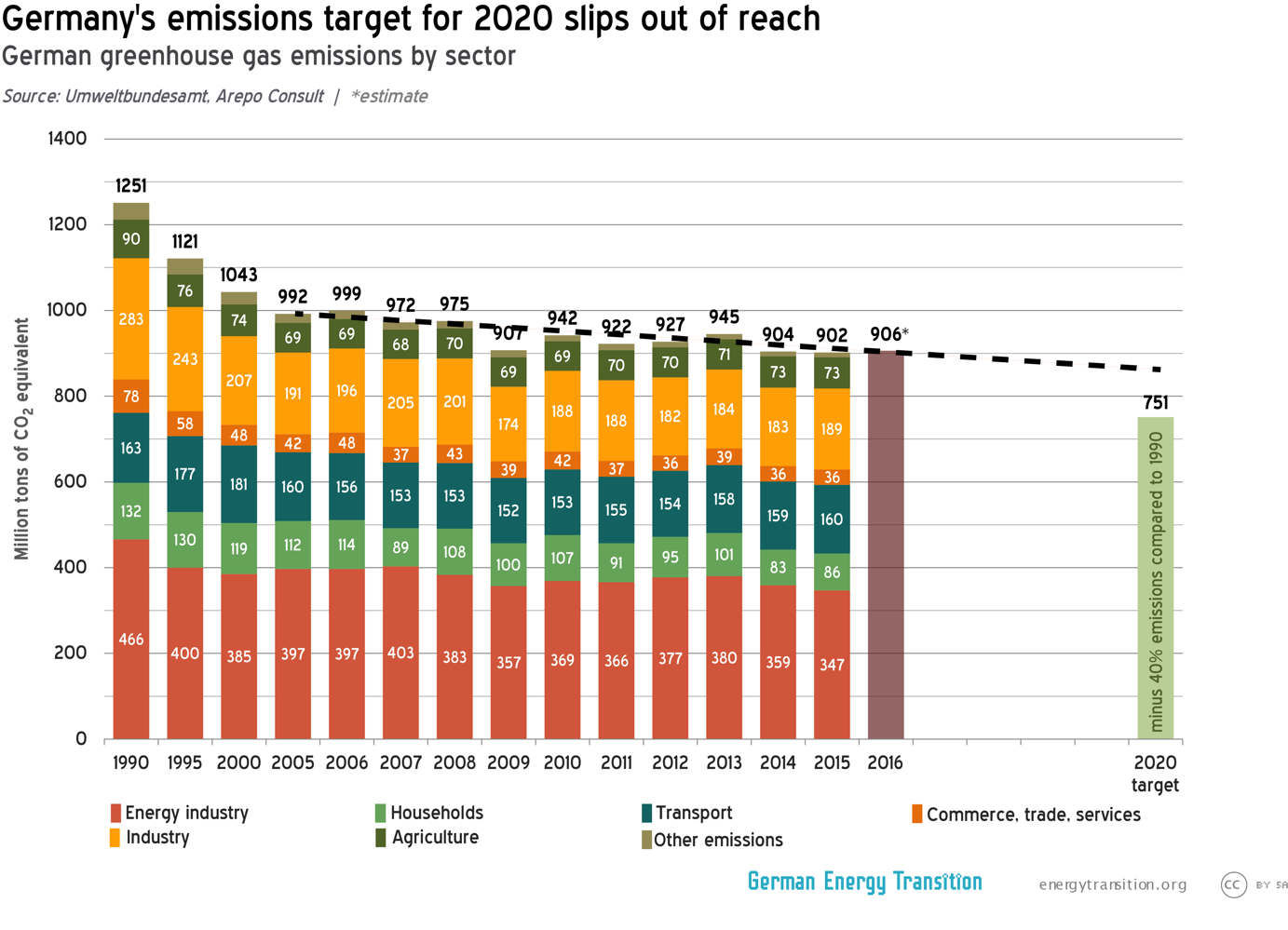

Based on the nuclear phaseout and the nascent state of renewables in 2007, it would certainly seem like the period from 2012-2020 would be a time to expect lower-than-average carbon reduction. Perhaps Merkel and Gabriel thought some low-hanging fruit would ensure success nonetheless. Whatever the case, in a paper for the Greens (PDF in German) Arepo Consult estimates that German carbon emissions were up by around 0.5 percent in 2016.

The hard data for 2016 are not yet available, but in January German environmental agency UBA announced the numbers for 2015. A mere 0.3 drop had brought the total reduction to 27.9 percent. Germany now has five years to shrink by another 12.1 percent – 2.4 percent per year. Since 2012, emissions have dropped by only around 0.5 percent annually. At that rate, Germany will be closer to 32 percent than 40 percent.

Coal maybe not even biggest problem

Keep in mind that emissions from coal power are down. Both the UBA (PDF press release from March 20) and Arepo point out that emissions from transport and heat are the problem. The level of emissions from buildings is practically the same as in 1995; from transport, since 1990. Clearly, too little progress is being made in heat and transport; Germany’s energy transition remains an electricity transition.

Refugees also increased the population of Germany by around one percent in 2016. Many of them were temporarily housed in large uninsulated tents with hot air blown in – a very inefficient process. This effect may remain temporary, however.

But that impact only adds to a structural problem: Germany has not yet figured out how to ramp up the rate of energy-efficient building renovations. And Berlin spent the past decade defending diesel rather than electric mobility, including public transportation – not to mention bike lines and walkable cities.

The authors from Arepo have clear recommendations: close coal plants and switch to hybrid and electric mobility, including railways. For the heat sector, they recommend “greater efficiency.” But how? Calls to force homeowners to insulate properly and replace old oil-fired heating systems with efficient new ones (ideally running on gas or renewable heat) meet with charges of expropriation. Merkel opposes a quick coal phaseout because of the impact on the communities affected (report in German). And municipal governments in charge of building bike lanes and improving public transport lack funding.

We all know what the problems are. We even have a lot of solutions. Getting them implemented – that’s the crux. To do so, we need social, not just technical solutions. The German public, which allegedly supports the Energiewende strongly, has to be convinced to start taking the right steps outside the power sector.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

In the UK, the Government has allowed new properties to be built, which are below Northern European energy efficiency standards. Old council (social) housing estates, have needlessly demolished to make way for energy-inefficient ‘homes-to-buy’. Even with all this re-generation(?), very few district heating systems have been incorporated into the new developments.

The UK’s transport system is geared up for private motor vehicles. With public transport being privatised, it has suffered a haemorrhaging of services for the public. The rail system still runs on a mixture of different electrical systems and diesel. Walking and cycling in Cities is a hazardous undertaking, putting most people off, even trying. And the air quality in the UK, most be some of the worst in Europe, despite the loss of heavy industry.

I think in Germany, the public support social change, something that is lacking in the UK, even in the Green Party.

Maybe targets should also be reviewed in absolute terms. For example, according to German UBA (http://www.umweltbundesamt.de/themen/klima-energie/energieversorgung/strom-waermeversorgung-in-zahlen?sprungmarke=Strommix), their electricity generation for 2015 is 535 grams CO2 emitted/kilo-watt hour (according to International Energy Agency, France is about 70, Sweden 12 and Switzerland 28). The IEA states, in order to reach Paris climate change targets, this number needs to be below 100.

Also, reviewing IEA’s tonnes CO2 emissions/capita (2014 data, page 115 https://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/co2-emissions-from-fuel-combustion-highlights-2016.html) , Germany is 8.93, France is 4.32, Sweden is 3.86 and Switzerland is 4.61.

I would suggest not only is it much more critical that Germany hit their CO2 emission targets compared to the other three countries, but perhaps a case could be made that Germany’s targets need to be much more aggressive.

[…] we talked about the fact that Germany’s energy transition has been too electricity-focused. Today, John Grant describes what is necessary for more efficient buildings: the support and […]

[…] artikel is eerder verschenen op Energytransition en is met toestemming van de auteur vertaald door Krispijn […]

[…] Germany to miss 2020 carbon reduction targets by a mile […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]

[…] in nuclear power consumption, Germany has been unable to reduce fossil fuel consumption as much as previously hoped. This shortfall is especially the case with natural gas, which has been a central cause for concern […]